I always been very open about the incredible amount of professional respect I have for my science collages at the Oceanic Fisheries Programme of SPC, they are regional centre for tuna fisheries research, fishery monitoring, stock assessment and data management.

Perhaps one of the few good things of me being COVID bound, is that I can assist under some of my many hats to the various WCPFC meetings I usually can’t… like the Scientific Committee. I’ve written many times about it, and I like to read the papers there presented (open access)… and the ones I always go for are the eFADs ones since is a topic I totally fascinated by, since it changed the fishery in my lifetime. What I mean with this? Simply that the way we were finding fish (and therefore setting up our trip routine and logistics) when I came to the region 30 years ago, and today are totally different worlds, different skills set, different understanding of the fishery. Full stop

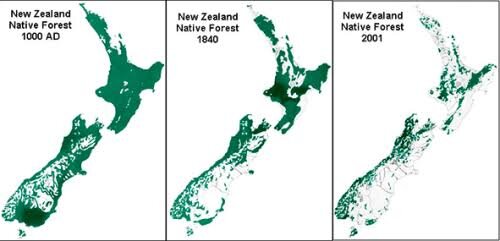

The spatial distribution of dFAD purse seine sets, from all vessels in the WCPO, used for the CPUE analysis, from 2016–2018.

My interest in many of the science papers presented at the SC, have a deeper issue in me… back in the days I put a hell of a lot of my time and frustrations (being dyslexic) into becoming a scientist (MSc Fisheries Science – identification of 3rd reproductive stock of hake) while working as a fisherman... to then be so frustrated with the wimps of Argentina's fisheries institute that I went back to be a fisherman and came to the Pacific, and even if did then 2nd MSc once in NZ (designing a selective bait for longline), I also tendered with industry (and won) research services to NZ Fisheries, I keep reading tons of fisheries papers, I apply a scientific approach to my work in MCS, I review papers on my blog, and so on ... I actually have not worked as a fully focused "scientist" since I left Argentina.

Not that I truly frustrated about it, I have been incredibly fortunate with my work and life…I’m after all a self employed scientist in fisheries, but I would like to experience being part of a group of top scientists, in the search of good and useful questions and answers…

And this is one of those reports that I love reading (and would like even more to have been part of it!)

While eFADs are a divisive issue and many see it as a threat, they are a reality and I always like to look at opportunities from things I cannot change and have many times in the past I thought that if we could harness the data stream of the estimate 40 to 60000 eFADs in our region, we could potentially have some sort of “live” stock assessment capability, and wrote about it in the past.

So my collages from SPC, spearheaded by Lauriane Escalle, who has been working on this for a while presented final results from the WCPFC SC Project 88 ‘Acoustic FAD analyses’ at the latest SC, that explored that idea!

So read the original (recommended), I just will quote the executive summary and the recommendation to the WCPFC

The project sought to identify whether the following objectives might ultimately be addressed using acoustic data from satellite buoys deployed on dFADs:

Whether acoustic buoys on drifting dFADs can provide a novel and efficient source of fishery-independent data for stock assessments (e.g., indices of abundance or additional information for purse seine CPUE standardisation);

Whether limiting sets to only those dFADs that have a large estimated biomass beneath them could reduce the proportion of small bigeye and yellowfin caught.

To evaluate the utility of the acoustic biomass estimates, initial analyses examined the patterns of biomass accumulation following deployment, and related biomass estimates just prior to setting to the resulting catch levels achieved. Following deployment, a clear increase was detected in the estimated biomass up to around 30–40 days post deployment, with a maximum around 60 days. Pattern of biomass accumulation before a fishing set showed an increase through time from 10 to 1 day before a set, with most buoys in the 3 days prior to a set having an estimated biomass between 25 and 60 t (up to 140 t). Examining the level of catch relative to the estimated biomass around the time of setting, larger catches generally corresponded to larger estimated biomasses over a period of 5-days before a fishing set. For very large catch events, the echosounder often underestimated the biomass or alternatively, the whole tuna school was not detected under the cone of the echosounder.

Towards an independent biomass index for stock assessment

For this project objective, the focus was on skipjack tuna given the regional concerns over the reduction in the spatial extent and volume of the current pole and line abundance index for this stock. Two alternative methods were developed to classify echosounder transmissions as a relative index of tuna abundance or as presence/absence of skipjack tuna. The first method is a clustering analysis that classified echosounder transmissions in four different clusters based on biomass at depth, total biomass and biomass accumulation rate. One cluster (0) corresponded to no biomass detected. Two clusters (2 and 3), detecting biomass with differing depth profiles, corresponded to almost all transmissions a few days before a fishing set and therefore likely indicated the presence of tuna.

Finally, the last one (cluster 1), might be a mix of bycatch and tuna. Spatial distribution of each cluster was investigated and clusters 2 and 3 displayed a higher proportion in the main purse seine fishing area, while cluster 0, corresponding to transmissions with no biomass associated to the dFAD, had a low proportion. Higher proportions of cluster 0 were however found outside the main purse seine fishing areas, as expected. General additive models (GAMs) were used to investigate factors influencing total tuna catch. The limited number of skunk sets precluded the investigation of tuna presence/absence. Explanatory variables in the best model of tuna catch explained 25.9% of deviance. An increase in tuna catch was detected with increasing echosounder biomass, up to approximately 150 t, but for larger sets the biomass was underestimated by the echosounder. Other significant variables linked to higher tuna catch were time drifting, higher absolute values of biomass accumulation rates, full moon and higher biomass detected by the echosounder, latitude and longitude (higher tuna catch north of the equator and to the east of the WCPO).

The second method is a Random Forest analysis that classified echosounder transmissions into presence/absence of skipjack tuna, based on a learning dataset of matched observer set/acoustic transmissions and Vessel Monitoring Systems/acoustic transmissions; and buoys with no associated biomass. Skipjack presence generally showed longer drift times (median of 79) compared to skipjack absence (median of 21). Skipjack presence was also associated with higher absolute biomass accumulation rate values. Finally, it was also found that skipjack presence was found in areas with higher vessel density compared to absences. Interestingly, the match in results between the random forest classification and the clustering analysis was very good, with more than 97% of transmissions in clusters 1, 2 and 3 classified as skipjack presence; and 92.7% of transmission from cluster 0 classified as absence.

The classification of presence/absence of skipjack tuna was then used to explore an integrated standardization approach that combines CPUE time series from the purse seine fishery with presence/absence data from acoustic dFAD buoys drifting throughout the WCPO. Two models were compared, both included the WCPO-wide purse seine catch and effort data, while only one included the presence/absence data set. Both models predicted similar patterns, with notable differences in the magnitude of relative abundance; as well as lower predicted encounter probability for the combined data set, and higher predicted abundance during the dFAD closure period. The distribution of skipjack density was also notably different between the two models, mostly due to the information about skipjack encounters from the dFAD network. The positive catch rates showed similar patterns, but with a difference in magnitude. This analysis is a preliminary exploration of the methodology, with a relatively short time-series. These results are not intended to be indicative at this stage, but rather an opportunity to evaluate alternative approaches to obtain more reliable information on trends in skipjack abundance.

While further analyses are required on a larger data set, this preliminary study suggests that acoustic biomass estimates from regional drifting FADs could assist in the development of an independent biomass estimate for skipjack tuna in the WCPO.

Exploration of bigeye and yellowfin tuna proportion in fishing sets related to estimated biomass

Bigeye and yellowfin tuna proportions derived from the catch composition were examined in relation to the levels of total biomass estimated by the echosounder buoys in the days preceding a set. The proportion of yellowfin tuna in the catch appeared relatively constant with increasing levels of estimated biomass, while the proportion of bigeye tuna appeared to increase with higher levels of biomass estimated by the echosounder buoy. GAMs were then used to investigate factors influencing bigeye and yellowfin catch proportions. Explanatory variables in the GAMs explained 23.8 and 27.0% of deviance of the bigeye and yellowfin tuna proportions. Biomass estimated by the echosounder was not significant for bigeye tuna models, but lower yellowfin tuna proportions were found for lower biomass estimated. Other variables influencing bigeye tuna proportions were drift time, low biomass accumulation rates just before the set (2-days), time relative to sunrise, longitude and the interaction between longitude and latitude. Other variables influencing yellowfin tuna proportions were moon phase and longitude. The limited number of sets considered here should be noted, as well as the fact that the echosounder is calibrated to detect skipjack tuna. The presence of a swim bladder for yellowfin and bigeye tuna, contrary to skipjack tuna, might therefore influence the acoustic signal. Accessing data from multi-frequency echosounder buoys that are now more frequently being deployed in the WCPO may allow these analyses to be refined.

While the current analysis suggests little relationship between biomass estimates and the catch proportion of bigeye tuna, statistical models showed a slight decrease in yellowfin proportion for larger estimated biomass. Other factors, including drift time and trends prior to setting (rather than at setting) showing more potential.

It should be noted that the acoustic data available for this analysis represent a small subset, available through partnership with three fishing companies, of the full dFAD network in the WCPO. The assistance of those companies is gratefully acknowledged. Therefore, results presented in this report should be viewed as preliminary and highlighting potential methods to be further explored with a more complete data set. Our intent is that WCPFC members and fishing companies see the utility of the analyses presented, in particular towards improving the monitoring of tropical tuna stocks and encourage or commit to making their acoustic dFAD data available for these endeavors.

We invite WCPFC-SC17 to:

Note the results from Project 88 on acoustic data from echosounder buoys deployed on dFADs.

Note that while the acoustically estimated biomass related to the proportion of bigeye in the catch, this proved non-significant within models, but statistical models showed a slight decrease in yellowfin proportion for larger estimated biomass and other identified variables may show some promise to pre-identify sets likely to lead to greater proportions of bigeye and yellowfin in the catch.

Note the potential, over the longer-term, to use echosounder data as a source of fishery-independent data for stock assessments, either as an independent relative index of abundance or to provide additional information for purse seine CPUE standardization.

Recommend the need for better identification of particular dFAD buoys (e.g., via the buoy identification numbers) by commercial vessel operators or via observer reports.

Endorse the continued cooperative relationship with the fishing community to obtain commercially sensitive data for analysis for the purpose of scientific and other research, particularly with regard to dFADs, and the fishing strategies involved in their use

Highlight the need for additional data covering the whole WCPFC convention area, including that from now available multi-frequency echosounder buoys, and encourage other industry partners to become involved in the project.