I know David from his work on fisheries subsidies, an area of my strong interest… Fuel is the single most important operational cost across all fleets, subject to the largest fluctuations across all cost categories and, hence, a major determinant in the change in fishing costs over time. Fuel makes up an average of 30% of operational costs, with variability depending on the age and condition of the vessel in the longline fleet here in the Pacific, and such is the focus of most subsidies… while I see an inevitable decline in the Longline fishery as the money isn’t there, yet its geopolitical value is immense for the DWFN (if you have a presence, you have rights) and LL are relatively cheap to subsidise (since they pay crew shit and they bunker at sea paying under-market value fuels not subjected to taxes

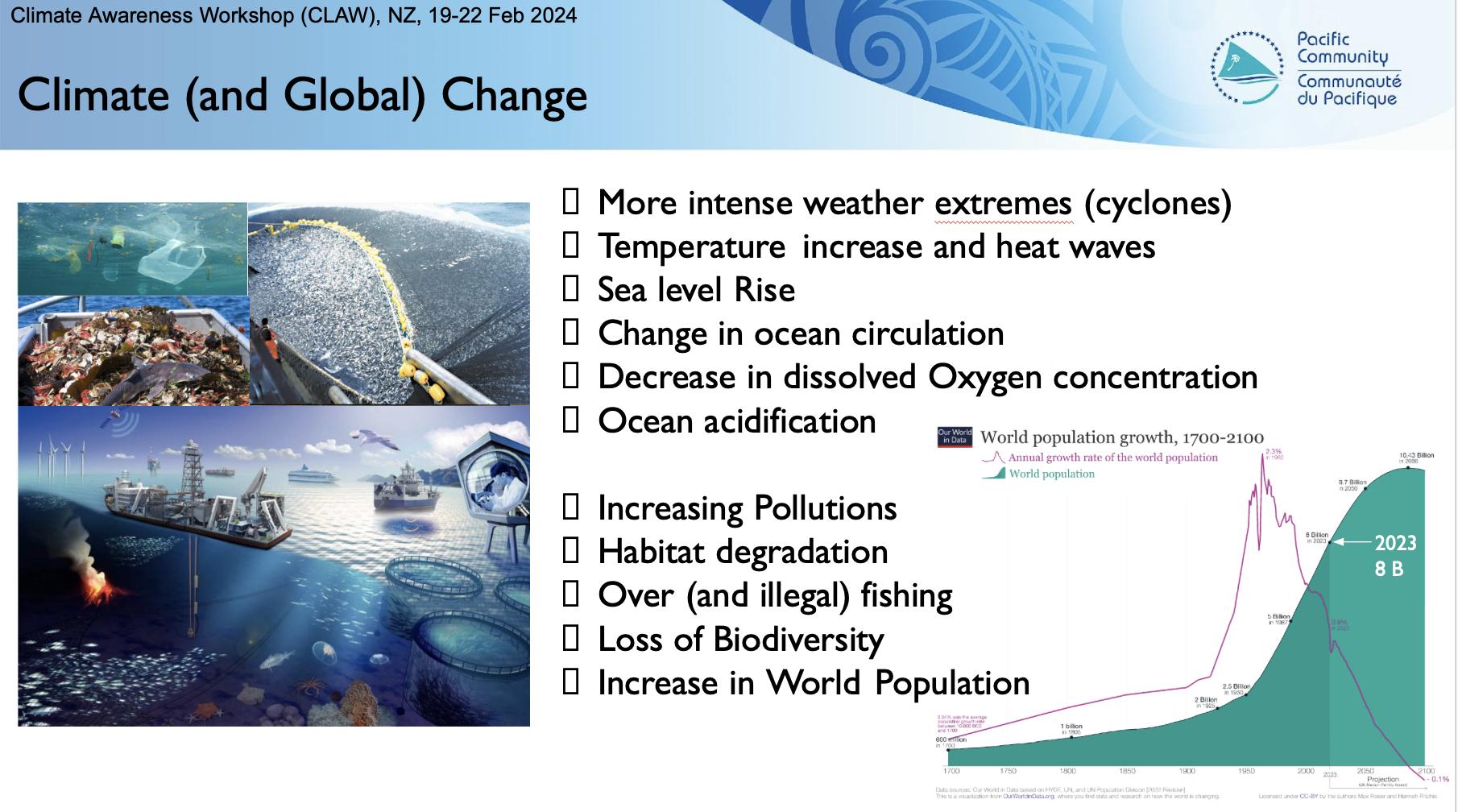

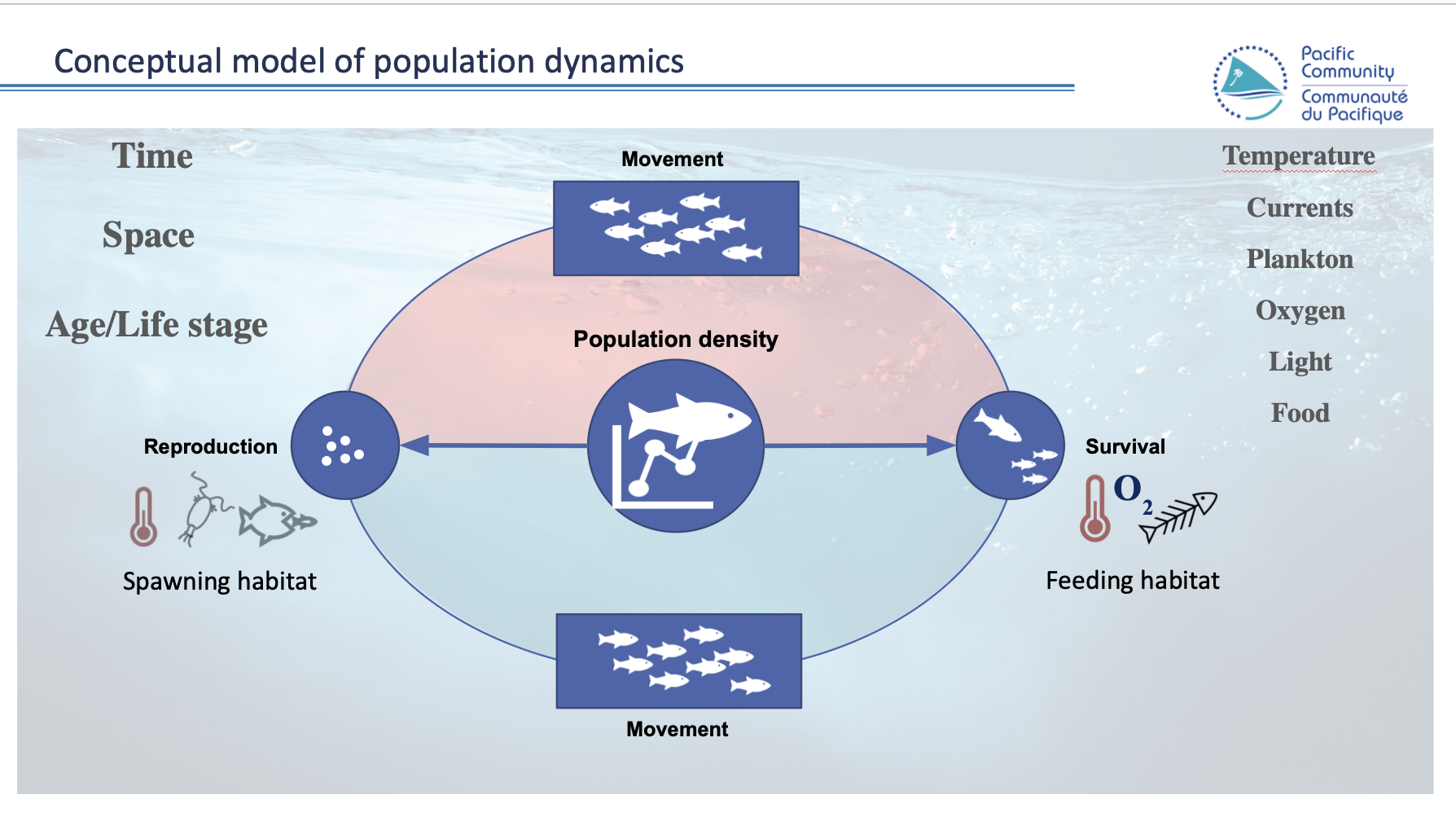

The reality is that Climate change is really impacting Pacific fisheries… but how much do fishing vessels impact the climate? What is their emission profile?

I questioned this in the past when I heard recreational fishers bragging about their allegedly minor environmental impact… they seem to cherry-pick out emissions.

On a good weekend, you may have 1000 recreational fishing boats out in the Hauraki Gulf, and let’s have a conservative average of 100HP per boat, which is 100000 HP… a longliner may bring 3 to 4000kg of fish on 400HP, and only 4 of those 1000 may bring 40Kg; hence the emissions per kg of fish are off the charts.

The basis of the publications is very sound, and I strongly suggest you read it, if you are interested in the overall impact of fishing in comparison to other forms of primary production.

I quote here the Executive Summary.

As more countries commit to net-zero emissions and include ocean-based climate action in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs), the energy transition of the fishing industry and its fleets is becoming a pressing issue. The fisheries sector is a contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions because of its heavy reliance on fossil fuels.

In total, fishing vessels contribute between 0.1 per cent and 0.5 per cent of global carbon emissions, representing about 4 per cent of carbon emissions from global food production. Because of a lack of data, emissions from fishing fleets are estimated with different methods (bottom-up vs top-down). The International Maritime Organization (IMO) finds an increase in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions using a bottom-up analysis, versus a decline using a top-down (or macro) approach. Academic studies estimate that the world’s fishing fleets emitted 179 million tons of CO2 in 2011 and 159 million tons in 2016.

Asia has the largest fishing fleet, producing the most CO2 emissions, followed by Europe and Africa. Based on notifications made under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the European Union, Japan and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland have reduced the emissions of their fishing fleets by between 20 and 45 per cent over the past 20 years due to a reduction in fleet sizes and energy efficiency gains (e.g., in fuel use, efficient engines, lighter fishing gear, and smart navigation and fishing methods).

The IMO recently adopted a revised GHG strategy for global shipping (IMO, 2023a) that seeks to reach net-zero GHG emissions from international shipping close to 2050 and a commitment to ensure an uptake of alternative zero and near-zero GHG fuels by 2030. While not specifically targeting fishing fleets, the revised IMO GHG strategy is likely to accelerate the deployment of low and zero emissions technologies and fuels, and their related infrastructure in the fisheries sector. Any strategy for energy transition in the fisheries sector should be coordinated and build on that of the shipping sector because regulatory and technological developments are in a more advanced stage in that ocean economic sector.

To date the application of energy efficiency regulations to fishing vessels has been effective but rather limited. This is primarily due to their size, propulsion type and operational patterns. Fishing vessels that fall below certain tonnage thresholds or operate exclusively within a flag State’s jurisdiction are exempt from energy efficiency measures, but some larger fishing vessels may need to comply in the near future. The energy transition of fishing vessels, and fisheries in general, lag behind the decarbonization of the shipping industry, lacking global targets and implementation guidelines and related research and development (R&D).

The fisheries sector plays a crucial role in food security and livelihoods, with more than 40 million fishers worldwide, many of them located in developing countries. However, due to volatile fossil fuel prices and increasing climate impacts, there is a need for urgent support to ensure a swift energy transition for the fisheries sector, with special attention paid to small-scale and artisanal fishers and female fisheries workers.

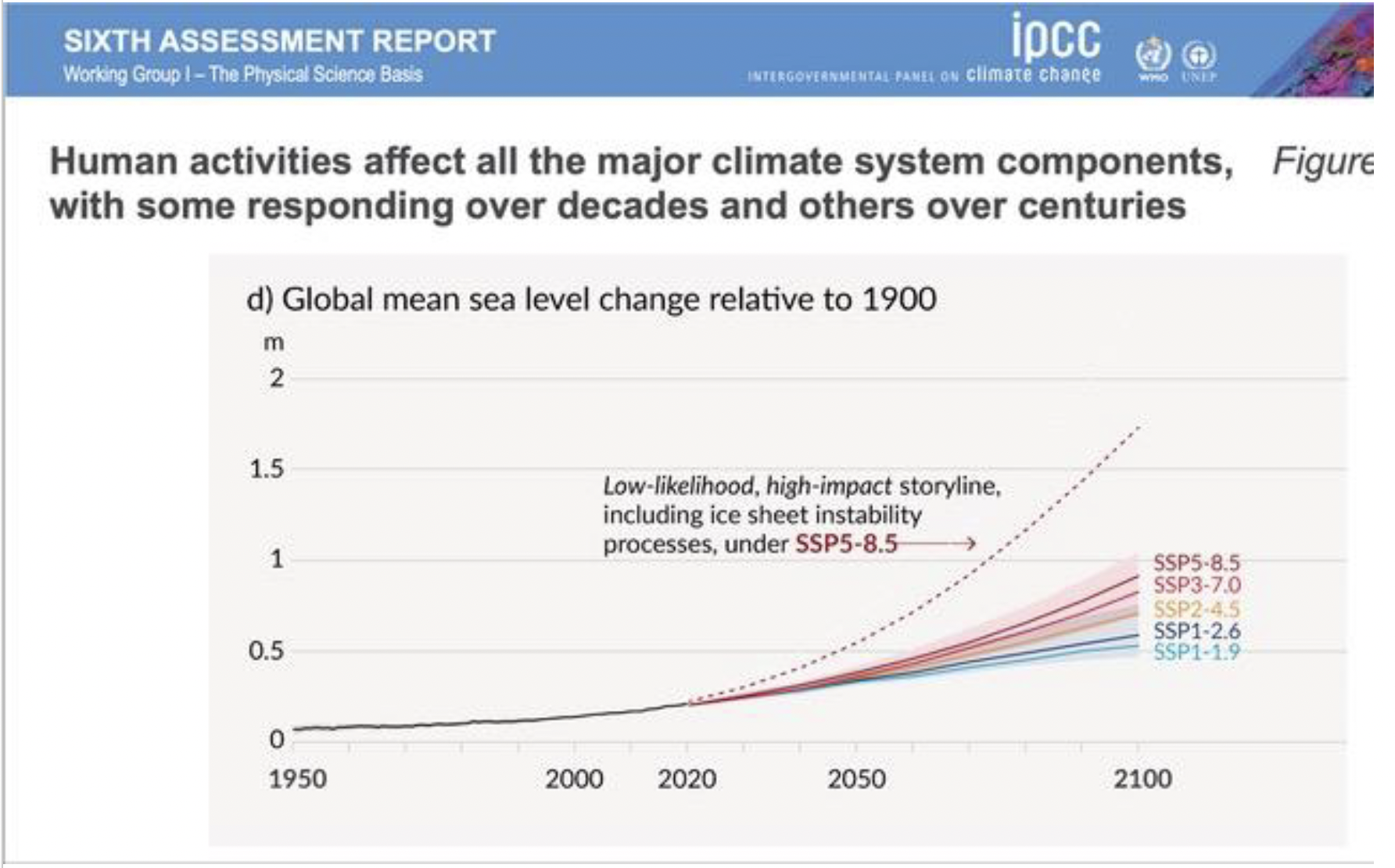

With agriculture and tourism, the fisheries sector is one of the three economic sectors most vulnerable to climate change. The main causes for concern are rising sea levels, warmer water temperatures and ocean acidification – and their impacts on fishing activities – particularly in least developed countries (LDCs) and small island developing States (SIDS). While non-motorized fishing vessels are emissions-free, artisanal fishers face fish stocks decline because of climate change. They need public support to adapt to climate change and improve their livelihood. On the other hand, motorized fishing vessels need support in shifting to renewable and clean energy resources. This applies especially to small-scale fishers.

Policies to incentivize or mandate the energy transition of the fishing fleet cannot be designed without considering trade-offs and co-benefits. For example, increasing the fuel efficiency of engines may not improve fuel efficiency in terms of litres of fuel per ton of catch if overfishing continues. Canada and Norway, for instance, have the most fuel-efficient fishing vessels, while the European Union and the United Kingdom have lower fuel-efficiency, largely due to more intense competition for catches.1 Similarly, industrial fishing fleets, which are more fuel-efficient, can undermine small-scale fishers if they are allowed to compete in the same marine areas or fish for overfished shared resources.

The review of NDCs conducted in this study shows surprising results. It reveals that three major aquatic food exporters show no commitments on the ocean or fisheries-related matters. In contrast, countries such as Canada, Chile and the Russian Federation have committed to protecting ocean space and include climate mitigation and adaptation measures within marine protected areas. And, despite being a part of the most polluting region in the world, China and Viet Nam stand out for committing to implement measures for energy saving, energy efficiency and emission reduction in fisheries as a means of mitigating GHG emissions. The review of regulations and agreements found little evidence of such measures being used in the fisheries sector.

At the European Union level, regulatory initiatives have been introduced to address GHG emissions from maritime transport. The inclusion of shipping activities in the monitoring, reporting and verification of CO2 emissions from maritime transport (MRV) Regulation and the Emission Trading System (ETS) of the European Union, may have some implications for the fishing industry, albeit indirectly. While fishing vessels have been excluded from certain reporting obligations and market-based mechanisms, the European Union has recognized the importance of fair contributions across all sectors to achieve climate neutrality and Member States are required to take necessary measures, including at the national level, under the European Union Climate Law, which has been directly applicable and effective since July 2021. This suggests there is potential for the future inclusion of fishing vessels in emission reduction measures, as well as potential taxation of energy products used for propulsion.

When zooming in on the fisheries sector, certain forms of (fuel) subsidies clearly contribute to overfishing because they expand the capacity of fishing fleets. According to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), China is the biggest provider of fishing subsidies in value, followed by the United States of America, Japan, Canada and the European Union. About 80 per cent of all fisheries subsidies, including fuel subsidies, are directed to industrial fleets. Most LDCs and SIDS do not provide, nor do they have the financial capacity to offer considerable subsidies, particularly for industrial fishing. The World Trade Organization (WTO) Fisheries Subsidies Agreement reached in 2022 prohibits certain fisheries subsidies that contribute to illegal fishing and fishing on overfished stocks and is a significant step towards phasing out fisheries subsidies. However, negotiations are still ongoing for additional provisions under a comprehensive agreement to address issues related to overcapacity and overfishing, including fossil fuel subsidies. Phasing out fuel subsidies and shifting resources to support the energy transition of small-scale fisheries are essential to address overfishing and GHG emissions.

This study finds several alternative energy sources for fishing vessels at different levels of commercial development, such as green methanol, liquified natural gas (LNG), biogas, green hydrogen and wind propulsion. Each option has its challenges and opportunities. Green biofuels, made from non-food feedstocks or fish waste, stand out as the most readily available and mature fuel option for fishing vessels. Green methanol and LNG give rise to challenges in terms of retrofitting, safety and limited potential to fully decarbonize. Green hydrogen and green ammonia show promise but require further R&D to address safety risks, scalability, cost-effectiveness, the storage capacity of vessels and ports, and delivery infrastructure. Onboard carbon capture only shows promise in the middle to long term. Ultimately, the choice of alternative fuels depends on the specific technical requirements and capabilities of fishing fleets, the crew and the type of fishing activity, as well as coordination and cooperation across the world to ensure access to alternative fuels wherever a fleet may operate.

Another approach involves utilizing electric engines and hybrid engines, which can be powered by renewable energy sources such as solar panels. These engines offer a clean and quiet energy option. Electric engines are particularly suitable for smaller fishing vessels and short trips close to shore. Hybrid engines, which combine batteries, fuel cells and traditional engines, offer greater autonomy and flexibility for longer trips. This study also explores emerging wind propulsion as an attractive and carbon-neutral option for vessel propulsion for fishing and tourism activities through innovative technologies.

Energy efficiency measures, such as digital tools and optimization methods, can be integrated into fishing vessels to enhance performance and reduce energy consumption. While on-board carbon capture could play a role in maritime decarbonization in the long term, the technology is not yet mature and faces high costs. Overall, technological alternatives such as alternative fuels, electric engines, hybrid engines, wind propulsion and energy efficiency measures, offer potential solutions to reduce GHG emissions in the fisheries sector and contribute to the just energy transition. However, each alternative presents challenges and limitations, requiring continuous R&D to fully realize their potential.

Four case studies from diverse regions at different levels of development and with uniquely sized fleets offer valuable insights and can be found in Annex 3. For instance, the Ecuadorian experience shows efforts to measure the carbon footprint and introduce carbon-neutral production in the tuna value chain. The Asia-Pacific region focuses on clean energy and emissions targets but faces challenges related to capacity building, financing and regional strategies. In Europe, alternative renewable energy sources are not yet available for fishing fleets at a commercial scale and the region is focused on reducing energy consumption, improving efficiency and introducing circular economy schemes. The fourth case study provides an example from the private sector to achieve carbon neutrality by 2040 through emissions reduction and compensation.

Accelerating the energy transition of fishing vessels will require collaboration and cooperation among stakeholders, governments, international organizations, research bodies and the private sector. Enabling coherent strategies, sharing technological advances and introducing financial incentives are essential to achieve a just energy transition for fishing fleets, particularly in developing countries and for small- scale fisheries. Additionally, further research on sustainable fisheries management and ecosystem-based approaches, and their links to energy transition, is needed.

The transition should focus on a balanced approach that encourages trade and investment in a sustainable energy mix and promotes the incremental adoption of renewable technologies that mitigate impacts on small-scale fisheries and marginalized fisherfolk. The following are some of the economic and technological, trade, environmental and social considerations that are proposed and developed in detail in the report.

1. Economic and technological considerations

Develop and implement comprehensive national mitigation and adaptation plans for the fisheries sector, prioritizing a just energy transition that involves all stakeholders along the entire fishing value chain and national energy matrix.

Building on the experience of the IMO and FAO, establish a globally harmonized system for data collection, monitoring and reporting of fishing fleet emissions adapted to small-scale and artisanal fisheries.

Explore and adopt sustainable fuel options from circular economy practices, such as transforming fish waste and seaweed into biofuel or biogas for fishing vessels. Such transition implies retrofitting or adopting new engines and vessel design, efficient fishing practices and adequate port infrastructure.

2. Trade, value chain decarbonization and trade-related infrastructure considerations

Explore the need to develop specific Harmonized System codes for the latest renewable energy goods and related technologies.

Incrementally phase out and ultimately prohibit fossil fuel-based subsidies to the fisheries sector.

Incorporate carbon footprint criteria for fish and seafood products into voluntary standards or consumer seafood sustainability guides.

Develop and implement effective measures on climate change adaptation, resilience building and disaster risk reduction (DRR) for seaport infrastructure on which fisheries activities depend; and improve access to affordable financing for developing countries.

3. Environmental considerations

Develop and agree on a specific and measurable global emission reduction goal for fishing fleets and on effective regulatory measures that are applicable to fishing vessels.

Include specific objectives for emission reduction and adaptation for the fisheries sector and fishing fleets in the revision and updates of NDCs and scale-up mitigation commitments (by major aquatic food traders and fishing nations).

Bolster efforts to reduce fishing fleet emissions with effective stock and ecosystem management and restoration.

4. Social considerations

Ensure that the shift towards renewable and sustainable energy sources promotes a just energy transition that also prioritizes the well-being, livelihoods and rights of fishers and their families.

Revitalize the ratification and implementation process of the International Labour Organization’s (ILO’s) Work in Fishing Convention (C188) that ensures minimum working conditions, occupational safety and health and social security in the fisheries sector.

Enhance fishing safety and prevent marine pollution by encouraging ratification of the IMO Cape Town Agreement and enforce the agreement to establish comprehensive safety standards for fishing vessels once it is in force.