Continuing with my Climate Change in Fisheries Series (CCFS), here is my 2nd on the Introduction to IPCC Scenarios by Dr Elizabeth Holland

I met Elizabeth at my friend Bob Gillet's house in Lami (near Suva) quite a few years ago. While she was the head of the Climate Change programme at USP, we went on the usual Sunday morning cycling mission to the Pacific Harbour. She came over to join us, and we had a great chat. We have been acquaintances since then.

She is climate science royalty after over 30 years of climate change research experience in the Pacific. She is now a Distinguished Research Fellow at the Institute for Strategy, Resilience, & Security at University College London (UCL); she served as an author in all six cycles of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, including the recent Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Holland won the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize as part of the IPCC, and has been honoured as a Leopold Fellow, Bjerknes Fellow at the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research at UiB, and Fellow of the American Associate of the Advancement of Sciences in Atmospheric and Hydrological Sciences.

She is like an aunty figure to many Pacific climate scientists, students, and communities working to build climate- and disaster-resilient futures. You hardly find anyone who is as caring yet qualified as she is, but most importantly, who is profoundly committed to CC science and activism. So much so that she had death threats and had a security attachment while working on the IPPC reports.

As I expected, her presentation was flawless from the technical side, but it was also really moving and a call to action. It was the 1st of these sobering moments I had that week.

Her presentation clarified the role of the IPCC, including an overview of (Representative Concentration Pathways(RCPs), and explored how climate models predict future changes in temperature, currents, and ecosystems.

Her overview of the Sixth IPCC Assessment Cycle (AR6) included a series of Special Reports including the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C and the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) requested by Pacific leaders. The first IPCC Assessment report was released in 1992 and the most recent report was released in 2023. The IPCC is the authoritative voice summarising the state of the climate and projected impacts.

The ocean is the largest thermal sink for climate warming. The ocean has warmed to below 2 km deep, ocean pH has declined with resulting ocean acidification. Marine heatwaves are increasing in frequency and extent. Deoxygenation of the ocean, decreased pH, increased ocean acidification are all changing that state of the ocean. The top three Greenhouse Gases (GHG) are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O).

To understand the increase in GHG concentrations in the atmosphere, it is important to understand the global and local carbon cycles. The state of the carbon cycle was presented, covering emissions and the importance of sources and sinks in determining atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, the most important greenhouse gases involved in climate change.

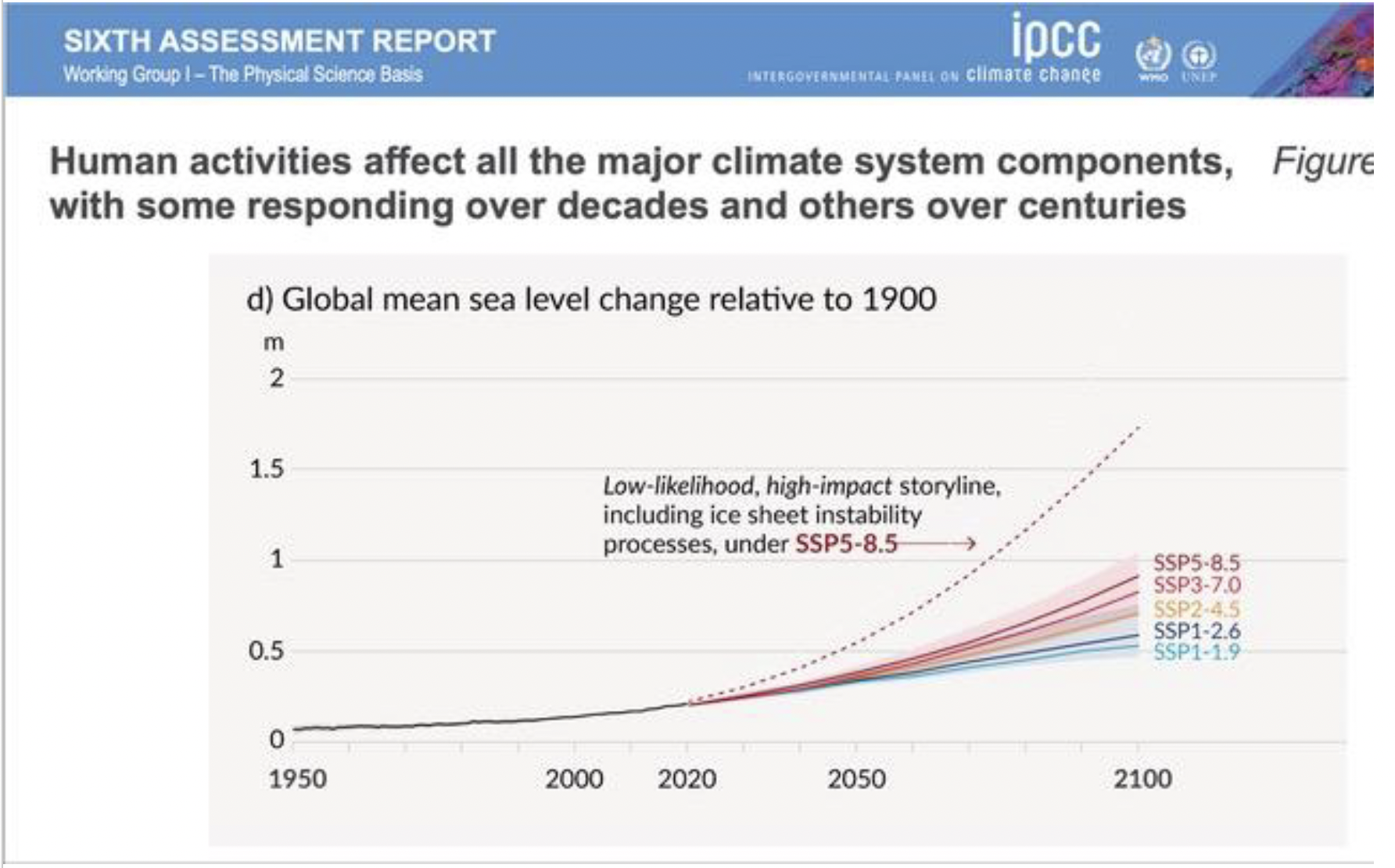

The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) scenarios used in the AR6 project show a range of temperature increases from 1.5°C to more than 4°C of surface warming in our changing climate.

At the higher SSPs with increased GHG emissions and associated warming, the ocean is unable to continue to remove the carbon dioxide from the atmosphere thus increasing the proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at the higher SSPs.

The combined effects will further accelerate warming and thus further amplify the impacts including acceleration of sea level rise. Only the SSP1 scenarios, SSP1-1.5 and SSP1-2.6. ensure that Arctic ice sheets are protected throughout the year.

The SROCC, the AR6 reports, and the special reports highlight the need for urgent action to decrease GHG emissions. Sea level rise projections for 2300 increased to 5.4 m, with further increases possible for the high impact/low probability projections of sea level rise that include a more detailed presentation of ice loss.

At 1.5°C of warming, there is a high risk of losing 70 to 90% of global coral reefs and associated services for humankind, with even more loss at 2°C. The ongoing strong El Niño resulted in dramatic ocean warming, and the global mean temperature increase exceeded 1.5°C in June 2023.

Discussion

It was suggested that for a fisheries audience, IPCC could be considered similar to a fisheries management strategy evaluation, and we can use it to develop options for to explore how the world may work under alternative climate change forecasts.

There was a lack of information from the Pacific in early IPCC reports. As such it was felt that there is a need to focus more on the Pacific, and that Pacific-based climate scientists and managers should work harder to bring this information to the forefront of international discussions.

It was noted that capacity within the region is growing, and as an example, over the last few years, within the region, more than 200 postgraduate students have completed theses on climate-related work. In addition, some New Zealand universities, such as Canterbury, are doing more work using Pacific data, which gets 4this information into peer-reviewed journals. However, there is still a need for more information on local Pacific knowledge and local descended knowledge that needs to be elevated to the international community.

It was noted that climate scientists are concerned about the impact of climate change on the future of the planet's habitability. However, there is no official climate change doomsday clock to summarise the combined impacts of all climate-related issues. What we do know is that currently, we are running out of carbon budget, but there is no clear plan as to what to do when it is reached or exceeded. There is also no common agreement about which method to use to predict and capture carbon requirements in the future.

The lack of a single body regulating emissions was noted. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has no responsibility over bunker fuel or aviation fuel. Bunker fuel is regulated by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), and aviation fuel is regulated by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). Neither of these entities is responsible for any climate-regulated activities. This is problematic, and agreements on who takes the responsibility still need to be resolved and where the boundaries for that responsibility lie. For example, for an airline or shipping company, who pays for the carbon? Is it the purchaser, airline/shipping company, country of destination, or country of departure? Under the climate change convention, developed and developing countries also have different responsibilities. This concept is not in the IMO or ICAO.

As a country with a large fleet of ships, the Marshall Islands has started to do this voluntarily, but shipping companies are trying to avoid levies and resist changes. To clarify the scale of the situation, SPC is developing a system to house extended knowledge on bunker fuel and related issues.

Models for predicting the impacts of climate change are good and getting better as we get more information to feed into them. Some areas, such as the carbon budget and the impact of carbon, are well-refined, and the science community has a high degree of certainty in them. There are areas where improvement is needed, but the diverse community hinders some of these. Moreover, some of the models result from a negotiated outcome and, as such, are likely to be conservative. To make things more explicit and meaningful for non-experts, the IPCC should put statements into threshold groupings for clarity.

However her last slide is the one the hit me the most