Yes, it's another of my FAD-related blogs, but the magnitude of the shift caused by drifting eFADs in the purse seine fishery cannot be overstated. If we discover a disruptive event akin to a miracle sun flare, and all FAD data would NOT be redirected to vessels and fleet offices, this could collapse the canned tuna industry as we currently know it, for good and for bad.

If there is no FAD fishing, I think only half the fleet will be economically feasible. This would be good for stocks but bad for those who make a living from it… including coastal states at this stage. Also, I don’t know if there is enough experience in free school fishing still in the fleet… not just at the bridge level… but well on the deck. Setting the purse seine on a free school is WAY fiddlier than setting on a FAD.

In any case, some of my questions about the impact of a fully respected FAD closure on the fishery and its economics have actually been answered… but not in the WCPO but in the Indian Ocean.

Last December, the WCPFC agreed to a 45-day closure, down from a long-standing 90-day one… and I wondered if any economic analysis was done on that.

In any case, this is a Nature paper, where my mate and fellow dub-head Alex Tidd is involved: Macroeconomic impact of an international fishery regulation on a small island country

As usual, read the original; here are the bits I like the most.

Introduction

Drifting fish aggregating devices (dFADs) are under scrutiny in the global tuna fishery because of their massive use in the oceans, their significant contribution to the growing fishing capacity of industrial purse seiners, and their negative externalities (e.g., bycatch of endangered and protected species such as pelagic sharks or loss at sea after sinking or stranding, leading to increased marine pollution and habitat degradation)

Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) have established management plans to curb the intensive use of dFADs by implementing spatial or seasonal closures, limited deployment, and purchase of buoys per vessel, restrictions on dFAD sets, etc. However, the best intentions of dFAD management measures can also have unintended environmental or economic impacts.

In February 2023, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), the RFMO responsible for tuna management in the Indian Ocean, voted in favor of a resolution to create a 72-day seasonal dFAD closure from July 2024. This resolution came from a group of contracting cooperating parties (CPCs) who have experienced the adverse effects of dFADs. However, many other CPCs have objected to this resolution (in September 2023, at least eleven states had objected to this management measure: Comoros, Oman, Somalia (withdrew on March 25, 2023), Philippines, Seychelles, Kenya, European Union, France, Tanzania, Yemen (withdrew on August 8, 2023), Mauritius, Thailand, and Republic of Korea.

Objecting members representing more than one-third of the 30 IOTC members, even the non-objecting members “shall not be bound by that measure” any longer (IOTC Circular 2023-51, August 8, 2023)), including developing and coastal states that are economically dependent on tuna landings from industrial purse-seine fisheries. Although the need to restrict the development of dFADs is recognized by most experts around the world, the consequences of management plans in all their dimensions are insufficiently considered.

The present research is focused on the economic consequences of an international regulation (dFAD closure) for a small country that would lead to a sharp decline in its exports of canned tuna.

Interactions between shared stock fisheries

The literature on fisheries management policy focuses on management’s effectiveness in preventing stock depletion and overfishing9,10,11. Maintaining fish stocks within safe biological limits and achieving a maximum sustainable yield (MSY) remain the cornerstones of natural resource management. This is because the conservation of biomass and biodiversity should support all other dimensions of sustainability, including economic or social aspects such as the role of women in fisheries12. However, in most cases, management measures are designed for each individual species and stock without considering the consequences for the entire ecosystem from which the resources are extracted or the social and economic consequences that the decisions may have on coastal communities13,14.

In tropical tuna fisheries where mobile stocks are shared, interactions initially occur at different age classes between surface and deep-sea fishing gears (e.g., purse-seine and longline). For example, purse-seine fleets using dFADs and pole-and-line fleets target juveniles of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), while longline vessels catch more adults of the same species.

Harry Campbell estimated what an optimal allocation of yellowfin catches among the three gears (purse-seine, longline, and pole-and-line) might look like. He relied on an earlier estimate of catch interactions between 1978 and 1989, which indicated that a 1% decline of catch per unit effort (CPUE) in the purse-seine fishery corresponded to a 1.68% increase in CPUE in the longline fishery eighteen months later. However, he preferred to use a more conservative response of a 1% increase in longline catches for every 1% decrease in purse-seine yellowfin catches. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to demonstrate a clear causal relationship between the catch dynamics of yellowfin tuna and bigeye tuna (T. obesus), which have been fished in the Indian Ocean since the 1950s, despite the enormous expansion of purse-seine fisheries since the early 1980s.

More recently, Ovando et al. studied the bigeye tuna fishery in the West Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) and attempted to estimate the social cost of bigeye tuna conservation in terms of forgone catches of skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) with dFADs. The authors estimated that the MSY of bigeye tuna can only be achieved at the cost of withdrawing three-quarters of the effort on dFADs, which would simultaneously reduce the catch of small bigeye tuna and yellowfin tuna, but also of skipjack. In such a case, the net welfare result would lead to a loss of USD 1.2 billion and would primarily affect the Pacific Small Island Developing States (SIDS), while only Japanese sashimi consumers would benefit. They concluded that only a limited dFAD removal (~15%) would bring social benefits that exceed costs.

Economic effects of dFAD management on SIDS

The economic consequences of dFAD management can also be severe for contracting parties. In the WCPO, SIDS would be the first losers from a substantial reduction in dFADs. The Vessel Day Scheme allows small island countries to sell effort rights in their EEZ (access fees) to the vessels of distant water fishing nations (DWFN)10,20. This system would become less profitable, and the value of the VDS license could decline significantly if dFADs were prohibited or severely restricted. Recall that fishing access fees represent more than 50% of government revenue for Tuvalu, 70% for Kiribati, and more than 80% for Tokelau. In the coming decades, climate change will reduce and spatially redistribute tuna biomass, eliminating a significant portion of this revenue for a number of Pacific SIDS (Ibid.) and also for territories located in the Indian Ocean.

Tuna-dependent economies will not be the only ones to suffer from a seasonal closure of dFAD fishing every year. Purse-seine fleets around the world are increasingly dependent on dFADs because they use larger vessels, supply boats to support them, and use sophisticated electronic equipment such as echo-sounders to detect fish biomass under dFADs, etc

It has been estimated that a six-month dFAD closure in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans would reduce the catch by 600 to 1800 tons per boat per year, i.e., 12% to 37% less catch, depending on the season and conditions under which this dFAD restriction measure is implemented. In the WCPO, the economic loss would amount to 15% of the vessel’s revenue, i.e., on average, USD −250,000 per fishing trip. The economic prosperity of small developing states relies often on the fish landed by these industrial fleets.

The economic development of small island territories is based on many port activities and fish-related jobs such as stevedores, fuel suppliers, shipping agencies, fishing equipment manufacturers, warehousing agents, sea transporters, fish processors, seafood traders, etc

Conclusive remarks and limitations of the study

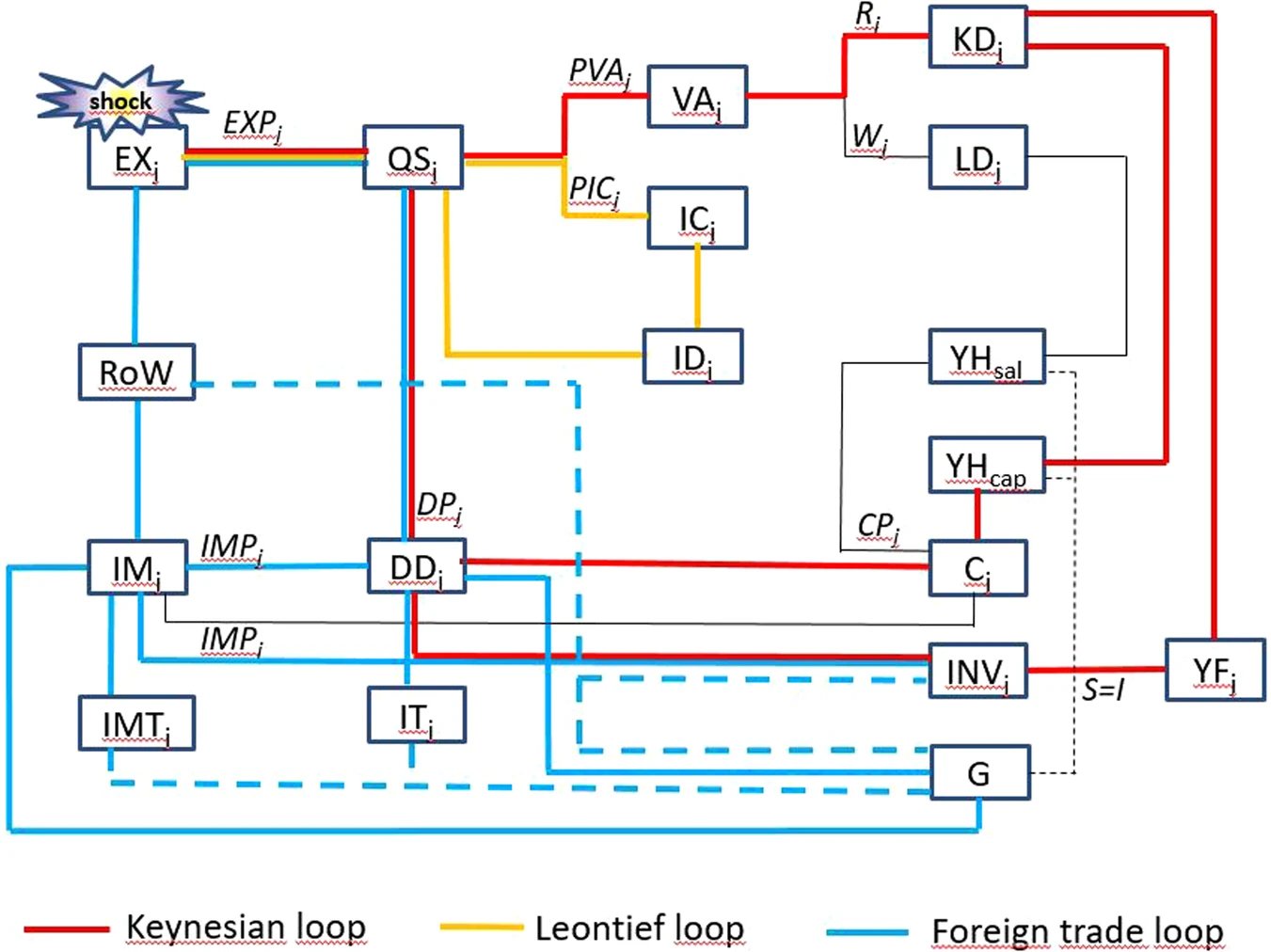

In this article, we have examined the macroeconomic consequences of an international fisheries management measure for a small open economy. The recent IOTC decision on a 72-day closure of the dFAD fishery for the Indian Ocean purse-seine fishery could lead to a shortage of fish supply for tuna-dependent areas and affect other activities and institutions through a chain of cascading effects. Using a dynamic general equilibrium model applied to the case of Seychelles, we examined the spillover effects of a 12% decline in fish exports for this country.

We show that this shock to foreign demand affects all industries and institutions in this small open economy that specializes in tourism and fishing. The shock wave spreads rapidly to the domestic demand for all goods and services through the decline in capital income. The IMF’s projected growth trend of 3–4% is undermined by a deviation of nearly 9% after seven years, resulting in a change in GDP of −5% or −6%, with the impact compounding over time if other factors remain equal, i.e., in the absence of countervailing economic policies or international support.

All the drivers of aggregate demand are affected (household consumption, investment, government spending, etc.), starting with the most important one (exports), so that the entire domestic economy depends on foreign visitors and tourist activities, increasing its vulnerability to a new shock such as a pandemic or an international crisis. The overall effect on the domestic economy is comparable to a strong ENSO event, as shown in the past (1998) for this small island territory.

Several limitations of the study can be put forward. The first one concerns the hypothetical case itself, which is not likely to happen since one-third of the IOTC members have objected, thus canceling the dFAD management measure. The shock is therefore certainly overestimated because a re-allocation of the fishing effort to free school fishing or substitutes of raw material inputs for the tuna cannery may occur if the measure is implemented. A second one lies in the lack of recent data to build an updated version of the social accounting matrix.

However, what matters is the deviation trend after the shock, rather than the accuracy of the outcome itself. In future research, more comprehensive analysis should be undertaken to assess the effects of dFAD management at the overall scale of the Indian Ocean tuna fishery. This analysis should involve all fleets and all CPCs, with the aim of establishing a fair and sustainable agreement.

Notes: j stands for sectors or products, EX = export, IM = import, QS = aggregate supply, DD = aggregate demand, VA = value-added, IC = intermediate consumption, ID = input demand, KD = capital demand, LD = labor demand, YHsal = household’s salary income, YHcap = household’s capital income, YF = firms’ revenue, C = consumption, INV = investment, G = government, RoW = Rest of world, IT = indirect taxes, IMT = import taxes, EXP = export price, IMP = import price, CP = composite price, PVA = price of VA, PIC = price of intermediate consumption, W = wage, R = interest rate, S = savings. Links represent income or expenditure. Dashed flows represent transfers (taxes, savings, social transfers, grants, remittances, etc.).