Everyone is talking about it, so I thought about giving it a go since my website/blogging platform offers it for free.

I asked AI to write about IUU and if fisheries ecolabels are any good?. To be honest, I’m mildly impressed, and it would be stupid for political speech writers and journalists not to take a hint since it is much better than many of the speeches that I heard ministers say or "news" that one reads normally.

Overall nothing new… but congruent nevertheless… yet we shall see where all this takes us. May I ask about it again in a year.

Decide for yourself; this is verbatim what AI “wrote”:

Tell me about IUU fishing.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing poses a significant threat to the sustainability and health of our oceans and fisheries. As global demand for seafood continues to rise, combating this detrimental practice becomes increasingly crucial. Fortunately, governments, international organizations, and local communities have been working tirelessly to address IUU fishing and implement measures to protect our marine resources.

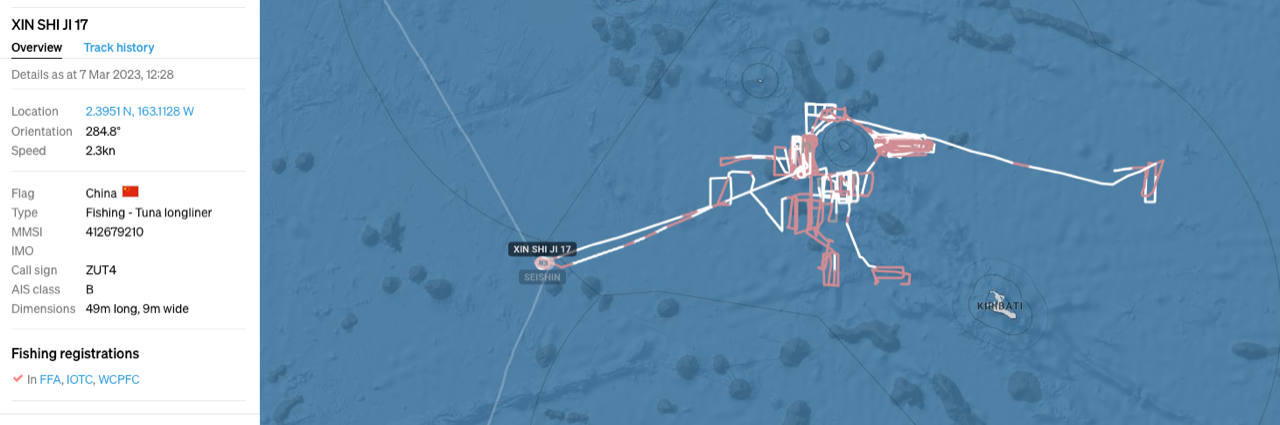

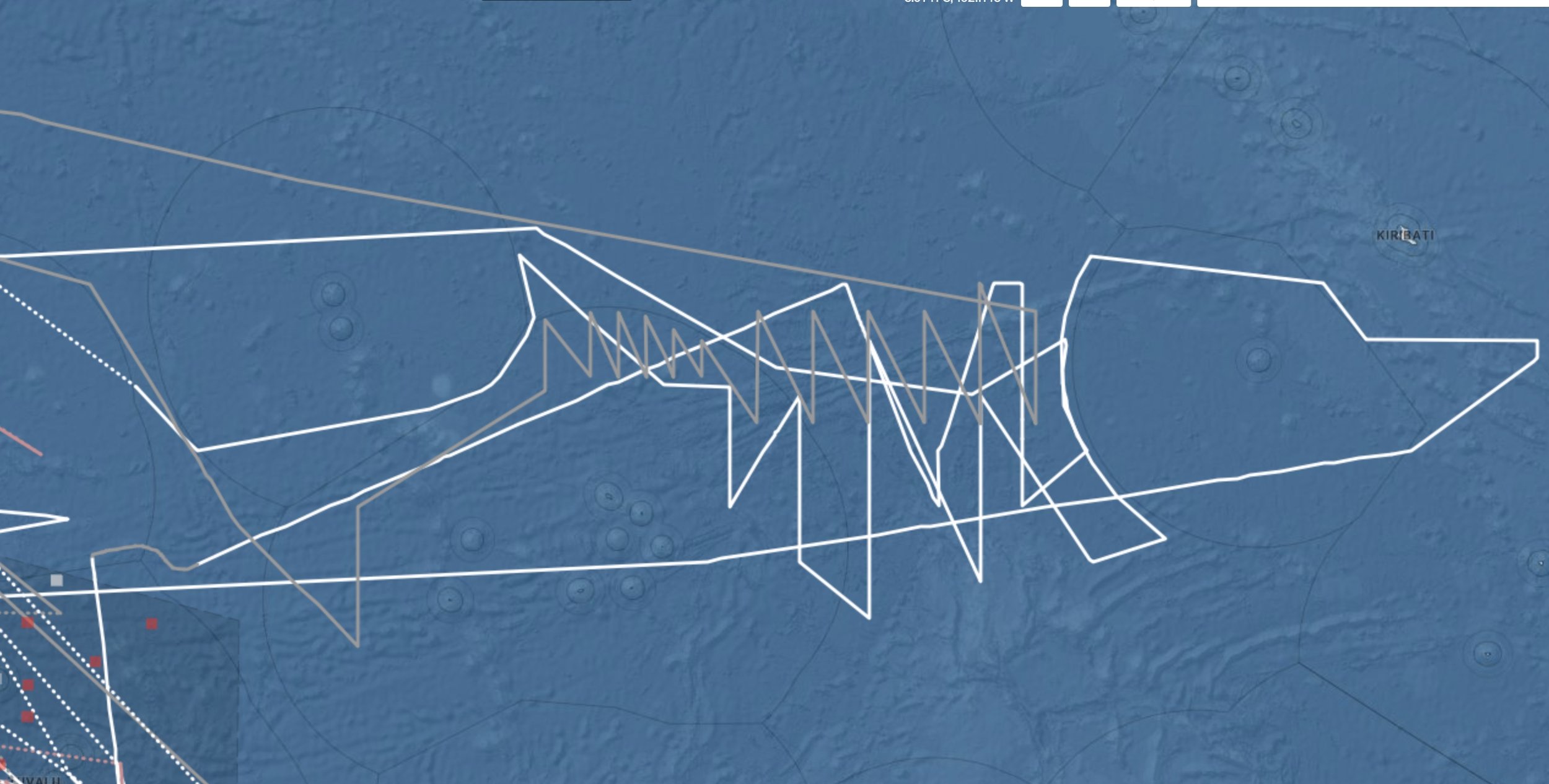

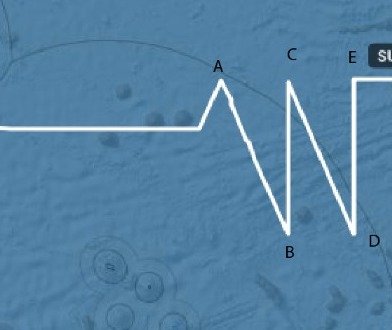

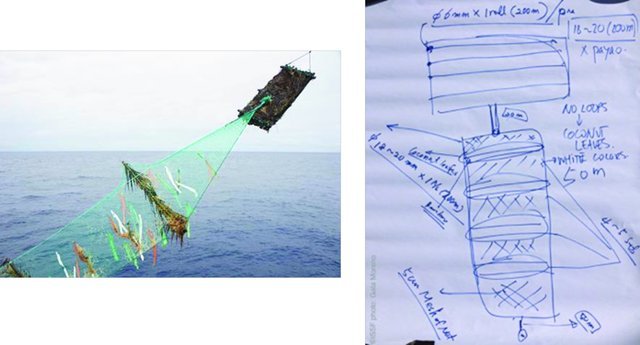

One of the primary strategies used to combat IUU fishing is the establishment and enforcement of stricter regulations and laws. Governments around the world have recognized the urgency to defend their marine ecosystems and have implemented measures such as vessel monitoring systems, satellite tracking, and onboard surveillance to deter and detect illegal fishing activities. These technologies enable authorities to identify suspicious behavior and take immediate action against offenders.

Furthermore, international collaborations between countries have proven to be essential in combating IUU fishing. Through regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) and multilateral agreements, nations are coordinating their efforts to address illegal fishing in shared waters. These partnerships foster information sharing, joint surveillance operations, and data analysis, resulting in better enforcement and a more robust system to combat IUU fishing across borders.

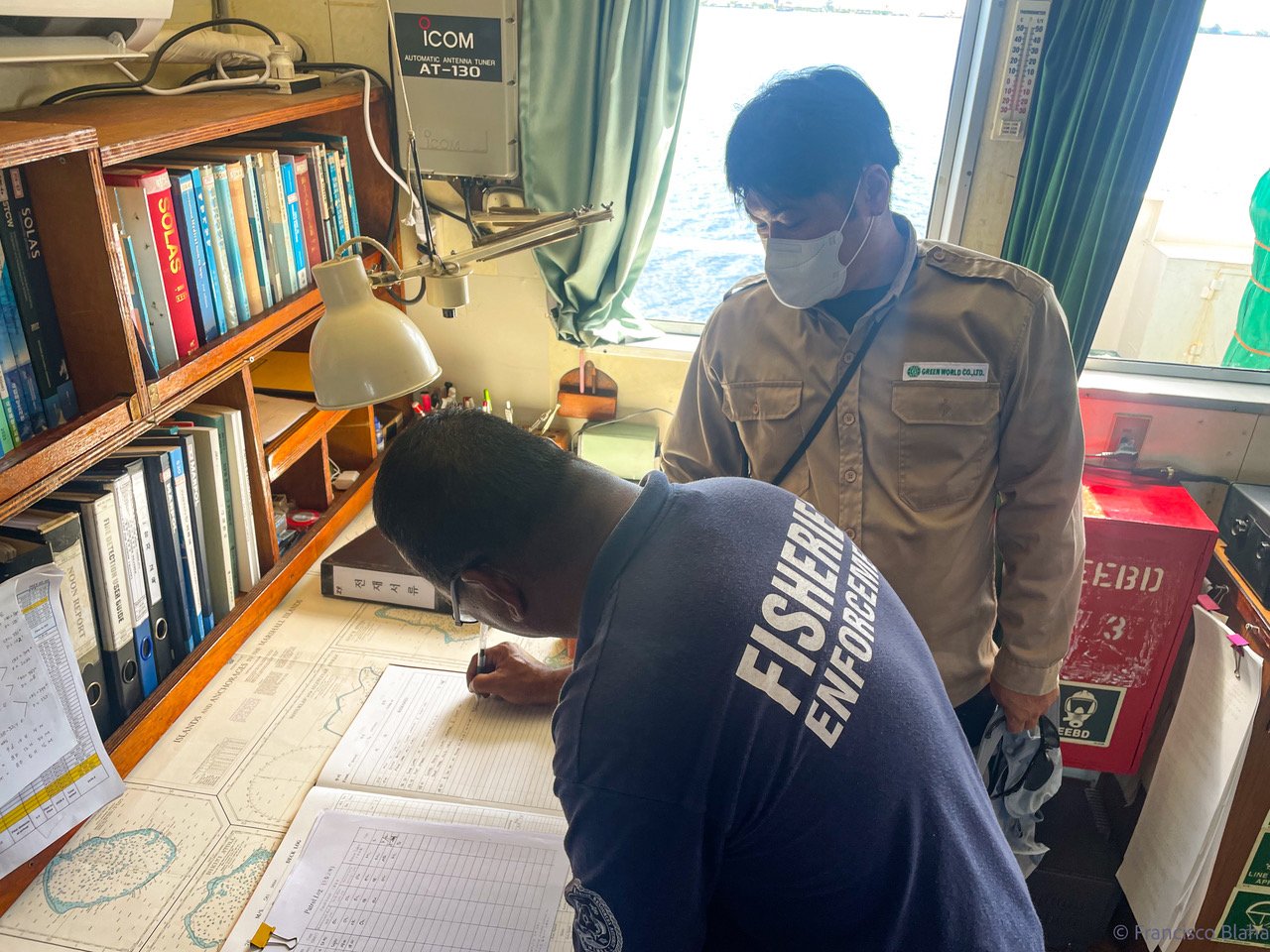

Strengthening port controls has also become a critical component in combating IUU fishing. Implementing strict inspection measures at ports ensures that seafood products entering the market are legally caught, reported, and regulated. By conducting thorough inspections and verifying the authenticity of catch documentation, authorities can prevent illegally acquired fish from reaching the market and disincentivize offenders.

Raising public awareness is another essential aspect of combating IUU fishing. Educating consumers and urging them to make sustainable seafood choices can significantly impact market demand. By supporting well-managed fisheries and certifying sustainable seafood products through reputable organizations, consumers play a vital role in incentivizing legal fishing practices and discouraging IUU activities.

Moreover, empowering local communities in fishing areas is key to combating IUU fishing. Many illicit fishing operations occur in regions where poverty and lack of alternative livelihoods prevail. By investing in education, infrastructure, and sustainable economic development, we can offer affected communities the opportunity to pursue legal and sustainable fishing practices, reducing the incentives for IUU activities.

In conclusion, combating IUU fishing requires a multi-faceted approach that involves the collaborative efforts of governments, international organizations, local communities, and consumers. Stricter regulations, international cooperation, robust port controls, public awareness, and community empowerment

Are Fisheries Ecolabels any good?

Fisheries ecolabels have gained popularity in recent years as a tool to promote sustainable fishing practices. These labels, often awarded by independent certification bodies, aim to inform consumers about the environmental impact of the seafood they purchase. While the intention behind fisheries ecolabels is commendable, their efficacy and overall impact remain subject to debate.

One of the key arguments in favor of fisheries ecolabels is that they provide consumers with transparent information about the sustainability of the seafood they buy. By displaying a recognizable ecolabel on their product, fisheries can communicate their adherence to certain environmental standards. This may influence consumer behavior and encourage the demand for sustainably sourced fish, thus incentivizing responsible fishing practices.

Proponents also argue that the certification process behind fisheries ecolabels encourages fisheries to assess and improve their sustainability practices. In order to obtain an ecolabel, fisheries must meet specific criteria established by the certification body. This raises awareness within the industry about the need for sustainable management and can encourage positive change in fishing practices.

However, critics question the effectiveness of fisheries ecolabels in achieving genuine sustainable outcomes. Some argue that the criteria for certification may not be stringent enough, resulting in cases where ecolabeled products do not meet consumers' expectations in terms of sustainability. This can erode consumer trust in the credibility of ecolabels and undermine their intended purpose.

Moreover, fisheries ecolabels often focus primarily on the environmental aspects of fishing, potentially overlooking other critical factors. They may not adequately address social and economic aspects, such as labor rights, fair wages, or the impacts on local communities. True sustainability ought to encompass a holistic approach that considers the entire ecosystem, as well as the well-being of people involved in the fishing industry.

Another significant concern is the potential for "greenwashing" – the act of giving a misleading impression of environmental responsibility. Some fisheries might view obtaining an ecolabel as a marketing opportunity rather than a genuine commitment to sustainability. If certification bodies do not rigorously evaluate and monitor the certified fisheries, the ecolabel could lose credibility and become merely a marketing gimmick.

In conclusion, fisheries ecolabels have the potential to play a positive role in promoting sustainable fishing practices. They allow consumers to make informed choices and can drive positive change within the industry. However, the effectiveness of these labels is dependent on robust certification criteria, transparent auditing practices, and a holistic approach to sustainability.