I have written ad nauseam on HS transhipment in the WCPFC and abuse of the impracticability exemption. I also proposed some solutions, and I’m working on the deck in the intercessional working group for transhipment reform at the WCPFC.

In principle, it should not be too hard to fix, really… is only a small group of countries doing it, and they are the same across all oceans.

This new study by my colleague Gohar Petrossian and colleagues (based on her prior work) for PEW does illustrate it again… and again…

Read the original, here are some brief quotes

Flag trends

The study found that most carrier vessels were flagged to just a few countries: Panama (54% of key carriers); Taiwan, Province of China (10%); China (9%); and Liberia (5%). When looking at relationships between flags, Panamanian-flagged carrier vessels had the largest number, 2,082, of encounters with fishing vessels flagged to China, accounting for 24% of all detected transshipments. (See Figure 2.) Carrier and fishing vessels both flagged to Taiwan had the second-strongest connection at 1,109 encounters, or 13% of all transshipments.

Several countries, including Panama, allow foreign-owned or -controlled vessels to register under their flag through an “open registry.” In recent years, several countries have highlighted issues regarding Panama’s monitoring and control of its registered vessels. For example, in December 2019 the European Union issued a second formal warning to Panama because of the country’s persistent failures to meet its obligations to fight illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. And the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recorded several violations by Panamanian-flagged vessels in its 2019 and 2021 biennial reports to Congress.

Global transshipping networks

The study identified 12 distinct networks or “communities” of key carriers and estimated their relative importance and contribution to the overall global network. Five of those communities, which the research team referred to as A, B, C, D and E, collectively accounted for 65% of all activities, with the top three communities (A, B and C) conducting almost half (49%) of global transshipment. Not surprisingly, given the analysis’s focus on RFMOs that oversee tuna and squid fisheries, four of the top five communities were largely associated with tuna and tuna-like fisheries and the fifth was probably associated with squid fisheries.

Community A

The top community included 23 key carriers—mostly flagged to Panama and Liberia—that conducted nearly a quarter (22.7%) of the transshipment events examined. Community A’s transshipment activity spanned multiple ocean basins and RFMO management boundaries, with noticeable hot spots in the Western and Eastern Central Pacific regions, Indian Ocean, Southeast Atlantic and the Eastern Central Atlantic, as well as near the EEZs of the West African coast.

Community B

This group of 12 key carriers, flagged to Taiwan and Panama, engaged in the second-highest proportion of transshipment events (14.7%), primarily in the Western Indian Ocean and Western Pacific.

Community C

This group, which accounted for 11.4% of the activities and contained five key carriers, showed low overall geographic spread, with transshipment events concentrated in the southeast Pacific region and just outside the EEZs of French Polynesia and Pitcairn Islands.

Community D

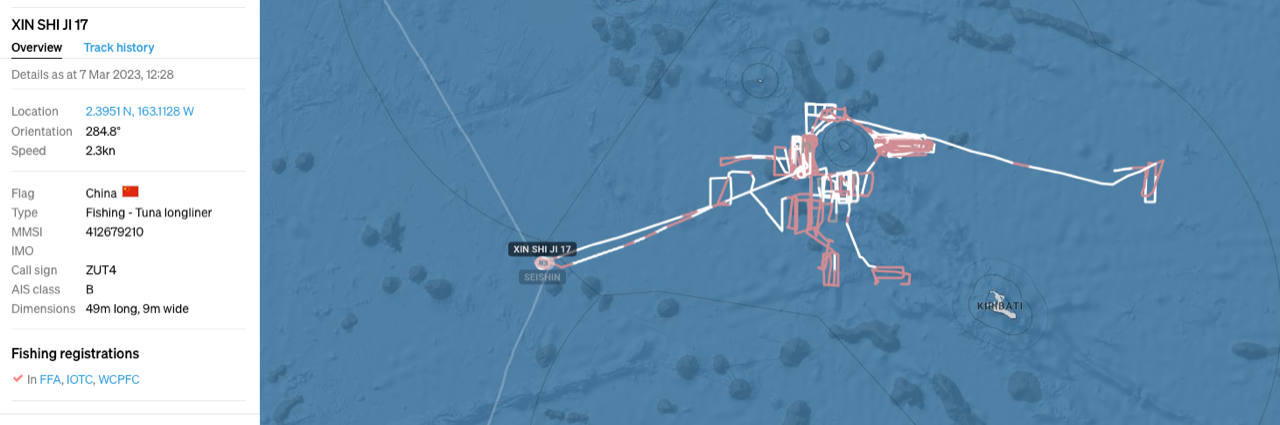

Like Community A, Community D’s encounters, which made up 8.2% of activities and involved eight key carriers, were spread across the Western and Eastern Central Pacific regions—mainly the equatorial Pacific. However, unlike the other communities, this group conducted significant activity immediately outside of several EEZs, including those of the Solomon Islands, Nauru, Tuvalu, Kiribati, Tokelau and French Polynesia. (these are my focus see one example below of the many I have)

is not doing nothing “ilegal” but where is the impracticability of hamering the costal waters of Fanning (always outside the 12nm) and then after being fishing near kiritimiati (a official port) and doing over 200 to tranship in 4 nm of the EEZ, instead of doing less than 100 to Kiritimati… inpracticability yeah right…

Community E

The 19 key carriers in Community E mainly engaged with Panama-flagged fishing vessels. This community operated in a wide geographic area with hot spots in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and high seas areas close to the EEZs of Russia, Peru and Argentina, which are associated with productive squid fisheries.

Conclusion

By identifying the key carriers and the vessel communities of which they are a part, this study sheds light on the global reach of these carriers and the true scale of the transshipment network. These findings, in turn, highlight the need for better coordination among countries, businesses and market stakeholders, especially for oversight of activities on the high seas. To effectively manage increasing transshipment activities, stronger regulatory frameworks are needed oceanwide to ensure that vessels are operating within legal requirements and illegal catch does not reach the marketplace.

Obviously, I agree with these points…and I think that we around all initiatives have to act in a pack and puch from all corners... add requirements for EM for TS in HS, and add observers.... since the present scenario is not functioning...

We should also push for an independent observer programme, here is what I wrote for PEW last year (summary already lodged here https://www.wcpfc.int/file/672477/download... ) this could make the TS at sea very expensive and such push the vessels to come over to port at a reduced rate.... look at the fees that IATTC observer earns (340USD/day) and the ones agreed to that and paying it are China, Japan, Korea, Panama, Chinese Taipei, Vanuatu... and this is one way less profitable fishery than the WCPFC… so coming to port should be cheaper

this is gonna be a loooooong swim in rough waters… when it shouldn’t be