This blog post has been brewing for a while and is about a paper published recently…. There are two factors to it.. 1) it deals directly with a key component of my work, and 2) the lead author is a friend and mentor!

I got to know Blaise back in Tonga in 1998 when he was starting his career at FAO, and I was on my 1st consultant job getting over my impostor syndrome from coming to work as an FAO consultant with people and boats I was fishing with 3 years before!

In any case, I think the liking was mutual, and we have always stayed in contact since then, he has always been incredibly generous with his advice on professional and personal matters, and I have been lucky to work with him on PSM issues back in his home country PNG and a few more after that.

Besides being incredibly capable, his best quality (at least in my opinion) is very simple to define; he is a “gutpela man” (good person, kind and thoughtful) in Tok Pisin.

The topic of the most recent paper he was the main author says it all in the title: “Enforcement approaches against illegal fishing in national fisheries legislation.” This topic is pertinent for me since my work on MCS is delimited by the strength and extent of the legislative framework that covers it. In my past life as a compliance guy with the industry, I used my mantra of “how can you regulate what you don't understand” to my client's advantage when things went to court, and my role in finding holes and technical inconsistencies in prosecution cases… not that I’m proud of it…. But I see worst with really powerful accountancy firms that make corporate clients pay lesser proportionate tax than a teacher…

In any case, the reality is that soon as things get into court, everything takes time, and it gets VERY expensive… so it is much better to settle outside court…

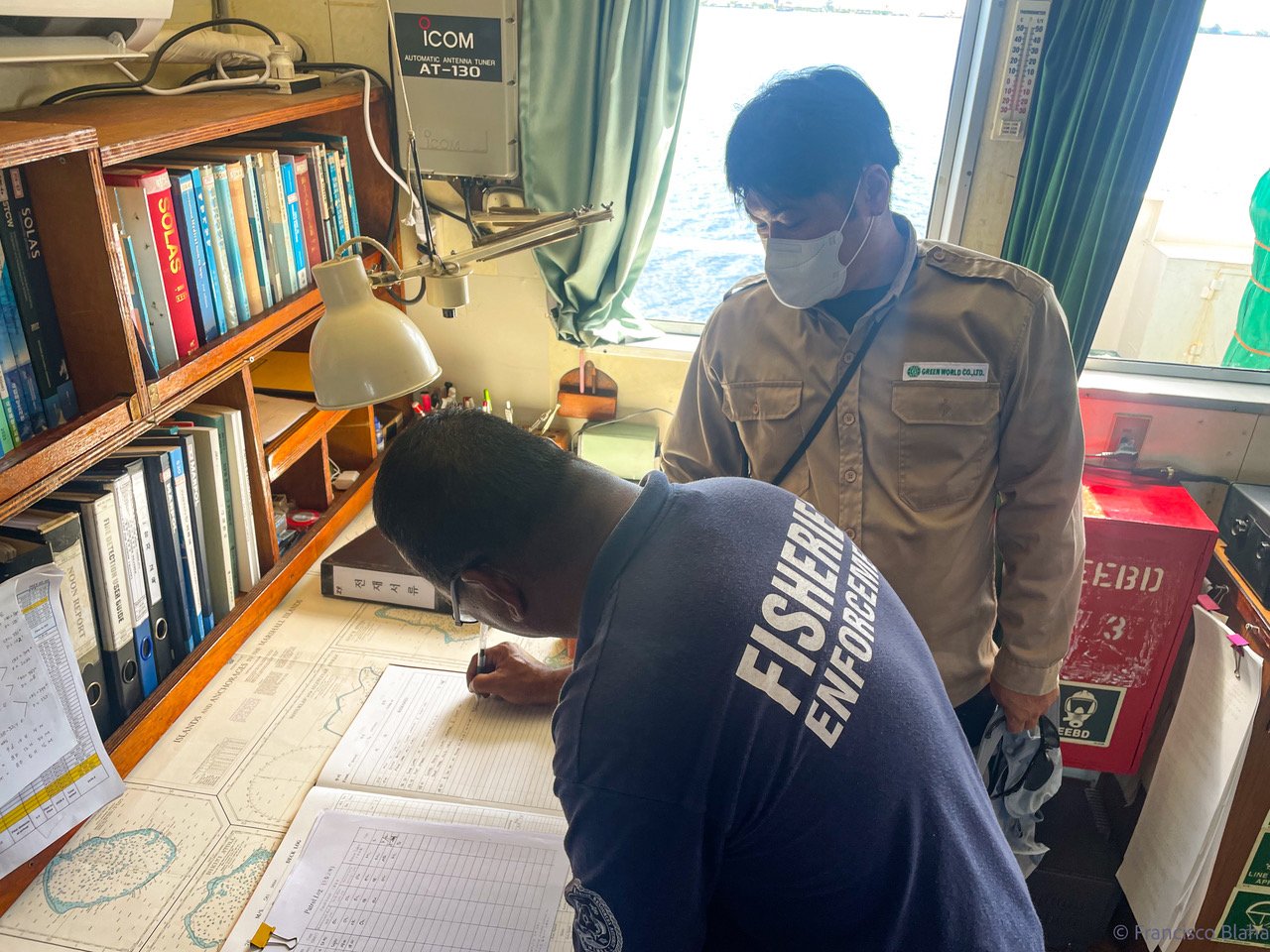

Yet, for this to be an option, the case you build and the evidence has to be so irrefutable that it is cheaper for the vessel owner to cut their losses and get on with stuff. And here is where I focus a lot of my work on mentoring.. where to find and secure irrefutable evidence on board fishing vessels… which normally is beyond the documents the skipper presents.

For us in MIMRA, this has worked very well; in none of the 5 cases we brought to our legal counsel through the implementation of our PSM procedures was pursued into the court system. The vessels’ owners realised that is was better to settle since the cases were waterproof (pun intended). Here are the public details of one of these cases.

Blaise and co-authors explore a few overarching questions underpinning the scholarly debate on illegal fishing and crimes in the fisheries sector.

First, whether criminalising illegal fishing or subjecting such fishing to criminal law processes leads to better compliance with fisheries legislation or is a more effective approach to tackling illegal fishing. Second, whether the problem of illegal fishing persists due to the lack of its criminalisation or the resistance by States to criminalising illegal fishing activities.

They analyse the primary fisheries legislation of States and the EU to understand better the enforcement approaches adopted therein, the responses used to empower national authorities, establish processes, delineate liability, and fix the sanction scheme, including the level of sanctions in terms of severity for illegal fishing.

They ultimately aim to demonstrate that the options used to combat illegal fishing set out in national fisheries legislation are not limited to a single type of enforcement approach.

Indeed, their assessment of national fisheries legislation shows that most States seem to follow a dual enforcement approach, which includes provisions enabling the use of both administrative and criminal processes and sanctions to enforce against illegal fishing and fishing-related activities.

They rightly support a multipronged approach to address illegal fishing, which may include legal solutions such as criminalising serious fisheries violations.

As usual, I recommend you read the original, as it also dwells on the role of regional organisations, especially FFA.

I just quite the conclusion here below:

The ‘most appropriate’ legal strategy to tackle illegal fishing through regulatory frameworks does not rely on and should not depend upon the law-maker’s emphasis on a particular enforcement approach, whether administrative, civil or criminal. As seen in this assessment, most States endorse a dual enforcement approach in their primary fisheries legislation with respect to the authority competent for processing fisheries offences, the respective process, applicable liability and sanctions for illegal fishing. The findings reveal that most countries have employed both administrative and criminal processes and sanctions to combat illegal fishing in their primary fisheries legislation. Hence, there is no single solution, at least in terms of what the national fisheries legislation by foreign fishers should provide for, with a view to tackling illegal fishing. It is not by purely focusing on management and MCS provisions, or in solely establishing rigorous processes and severe penalties of criminal sanctions and years of imprisonment that States can combat illegal fishing.

A vital consideration for ensuring that the primary fisheries legislation of a country is robust in facilitating effective enforcement to tackle illegal fishing is that the relevant laws take advantage of the most efficient and practical enforcement options made available by the countries’ legal system and practice. At the same time, the fisheries legal framework must implement and be consistent with relevant international and regional instruments and standards. Notably, in accordance with the LOSC, national legislation of concerned States must include a provision on prompt release of the arrested foreign vessel and crew (Article 73(2), LOSC) and must not impose, for the violation of fisheries legislation, the penalty of imprisonment and any other form of corporal punishment in their respective EEZs, unless otherwise agreed by the concerned States (Article 73(3), LOSC). The procedure of prompt release is separate from, not incidental to or prejudicial to the coastal State’s judicial or administrative proceeding (on the merits) against the vessel and crew for the violation of its fisheries laws .

Due to the complex nature of illegal fishing, the solution for this persisting global problem in fisheries seems to require a multipronged approach targeting different facets of the problem. The actions and thinking promoted by legal scholars and international organizations is that combatting illegal fishing and crimes in the fisheries sector should not be limited or restricted to a single enforcement approach and softening the actions against illegal fishing, especially when it is accompanied by transnational organized crime dimensions. Irrespective of whether a country has established and emphasises an administrative/civil and/or criminal processes to enforce fisheries legislation, it is important that in applying the existing framework, States are attentive to the particularities of the fisheries context, especially with respect to the special needs of small-scale fisheries.

We submit that illegal fishing activities that involve elements of transnational organized crime should be considered a serious violation (or a serious crime), which should consequently attract congruent enforcement action. Indeed, members of the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) have enjoyed relative success by treating illegal fishing as a serious matter regardless of whether administrative or criminal enforcement is used. The imposition of severe penalties for illegal fishing and the overall reduction in IUU fishing in the FFA region is a result of a combination of efforts, actions and approaches, including: building knowledge; revising legislation to ensure better MCS (through e.g., evidentiary provisions, higher penalties and forfeiture of vessels); raising awareness and education (stakeholders, enforcement officers, parliamentarians, judges) to change public and judiciary perception so that illegal fishing is considered a serious crime.

Steps towards recognising illegal fishing as a serious violation deserving severe penalties, as noted above, include: associating it with crimes in the fisheries sector and other aggravating aspects such as the harm it causes to ecosystems and the environment; considering its transnational nature; treating it as a crime against humanity; or treating it as a serious crime where organised criminal groups are involved in such fishing. In addition to these options, Lindley and Techera draw attention to the lack of synergies in the operation of the international community’s toolkit essential to address illegal fishing, suggesting a ‘regulatory pluralism approach’ and the need to put in place a ‘collaborative global body charged with bringing the instruments and actors’ together. Indeed, most scholars point to the importance of examining, interpreting and applying various fields of law relating to illegal fishing, and the concomitant and coordinated efforts from the respective institutions and stakeholders to address the problem.

Our message is essentially the same, noting that, as regards national fisheries legislation, both criminal and administrative or civil enforcement approaches could be adopted by States, in line with State legislative practice.

At the international level, inter-agency collaboration particularly through the FAO and UNODC, has advanced the work in clarifying the linkages, challenges and legal responses to crimes in the fisheries sector. We add to this initiative by having demonstrated how States have approached enforcement to address illegal fishing in national fisheries legislation and emphasising how to build on that. Our findings show that the use of criminal proceedings to tackle illegal fishing are not any close to an innovation in States’ legislative practice, nor could such practice be considered insufficient by lack of criminalization of illegal fishing activities. Criminal proceedings are already in place and appear to have not been used effectively enough by States to tackle illegal fishing. This needs to change, commencing with viewing certain illegal fishing as a serious violation warranting adequate and sustained enforcement effort leading to the imposition of severe penalties to have the desired deterrent impact.