Over the last few years, we have seen a valid focus on Port State Measures, and area I work a lot on its planning and operational aspects. This was all strengthened in 2009 with FAO’s PSMA, which has been gaining strength, particularly after its implementation.

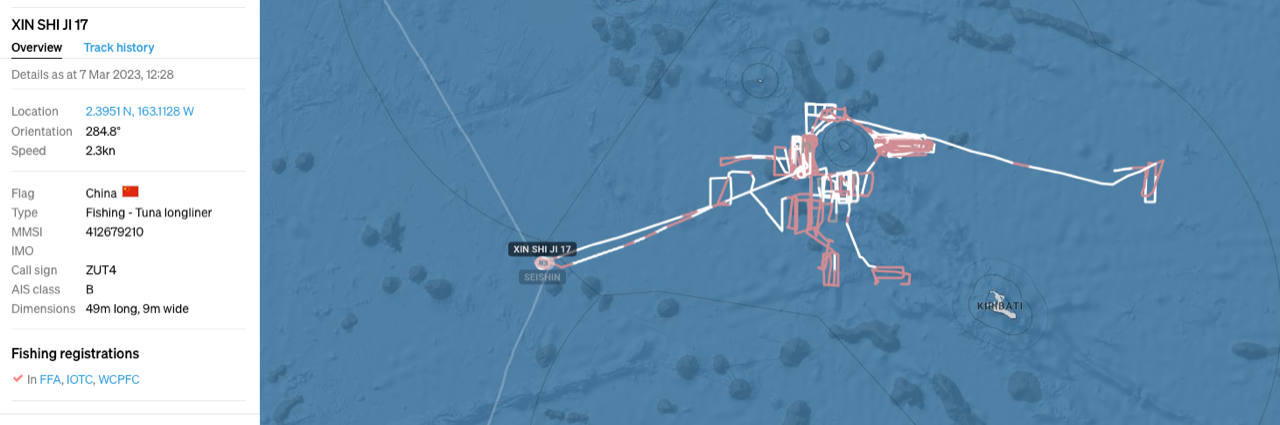

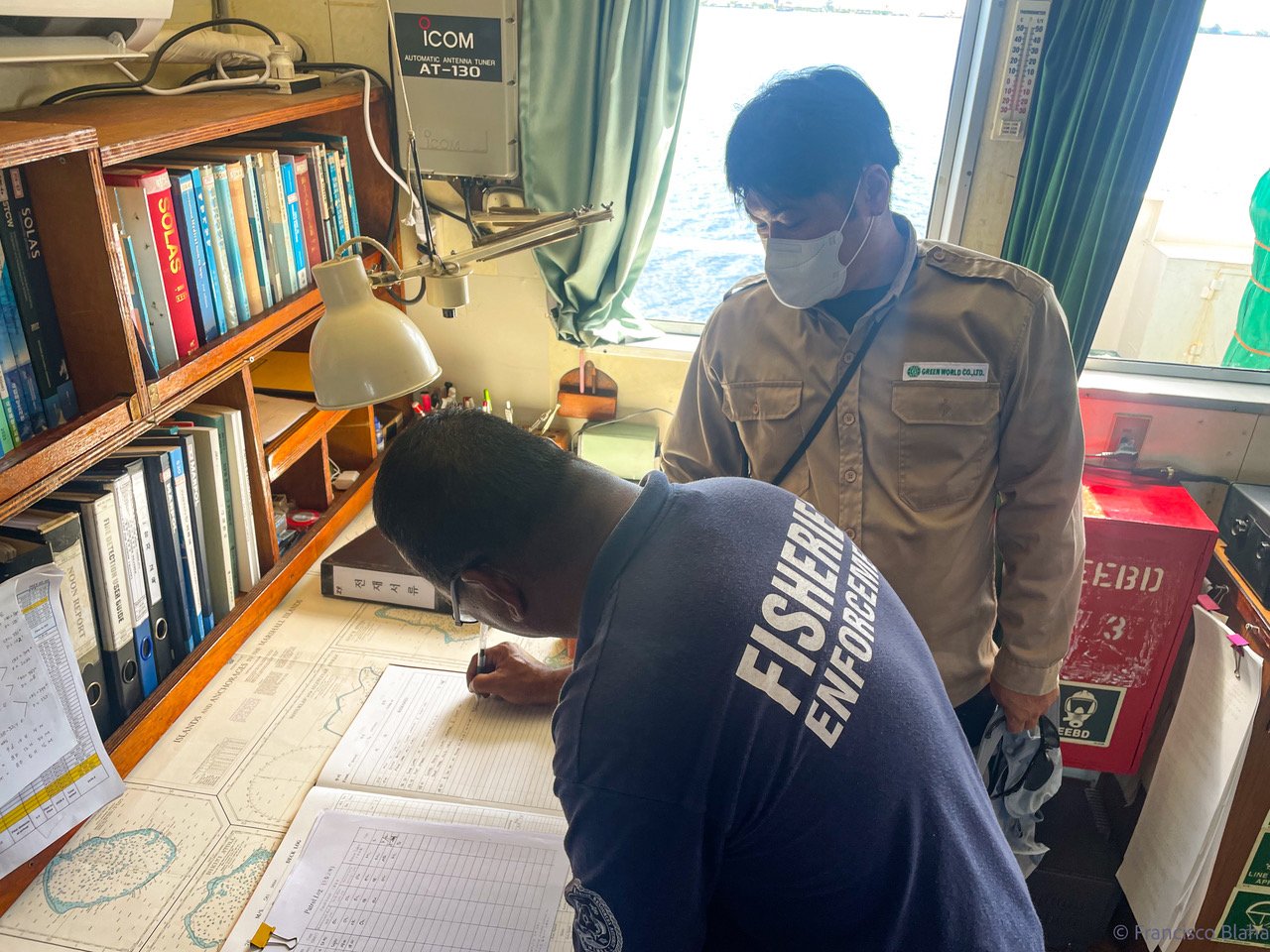

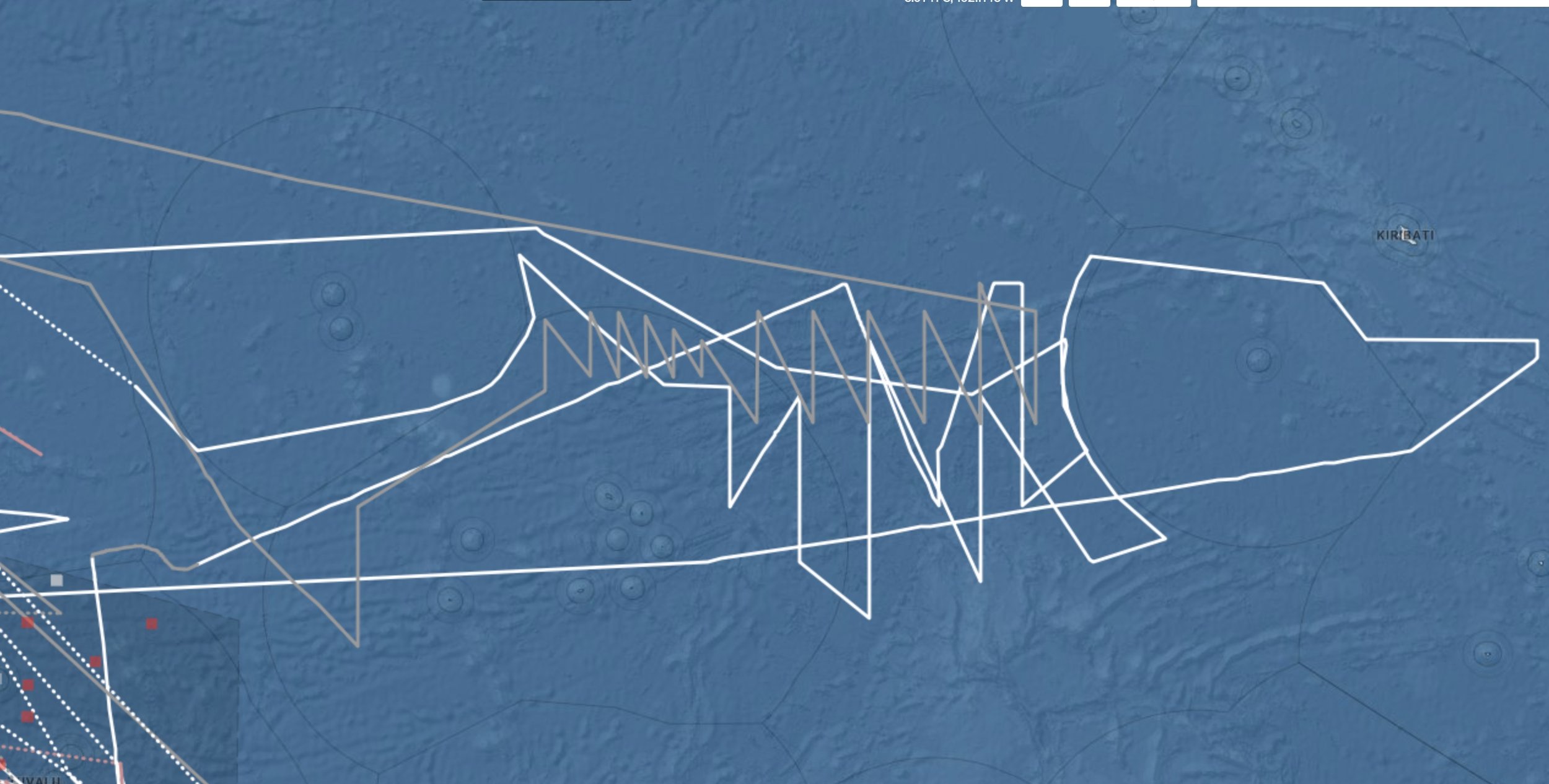

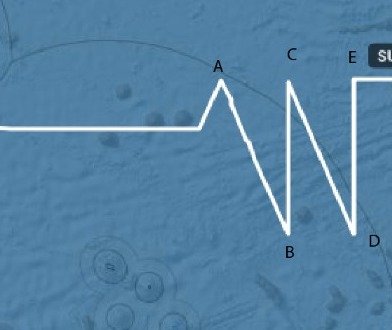

And while I’m always cautious to stress that signing an agreement is not implementing it and that you can be doing excellent PSM without having signed the treaty. As a key tuna port in the world, we here in Majuro have focused a lot of effort on it. Every incoming fishing vessel (including RMI flagged) goes through a risk assessment that creates the Arriving Vessel Intelligence Report (AVIR). The intelligence analysis and risk determination allow for the identification of risks in three different categories corresponding to three steps in the analysis, including (i) identity – whether the vessel is who it says it is, (ii) manoeuvring – the vessel’s activity and operations and whether these were adequately reported, and (iii) licensing – whether the vessel is allowed to be in the location it was. The risk analysis performed by MIMRA is focused on fishing vessels to assess the legality of the catch and on carriers' activities not directly related to transhipments.

But it really pisses me off that we are actually, and to a large extent, taking on something that Flag states should be doing! How is it up to us to inspect and authorise vessel unloading when the flag state has access to the same tools we have(or more), and they do not do it…

UNCLOS is clear in article 94: Duties of the Flag State. Every State shall effectively exercise its jurisdiction and control in administrative, technical and social matters over ships flying its flag, furthermore flag State responsibilities extend into Articles 58.3 (rights and duties of other states in the EEZ), 62.4 (utilisation of living resources of the EEZ), and 192 (general obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment).

And if that wasn't enough, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea delivered in 2015 its Advisory Opinion regarding IUU fishing activities.

The Tribunal distinguished the flag State’s responsibility under UNCLOS from its liability.

The flag State, in fulfilment of its obligation to effectively exercise jurisdiction and control in administrative matters under article 94 of the Convention, has the obligation to adopt the necessary administrative measures to ensure that fishing vessels flying its flag are not involved in activities in the exclusive economic zones of other Member States…. The foregoing obligations are obligations of “due diligence”.

With respect to liability, the Tribunal declared that the liability of the flag State does not arise from a failure of vessels flying its flag to comply with the applicable laws and regulations because “the violation of such laws and regulations by vessels is not per se attributable to the flag State” (¶ 146).

Instead, the liability of the flag State arises from its failure to comply with its own “due diligence” obligations. Thus, the flag State will not be liable if it has taken “all necessary and appropriate measures to meet its ‘due diligence obligations” to ensure that vessels flying its flag do not conduct IUU fishing activities in the EEZ of the coastal States.

So if we, as a developing country port state, exercise sufficient due diligence to evaluate the activities of foreign vessels, it should be to validate and strengthen the fag state due diligence, not to take responsibility on their failings as it is now! These are your vessels; how come you don't authorise unloading based on checking on the compliance of their fishing trips, independently from where they are!

I already hear them saying… but we have hundreds of vessels fishing worldwide… we cannot control them all…. Well, sorry, but that does not exempt you from your responsibilities… if they cannot control each one of these fishing beyond your EEZ, they should not licence them to leave. Or directly, they should not flag them if they don't have the means to be responsible for them as required by international law.

Back in 2017, in the traceability for fisheries compliance book we wrote for FAO we identified what are the ideal Flag state configuration; we recommend that there needs to be some form of flag State authorisation of the unloading.

And in the recent “Advancing end-to-end traceability along capture fisheries and aquaculture value chains” , we also identify Unloading (transhipment at sea, in port or landing, or any combination thereof) where Flag state best practices request vessels to seek to unload authorization from the flag state (independent of port entry or transhipment at sea).

And I will stake it a step further when it comes to transhipments in the HS, and it should be the role of the flag state of that carrier to do an analysis similar to the one we do in Port States before authorising the reception of fish... they have access to the same tools we have… this is essential “due diligence” and equivalent measures.

I’m starting to get unnerved by the present trend of having ports in countries that have not signed to PSMA qualified as “Port of Convenience” regardless of whether they implement PSM or not… Signing a piece of paper does not make you compliant! We in RMI have not signed yet, but we comply with every aspect of PSM; we even publish our PSM system online, something I have not seen many (if any) PSMA signatories do.

While in the meantime, flags state (many from well-off developed DWFN) keep ignoring their responsibilities and obligations of due diligence as recognised in international law.

My solution for this? Have an independent body set up by FAO COFI to evaluate flag state performance (perhaps using a version of this one prepared by PEW?) that accesses their compliance and has trade tariffs proportional to the level of compliance… the better a country is, the lesser tariff it pays.

In my experience, you have no incentive to change if it does not hurt your pocket.