Every year just before the plenary meeting of the WCPFC (this year in Vietnam), the most important publication (at least in my view) of the tuna world gets published by SPC: The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2021 Overview and status of stocks was just released.

Besides the importance of the information, I got the kick to see one of my pictures for the 2nd time on the cover, something I’m honoured for and forever thankful to the SPC team and Steven Hare in particular.

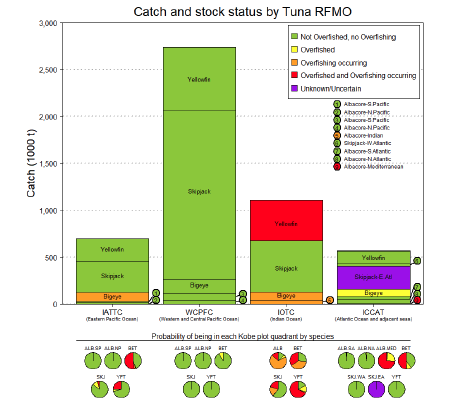

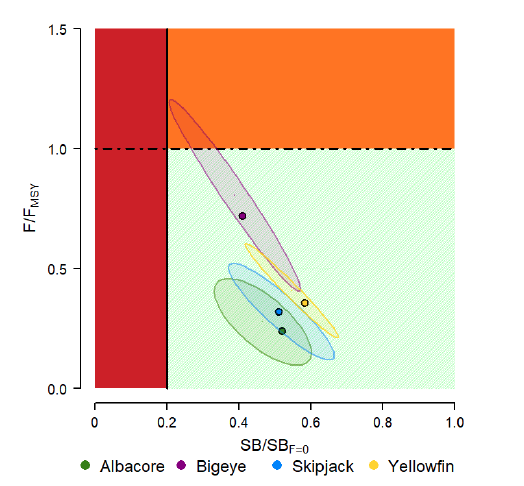

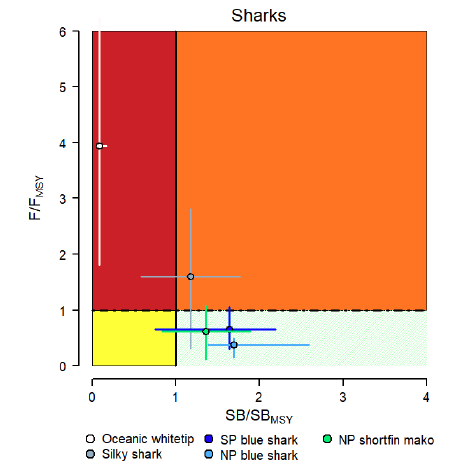

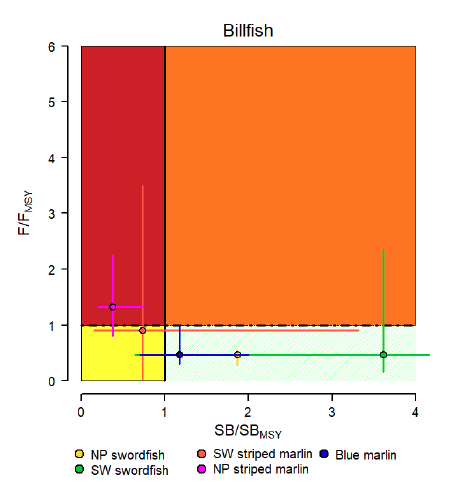

The publication is a cornucopia of information and an honest appraisal of what is going well (the status of the main 4 stocks - page 52) and what is not (the status of some sharks and billfishes - page 58).

So, I recommend you read it and dive deep into the many excellent graphs.

And while there is a lot to celebrate, I’ll lo bring back something that I already noticed in last year's edition and bring it up again now, and it is related to the longline fleet.

As I stated before, I really like the technicalities and challenges of LL fishing, is perhaps the most skilful and “scientific” of fishing gear I fished with. You need to understand and play with depth, currents, thermocline, primary productivity/temperature, target species chemoreceptors, length and spacing of branchlines, catch manipulation and quality, freezing physics and many more elements…

And while I have no issues with the domestic and EEZ-based operations, yet the High Seas fleet is a total mess.

As I pointed out last time, the fishery has been declining in volumes and number of vessels over the years, but a more direct measure of effort (hooks fished) has shown a different trend. Total hooks fished in the WCPFC-CA increased from a level of 400 million in the mid 1970s to 600 million in the early 2000s to 800 million in the early 2010s. The peak year in hooks fished was 2012 at 888 million hooks; the level in 2021 was 612 million hooks, a decline of 12% from the 2020 level, and nearly 16% below the average of the previous five years.

What is driving this (in my opinion), relates to a few things but I have, I have touched on two aspects many times in the past, HS transhipments + the abuse of the impracticability exemption and crewing labour issues.

And for me, this graph below (page 42) is indirect proof of the linkages of both.

You see fishing effort, in fleet sizes and number of hooks fished (bottom), for the longline fishery in the WCPFC

In the 1993/4 when I was fishing these waters, it was the heyday of LL in the WCPO, peaking into 5000 vessels. Today as you can see, there is only 1/3 of that fleet left (1600), yet they are soaking almost twice the number of hooks. How can that be possible? Deck and gear setting technology are almost the same.

Since then, transhipment at sea has exploded (as I reported many times*), which allows the vessels to stay fishing longer and, sadly, massivelly increasing the crew's workload.

This strengthens my focus on the two inter-seasonal working groups I’m involved in at the WCPFC, transhipment reform and labour conditions.

* Reported high seas transshipment events in the WCPO have more than doubled from 2011 to 2019. In 2021, 62% of vessels listed on the Record of Fishing Vessels were authorized to transship in the high seas, 85% of which are longliners