Written ad nauseum about it… yet make it clear that while we have a CMM that prohibits transhipments at sea (and works for all Purse seiners) yet for LL does leave a massive loophole that has been absolutely abused… CMM 2009-06 states that “to the extent practicable, transhipment must be conducted in ports”,… yet what is practical has not been defined (i wrote about it here)

I’ll say that 90% of the FFA members have voiced a preference for a prohibition on all at-sea transshipments, as per the initial text in CMM 2009-06, but, as the practice remains authorized, there is a range of practical reforms available to improve transhipment oversight, especially through observer reporting. As CMM 2009-06 establishes terms and conditions for transshipments in areas beyond national jurisdiction, including the required reporting and the prerequisite for an observer to monitor and verify high seas transshipments, but n practice, very few, if any, observer reports have made their way to the WCPFC, meaning the capacity to independently validate vessel reports remains very limited.

As you imagine, all chances to reform the present transhipment practice, if not bluntly opposed, are drag and watered down by the nations in the WCPFC that are responsible for all the HS transhipments ( (China, Korea, Taiwan, Vanuatu, Japan and Panama)

And we know is a massive and hypocritical loophole… In two recent FFA studies (2016 and 2020) I was involved on the “Quantification of IUU Fishing in the Pacific Islands Region”, highlighted at-sea transhipment in HS as a key area of uncertainty in the longline supply chain. The most recent update- (2020) stated that “important areas of uncertainty remain in the at-sea transhipment component of the longline supply chain and monitoring and control remain a work in progress. In particular, improvements are required to strengthen the implementation of the observer program such that information provided by vessels on the volume and species composition of fish transshipped can be validated against independent observer estimates”.

My last blog was of the hypocrisy of the situation, particularly when you see the immense majority of the transshipments reported on the borders (mile 2001) of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), rather than in the most isolated areas of the high seas – which is where in port transhipment may be considered impractical.

In the past I noted that the WCPFC is the only tuna RFMO (tRFMO) that does not mandate a specific High Seas transhipment observer program for receiving carriers.

Some WCPFC members do mandate observer coverage on their flagged vessels under their national observer program but not under a wider transhipment-specific WCPFC scheme. In addition, there are currently no WCPFC requirements for, or definition of, useful monitoring information for transshipments by observers. And, since WCPFC’s PSMs CMM 2017-02 includes an opt-in mechanism and requires members to specifically request inspections in port, these carriers are unlikely to be afforded the necessary oversight once they enter the final destination port with transshipped product on board. This current process does not provide consistent information conducive to the long-term conservation and sustainable use of tuna resources in the region – a stated aim of the Commission[DBC1] [FB2] .

And while there have been some efforts to standardize transhipment observer training, such as the Pacific Islands Regional Fisheries Observer (PIRFO) Training Framework, where micro-qualifications are “completed in addition to the mandatory units of competency of a full qualification”.

Furthermore, under a contract with FFA’s a couple of years ago, we wrote the competency standards for transhipment observers that meet the criteria for being considered as a micro-qualification and, in due course, should be submitted as a learning unit for accreditation on the Pacific Register for Qualifications and Standards (PRQS) under Educational Quality and Assessment Programme (EQAP). This would be a critical first step toward consistent transhipment observer reporting… yet without the support of all members… ain’t going far.

There is the perception that having a specific and independent observer programme can be seen as a tacit endorsement of HS transhipment, and while there is definitely merit in that opinion, I like to see it as a practical measure to put pressure (and costs) on transhipping nations, since the reality is that at the moment, we have the worst of all possible situations, no capacity to stop them, nor an independent and effective way to capture the data generated there.

So I was asked to develop an information paper on approaches that improve data collection of the practice and provide a summary of estimated costs and management of observer program management at the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), Internal Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA).

The analysis is so far not relesed oficially; I just resume the most important bits down below.

High Seas Transshipment Observer Reporting at Other Tuna RFMOs

Other tRFMOs such as Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and to a certain extent the Secretariat of the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) have similar transshipment measures in place which apply to large-scale tuna longline fishing vessels and authorized carrier vessels. Each measure requires that:

All at-sea transshipments are prohibited unless monitored under the transshipment ROP.

Members ensure that all carrier vessels have a transshipment ROP observer onboard

Members submit annually a comprehensive report assessing the content and conclusions of the reports of the observers assigned to their carrier vessels.

These measures have led to very similar high seas transshipment Regional Observer Programs (ROP) managed and administered by an independent organization across these tRFMOs. The third parties have provided training, coordinated placements, debriefed observers, and reported on transshipment data for over a decade. The implementation of the transshipment observer program is financed by the countries whose longline vessels wish to engage in transshipment operations.

1. IOTC

Currently managed under Resolution 21/02[1], at sea transshipments observer program in the IOTC area have been managed by the Consortium of Marine Resource Assessment Group (MRAG) and Capricorn Fisheries (Capfish) since 2008. Like ICCAT and IATTC, the responsibilities of the Consortium include the training and provision of qualified observers, managing the logistics for the deployment of observers and their repatriation at the end of the deployment and maintaining the IOTC at-sea transshipment program database. A report for each deployment is also submitted to the IOTC Secretariat at the end of each deployment. In line with the agreed confidentiality rules, these reports are subsequently edited by the IOTC Secretariat and forwarded to the concerned fleets whose vessels have transshipped under the deployment for which the report covers. Additionally, the reports for deployments where Southern Bluefin tuna (SBT) have been transshipped are also forwarded to CCSBT, as per the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed between the IOTC and CCSBT. This arrangement has the benefit of minimizing costs to the fleets that catches and transships SBT in the IOTC Area.[i]

2. ICCAT

The ICCAT regional observer program for at-sea transshipments is carried out under the provisions of the Recommendation 21-15 on transshipment. The ICCAT transshipment observer program has been implemented by a consortium comprising of MRAG and CapFish since 2007. This contract provides carrier observer training and annual reports detailing transshipment information and summarizing observer reports from the previous year in addition to equipment purchases and observer deployments under the supervision of the Secretariat.[ii]

3. IATTC

IATTC’s transshipment measure - Resolution C-12-07 – also limits at sea transshipment to longline and carrier vessels whose flag countries participate in the program to monitor transshipments at sea. MRAG Americas has been implementing the IATTC ROP since its inception in January 2009; providing similar services outlined above for ICCAT and IOTC. MRAG records and verifies positions of vessels engaged in transshipments to issue daily reports on activities and provides captains with the opportunity to include any other relevant information. Under this program, observers also verify and countersign the transshipment declaration forms.[iii]

4. CCSBT - Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna

The CCSBT’s observer program to monitor SBT transshipments at sea which came into effect in 2009 (and later revised in 2015), is regulated under the Resolution on Establishing a Program for Transshipment by Large-Scale Fishing Vessels. CCSBTs transshipment program is operated in conjunction with the ROP for transshipments of ICCAT, IOTC and WCPFC to avoid duplication of the same measures. For this reason, the report will focus on the details for ICCAT, IOTC, and IATTC.[iv]

5. PNA - Parties of the Nauru Agreement

While not a transshipment ROP, a pertinent example of an independent operated observer program in the WCPO is the PNA Observer Agency (POA); this program assumed responsibility for the FSM Arrangement observer program and has been administered under contract by MRAG Asia Pacific Pty Ltd (MRAG AP) since 2012. MRAG was chosen after considering several service options through an open tender process to outsource the administration of the POA to a commercial service provider. The core responsibilities of MRAG AP under their contractual arrangement is operational logistics focused on identifying and coordinating placements for the PNA observers covering 100% for PS vessels authorized to fish in PNA waters. MRAG coordinates observer contracts, finances, and travel arrangements in addition to providing reports to the PNA. Only observers that are nationals of a PNA member country and accredited by the PIRFO program are eligible to be used by the POA.[v]

Considerations for Implementing an Independent Transshipment ROP in WCPFC

A. Precedence

In practice all the flag States, and most of the individual carriers operating in the WCPO have experience with independently run transshipment observer programs. The option of delegating the operational and logistical tasks involved in running an ROP under the arrangements set out in CMM 2018-05 on the WCPFC Regional Observer Program, is not new in the WCPO as it has been in place since 2011 under the PNA observer program. The success of the PNA observer program sets a valuable precedent for the potential development and implementation of a high seas transshipment regional observer program (HS TS ROP). Precedence has also been set by FFA member, Vanuatu, who already operates their own observers on carrier vessels, a model that could be upscaled for a centralized high seas transshipment regional observer program.

B. Observer training

At ICCAT, IATTC and IOTC, observers are required to have at least 1 year of at sea observer experience and submit their CVs to the Secretariat for approval. They then undergo training provided by the consortium as there are no specific standards set by the respective RFMOs. At IATTC for example, the training lasts 5 days and focuses on completing forms, fish identifications, compliance monitoring duties, safety, and communications protocols. For PNA, all observer trainings are provided by PIRFO, and not the POA/MRAG AP, however, where specific observer training (e.g., Marine Stewardship Council Chain of Custody – MSC CoC) is required, this is provided by the PNA Office and supported by MRAG AP[2].

A WCPFC high seas transshipment regional observer program (HS TS ROP) could follow the same processes used by the PNA to recruit trained observers under the PIRFO program (including those who have been qualified by their various domestic programs). Carrier observers an also be tasked to use the WCPFC High Seas Transshipment Electronic Reporting System (TSER) App pre-loaded on tablets and connected to Garmin Inreach units (or its equivalent used by the Pacific Community (SPC)). This will enable carrier observers to send data to the commission and the flag state in almost real time. In addition, the program could incorporate electronic crane scales to improve overall transshipment weight reporting. These transshipment e-scales have been studied and recommended to the WCPFC[vi] and are already informally used at ICCAT and other regions.

C. Observer Cross-certification

ICCAT and IOTC training courses are run in conjunction with one another enabling observers to work in both convention areas and can also monitor CCSBT transshipments. A similar operation might be worth considering for RFMOs neighboring WCPFC, such as IATTC. The 2020 IATTC annual report on transshipment notes that 43 percent of tuna transshipped in the Eastern Pacific Ocean were actually caught in the Western Pacific Ocean[vii] and the 2019 WCPFC Annual Report on Transshipment noted that “high seas transshipment events were reported to have occurred more often in the tropical eastern Pacific, particularly within and around the overlap area with IATTC.”[viii] By standardizing transshipment observer protocols within WCPFC and coordinating with IATTC, both RFMO carriers that operate in both Convention Areas will no longer have to carry two observers, reducing costs and logistical delays. Better coordination can lead to cross-certification of carrier observers[3] (as practiced by ICCAT and IOTC) which could create more opportunities for pacific islanders to be employed on carrier vessels operating in both Convention Areas. Anecdotal information[4] points to some observer preference for carrier vessels over other gear types due to safety, salary, and space considerations.

D. Data reporting and management

IATTC, ICCAT and IOTC transshipment reports are compiled by the service provider at the end of each trip and submitted to the respective RFMO within a 2–3-week timeframe. All reporting formats and standards used by observers under these programs were originally developed by the consortium according to the specific requirements set out by each tRFMO. These forms were approved by their respective tRFMO and have since been standardized across all three tRFMOs. Summary observer reports are also sent on a five-day basis by ICCAT and IOTC observers on carriers, outlining vessels, dates, and locations where at sea transshipments occurred over that period. ICCAT also publishes observer reports on their website with relevant sections hidden for confidentiality purposes. Within the PNA program, the provider submits an annual report to the PNA office, not to WCPFC. Observer workbooks for reporting are provided by PIRFO and debriefing of observers is also done through a PIRFO qualified debriefer (generally from the national program). Debriefing reports are then sent directly by MRAG AP to the POA, who sends it to SPC, and finally from SPC to WCPFC. MRAG AP also works closely with the vessel companies and their agents in relevant ports to assist during observer placements with accommodation, meals, and transport for the observers, to ensure cost-effectiveness of the program.

WCPFC could implement an independent HS TS ROP that encapsulates a combination of systems currently employed by other tRFMOs and the PNA program. Everyday management and logistics of carrier observers can be handled by an independent party while a streamlined reporting system is developed by WCPFC. Carrier observer minimum data fields are currently being considered by the TSIWG and could complement the FFA transshipment observer standards and protocols work to establish transshipment observer and transshipment declaration forms. Together these groups can develop a transshipment observer reporting system that best fits WCPFC’s needs.

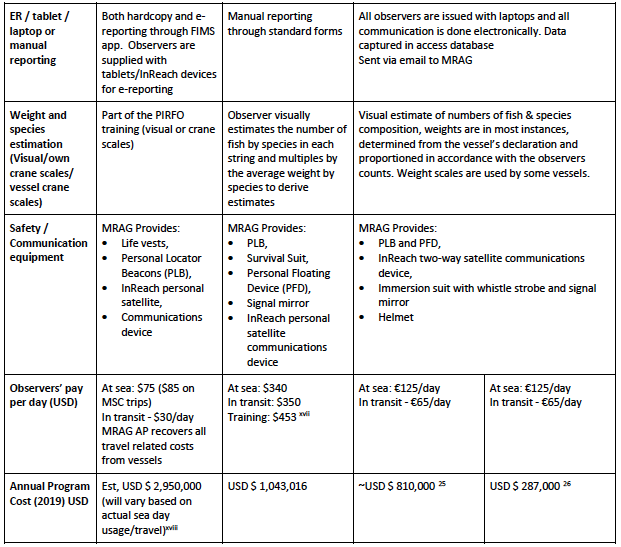

E. Program costs and cost recovery mechanisms

The costs of outsourcing these programs based on their respective 2019 operations (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic disruption), range from US$280k (ICCAT), US$810k (IOTC) to US$1.04M (IATTC) annually. These costs are recovered from the respective members of the 3 RFMOs that participated in at sea transshipments through their authorized longline vessels. For IATTC, the fee is calculated based on the total costs of the program and paid into a special account that the RFMO Secretariat manages. For the IOTC and ICCAT, costs are based on the quantity of fish transshipped in the preceding year. These costs are usually broken down per observers’ daily rates at sea and on shore (in transit or training).

The total program costs for administering the PNA observer program is based on the number of authorized fishing vessels and the number of fishing days per vessel. MRAG has fixed some costs that are charged to the vessels (to cover logistics) in addition to the $129 per day observer fee and other variable costs (flights, lodging and other logistical costs). The total annual cost for the 70 fishing vessels participating in the program in 2019 is USD $ 2,950,000. The POA has a 100% cost recovery mechanism from the flagged vessels similar to the other tRFMOs.

There is a clear overlap in the distant water fishing countries and entities involved in centralized HS TS ROPs at other tRFMOs (China, Chinese Taipei, Japan. Korea, Panama and Vanuatu) and those actively transshipping on the high seas within the WCPFC. It would therefore be reasonable to require that these countries pay for a similar system to monitor transshipments within the WCPO. There are multiple options that WCPFC can employ to determine program budgets and ensure full cost recovery. In addition, a centralized program should incorporate all costs associated with visa procurement for Pacific Island observers.

F. Secretariat requirements

At IOTC, ICCAT and IATTC, the Secretariat maintains the authorized list of carrier vessels, similar to the WCPFC Secretariat maintains its vessel registry. The three tRFMO Secretariats also receive transshipment declarations along with carrier observer reports. These reports are condensed by the providers and sent to the Secretariat to produce an annual summary of the program that is shared with all members. At IOTC, the Secretariat is also engaged throughout the observer deployment process and at ICCAT, the Secretariat receives near real time potential non-compliance reports submitted by the providers. Within the PNA OP, the provider submits reports to the PNA office, and it is inputted into a shared data systems that SPC can use to access. A similar process with transshipment reporting through SPC and the WCPFC Secretariat may be implemented for a WCPO HS TS ROP, keeping any WCPFC Secretariat tasks to a minimum. This Secretariat reporting system would also address a major loophole identified in WCPFC’s current transshipment program – the lack of transshipment observer reporting to the Secretariat. This approach leaves the Secretariat, the Commission, and its science provider – SPC without access to independent records of transshipment activity. A WCPO wide HS TS ROP could address this loophole by putting in place standardized transshipment observer reporting to the Secretariat without adding cumbersome administrative burdens to the WCPFC Secretariat.

Recommendations:

The current patchwork of transshipment monitoring processes in place at WCPFC lack minimum agreed data fields and verification processes present at the other tuna RFMOs. Building from the PNA OP independently run observerprogram, WCPFC could pilot a WCPO wide HS TS ROP. The main tasks of a pilot centralized WCPFC HS TS ROP provider would be to coordinate with the WCPFC Secretariat to:

Identify available observers from national programs.

Facilitate observer contracts and coordinating placement of observer’s onboard vessels

Coordinate flight, visa, and accommodation arrangements for observers.

Administer financial arrangements (including allowances for observers in transit)

Develop and administer a Code of Conduct for observers

Facilitate insurance for observers

Manage the provision of technical and safety equipment

Coordinate debriefing, data management and reporting

The proposed pilot could be completed by an independent party to provide a more detailed cost/benefit analysis specific to the region and detail efficiencies in operations which require:

Reporting minimum transshipment observer data fields and submission to the WCPFC Secretariat

Enhanced transshipment data sharing agreements with IATTC

Responses to transshipment observer reports from countries who transship