Longline transhipment

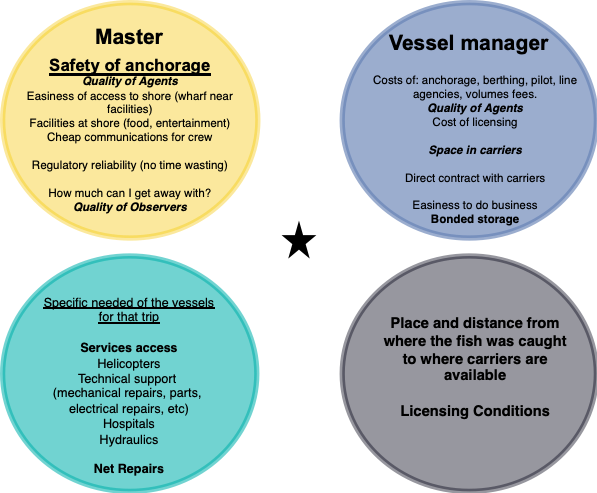

The factors affecting the profitability of a carrier trip were broadly the same across both longline and purse seine sectors, as well as between operators. The overwhelmingly dominant driver of profitability across both sectors was the time taken to fill up and unload. Time can be lost at the fishing end - e.g. if another trader beats you to the fish, or the fishing slows down – or the unloading end – e.g. if offloading is slow and the trader has to bear the cost of demurrage. To that end, carrier operators/charterers (e.g. tuna traders, logistics service providers) work in very close cooperation with prospective fishing vessels in the planning of trips and must make careful judgements about whether sending a carrier is economically justified.

In 2017, around 1,306 transhipments were reported in the WCPO purse seine sector, accounting for 952,151t of product (~ 79% of total purse seine catch). Although a total of 33 ports hosted transhipments in the period 2015-2017, activity was highly concentrated around a number of key ports, mainly in the central Pacific. Majuro was the key transhipment port, accounting for around 37% of all reported transhipments, while Pohnpei and Funafuti accounted for 16%, and 12% respectively. Our estimates indicate that somewhere in the order of 110-120 carriers (>1,000GT) were involved in purse seine transhipments in 2017/18.

The main considerations involved in coordinating carrier fleets servicing the purse seine sector are described, together with a ‘typical transhipment’. The key companies involved in purse seine transhipment in the WCPO in recent years are summarised including the main tuna traders, integrated harvester/carrier companies and standalone carrier operators.

In the longline sector, the key fleets involved in transhipment in the WCPO are the distant water bigeye/yellowfin and albacore fleets operating on the high seas. As at March, 2019, there were 2581 longline vessels on the RFV. Of these, 2,050 (79%) were authorised by their flag State to tranship on the high seas under CMM 09-06. Of the 18 States which flag longline vessels in the WCPO, only six authorise their vessels to tranship on the high seas: China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, USA and Vanuatu. Collectively, the Taiwanese, Chinese and Japanese fleets account for 83% of all high seas authorised longliners.

In 2017, the Taiwanese longline fleet accounted for around half of all high seas transhipments. China accounted for the next highest number (25%), with the Japanese fleet accounting for less than 2% of all reported events. The nature and operation of the main longline fleets involved in high seas transhipment in the WCPO are described.

The number of reported high seas longline transhipment events has increased by around 60% between 2011 and 2017 (at least some of which may be the result of better reporting). Much of the increase has come from the Taiwanese fleet (an almost four-fold increase in reported transhipment events between 2013 and 2017), with increases also evident in the Chinese, Vanuatu and Korean fleets.

In 2017, around 22% of the total estimated WCPFC-CA longline catch of the three key target species (BET/YFT/ALB) were transhipped on the high seas according to transhipment declarations received by the WCPFC. Bigeye recorded the highest proportion, at 42.2% of total catch, with albacore and yellowfin 18.9%, with at 11.6% respectively. The majority of reported high seas transhipments occur in tropical areas (20oN – 20oS) between 170oW and 120oW.

The number of carrier vessels receiving longline transhipments remained relatively stable between 18 and 27 during the 2011 – 2017 period, although the composition of flag States changed considerably.

Longline companies indicated there are substantial efficiencies associated with transhipment at sea, in particular reduced fuel costs and avoiding loss of fishing time associated with streaming to port. This was particularly the case for small vessels who have limited fish and fuel holding capacity and would spend proportionally more time steaming. Other benefits included cheaper bunkering and provisions, no licensing and port fees and less administrative paperwork and agent’s fees. Several large vessel owners advised that transhipment at sea was central to the operation being viable. Many longline companies told us they actively avoided transhipping in Pacific Island ports because of the higher level of compliance scrutiny involved.

The key companies involved in high seas longline transhipments in the WCPO are described, together with the dynamics of carrier fleet organisation.

POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE

Broadly, the membership of the WCPFC can be split into three groups based on the extent to which they participate in, and ultimately support, high seas transhipment:

‘supporters’ of high seas transhipment - these countries, most notably DWFNs Taiwan, China and Korea, have fleets who rely heavily on high seas transhipment as part of their operational and economic model. Broadly these countries are strongly supportive of maintaining ‘properly regulated’ high seas transhipment;

‘opponents’ of high seas transhipment - these countries, most notably the FFA/PNA member countries, have no involvement in high seas transhipment (other than Vanuatu flagged vessels) and strongly support transhipment reform. Broadly, the basis for their position is three-fold: (i) they are concerned that weakly regulated and monitored high seas transhipment represents a significant weakness in the MCS arrangements for shared stocks in the region, (ii) they see transhipment at sea rather than in adjacent PIC ports as a lost opportunity to deliver economic benefits to PIC communities; and (iii) related to (i), they see high seas transhipment as a missed opportunity to undertake comprehensive (and cost effective) compliance checks on vessels in port; and

The ‘others’ – these countries have a range of nuanced positions which don’t fit neatly into either group above.

Our discussions indicated that the response to any ban on high seas transhipments in the WCPO would be complex and difficult to predict with any certainty.

Taiwanese and Korean fishing companies indicated their vessels would return to east Asian ports (either their homeport, or Japanese/Korean market ports) rather than unload in PIC ports on the basis that (i) east Asian ports offer a range of services (e.g. cheap provisions/bunkering, technicians, etc) unable to be provided by PIC ports, (ii) freight costs would be saved by delivering fish direct and (iii) vessels would avoid the higher costs and stronger compliance regimes operating in PIC ports. Companies

were of the view that while ‘many’ operators would go out of business, smaller boats would be hardest hit given limited economies of scale and a higher proportion of steaming to fishing time. One operational response may be a contraction in fishing effort away from the more distant fishing grounds in the central and eastern Pacific towards more westerly grounds, closer to east Asian ports.

Some fishing base operators in PICs thought that a ban on high seas transhipment may mean many current high seas vessels would begin to make partnerships with companies like them who knew the ‘local scene’. One consequence then may be increased requests to reflag vessels to PICs, or alternatively register charters.

For vessels able to survive the shorter-term economic impacts, many longline companies thought there would be a longer-term market and operational correction– fewer fish being caught means higher catch rates over the longer term, as well as higher prices for fish, so those able to stay in the game may receive some longer term benefits. To that end, the impacts of a ban would be dependent on each individual operation’s capacity to adapt to the new environment. Longline companies also indicated that if PICs had better container services they would consider unloading in port, but to make in port landing attractive they would also need better support services – food, bait, fuel, etc.

At the carrier company end, all operators thought that a high seas transhipment ban would increase costs. In addition to a requirement to pay PIC license fees, carrier operators made the point that in the longline sector carrier companies are dealing with much smaller volumes than purse seine, making it operationally harder to coordinate a full load (even harder if the number of longline vessels reduces).

If a high seas transhipment ban saw a proportion of the longline fleet go out of business with many of those remaining choosing to offload direct to east Asian ports, there would likely be a contraction in the carrier market. The impacts are likely to be hardest felt by those operators who own, rather than lease, carriers given the capital involved. A contraction in demand may precipitate the scrapping of some carriers nearing the end of their productive life.

CURRENT MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING

The main instrument regulating transhipment (at least on the high seas) in the WCPFC-CA is the Conservation and Management Measure on the Regulation of Transhipment (CMM 09-06). Despite isolated successes, any clear-eyed assessment is likely to conclude the CMM has not achieved its objectives. Contrary to the intention to allow at sea transhipment only in limited circumstances, the number of vessels authorised to tranship on the high seas is almost double those that aren’t (2,355 Vs 1,229 as at April, 2019), the number of reported high seas transhipments in 2017 was more than twice that in 2012 (with the number of offloading vessels increasing by 90% over the same period, albeit at least some of this may be an artefact of better reporting), and the quality of information available to the Commission to independently verify reported catches remains very limited.

There is no doubt a range of reasons why implementation has not matched expectations, but three arguably stand out:

Weak implementation of the observer program - although intended by CMM 09-06 to be a primary tool to verify compliance, the high seas observer program appears to be largely ineffective at the moment. There is limited use of standardised forms or manuals and only a fraction of data collected by observers has made its way to the WCPFC to date. Crucially, the absence of observer information on catch volumes and species composition limits capacity to independently verify information submitted in transhipment declarations.

No agreement around guidelines for ‘impracticability’ - A key component of the CMM is a prohibition on vessels from transhipping on the high seas unless “it is impracticable for certain vessels … to operate without being able to tranship on the high seas…” Despite a number of attempts, no guidelines have yet been agreed around ‘impracticability’. In the absence of such guidelines, the CMM requires CCMs to apply interim guidelines, namely that a ban on at sea transhipment would cause significant economic hardship and the vessel would have to make ‘significant and substantial changes to its historical mode of operation…’. The fact that CCMs have paid limited attention to these interim guidelines is evidenced by the fact that more than 470 vessels on the RFV currently authorised to tranship on the high seas were built in 2010 or later – and therefore could not have had to make changes to their ‘historical mode of operation’. Moreover, the fact that five of the six CCMs who authorise their longliners to tranship on the high seas authorise >98% of vessels indicates that authorisation is being applied as the ‘default’ position, rather than after some ‘meaningful’ analysis of impracticability.

No serious attempt to encourage vessels to tranship in port - In the spirit of encouraging vessels to tranship in port, paragraph 35 (v) of the CMM requires CCMs of both offloading and receiving vessels involved in high seas transhipment to “submit to the Commission a plan detailing what steps it is taking to encourage transhipment to occur in port in the future”. To the best of our knowledge, no CCM has submitted a plan.

ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

There is little doubt that high seas transhipment faces challenges. Weakly monitored high seas transhipments have long been linked to laundering of illegal catches and broader IUU activities (e.g. Gianni and Simpson, 2004), while in more recent years serious concerns have been expressed around the capacity of at-sea transhipment to facilitate human trafficking, forced labour and other human rights abuses (e.g. ILO, 2013). These problems have led to increasing calls both globally (e.g. Ewell et al, 2017) and regionally (e.g. by the PNA) for ban on high seas transhipment.

For Pacific Island countries, their interest in high sea transhipment reform is strong and legitimate. Despite agreeing the WCPF Convention in 2004, which requires CCMs to encourage transhipment in port, and despite CMM 09-06 reinforcing the intent of the Convention, PICs have seen little practical progress from DWFNs to encourage transhipment in port. At the other end of the spectrum, DWFN fishing companies see high seas transhipment as a legitimate and globally widespread practice which generates efficiencies and forms an essential component of their operation. Subject to an effective management and monitoring regime, there should be nothing wrong, they argue, with businesses seeking the most efficient means to carry out their legitimate operations.

It is these polarised positions which set the scene for the upcoming review of the transhipment CMM. While on the surface there appears little common ground to be found, it is not inconceivable that both positions can be satisfied, at least to some extent. Getting to this future will require a range of reforms and investments, including:

CCMs should comply with the spirit of the WCPFC Convention to encourage transhipment in port.

Two main measures are required to demonstrate compliance with the intent of the Convention:

Those members who’s fleets currently tranship on the high seas should be required to submit tangible plans detailing the steps they will take to encourage their vessels to tranship in port.

WCPFC members should agree the circumstances under which it is impractical for a vessel to tranship in port.

Any vessel for which it is deemed impractical to tranship in port must be subject to a compliance regime that gives confidence that all transhipment activity is tightly controlled.

Key measures of an enhanced monitoring regime for high seas transhipments include:

3. Monitoring on all offloading vessels (e.g. longliners) (electronic monitoring or observers)

4. Examining the utility of EM on receiving vessels (e.g. carriers)

Measures to independently verify transhipment activity should be strengthened

A range of measures to strengthen capacity to independently verify transhipment reporting would be beneficial:

5. All CCMs which authorise vessels to tranship on the high seas should submit evidence of the processes andmechanisms they use to verify transhipment information submitted by their vessels.

6. Arrangements for the implementation of the transhipment observer program should be strengthened.

7. The Secretariat should consider additional measures to independently validate transhipment activity (e.g. inclusion of AIS data in transhipment analysis)

In addition to these core recommendations, observations are made around ensuring equivalent monitoring of fish transported via refrigerated containers and enhancing the attractiveness of PIC ports for longline unloading/transhipment. Observations are also made to improve the utility of carrier vessel information on the RFV.