Recently I was asked to think about what makes vessels to go to one port and not to another one for transshipment here in the pacific, as a continuation of what I wrote in the past about why we have so many transshipments here in Majuro, so I made a lot of questions to a lot of really kind people (thank you all!) plus my own experiences while onboard.

And here is the result, which I’m sure is imperfect, so I welcome all sorts of contributions… something I learned in fishing is to appreciate collective knowledge, as my first fishing master told me “no ones makes it alone”

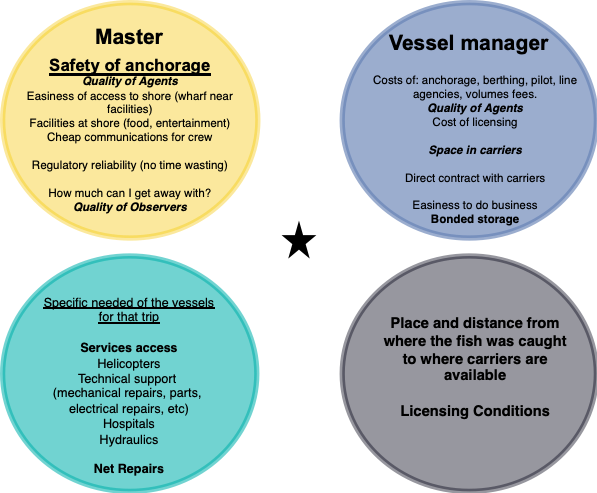

I identified four main decision-making drivers in deciding which port to aim for transshipment. The factors considered by each driver change and can have very different weight from trip to trip, hence the decision making is a fluid process. The drivers are:

Fishing grounds and Licensing

Denominated port in licensing conditions: some countries require that transhipments only occurs in their port as a licensing condition, this occurs normally for their own flagged vessels, or those fishing exclusively in their waters as part of chartering arrangements or JV. This, of course, overrides all other decision elements yet is a very crude tool and one that most operators do object.

Proximity to fishing grounds: Distance from fishing grounds to where carriers are available is an important factor, as the tuna trading companies attempt to place carriers in locations convenient to purse seiners based on current fishing conditions, as it is in both parties’ interest to complete transshipment as soon as possible after the purse seiner leaves the fishing grounds. Yet specific needs arising from the fishing trip, the sale of the catch, the logistics involved and the preferences of masters and vessel managers may dictate the use of another port, even if it is further from the ground.

Specific needs arising from the fishing trip

Services access: Purse Seiners and carriers are complex vessels, there is an incredible amount of machinery and technology that needs parts and maintenance: from propulsion to electricity generators, to hydraulics, to refrigerate 900 tons of fish, to maintain the electronics, etc. While most repairs are done on board if land-based services are needed the preference would always be to those ports having access to well-stocked and capable staff ready to support a rapid turn around.

Helicopter base: While the role of helicopters onboard is coming to an interesting situation, as they compete now with drones and by the fact that most fish are caught on FADs with sonar buoys… they still an important element of the industry. The helicopters don't belong to the boat but are subcontracted by the boat owners from specialised companies, that provide the helicopter itself, the mechanic and the pilot to go onboard. Helicopters need a lot of maintenance, their own fuel, and their own “set up”. Yet the flight to repair base inside a country does require not only proximity to the vessel but also aerospace permissions. The combination of land facilities near the vessel and easiness in the facilitation of their operation while in port is an important driver in the decision making.

Health facilities on shore: While the evacuation of a critically injured crew member is governed by maritime and crew welfare rules, in non “life or death” situations most masters will have no qualms in steaming 24 or 48hs more to get the crew to the port offering the better facilities.

Flights frequency and connections: a need for international frequent and varied air travel connections for key personnel (including vessel manager)

Master of the vessel

Safety of anchorage: the safety of the vessels is the ultimate responsibility of the master of both PS and Carriers. As transhipment occurs on the anchorage of the carrier a good solid ground for anchoring is key to the carrier that often has two Purse Seiners transhipping (one on port and one on starboard) and all depending on the carriers anchor, hence no dragging is paramount. Furthermore, dragging is a consequence of wind and swell exposure, therefore the more protected the anchorage area the better. Therefore, enclosed lagoons would always be preferred over open ones.

Quality of the agents: Agent plays a key role in the transhipment tuna world, and is a role not very well studied. They lease in-between vessel owners, captains, traders, carriers, and the line agencies and is their responsibility to have all sorted and can arrange for solutions of most problems arising while providing translation (since the bulk of the fleet speaks some Asian languages. Hence having a variety and quality of Agent’s staff that are available 24/7 is a very important driver

Regulatory reliability: Having all line agencies (immigration, biosecurity, customs, etc) lined up on vessel arrival (no time wasting) is an important element in the transhipment equation. This has to be a 7-day operation.

Easiness of access to shore: having easy access to a wharf near the main facilities in town for crew influences a master’s choice. These facilities compromise not only food and entertainment but access to local SIM cards with affordable data plans for the crew to communicate with family

The reputation of the Fisheries Observers: with some exemptions vessels get onboard observers that are nationals of the port state where they are transhipping. Repeated bad experiences by the masters with observers (drunkenness, violence, corruption, etc) and/or repeated good experiences with observers from a certain nationality are known to fundamentally influence the master’s preference for certain ports. I have to admit that this one came as a bit of a surprise, but in hindsight makes total sense and totally explains why one of our less serviced ports (yet has some of the best and healthiest observers) get a lot of vessels,

Weak regulatory oversight: weak regulatory oversight in terms of Port State Measures best practices and IUU fishing by national fisheries administrations, can act as a perverse incentive for some skippers. This of course, is not something that states should pursue as an option.

Vessel manager

Costs: Cost is an important factor for vessels managers, the sum of anchorage, berthing, pilot, line agencies, transhipped volumes fees, as a supplementary influence on port choice; yet more expensive ports sometimes leverage this with better services, observers, etc. The cost of agents is also important here and relates to their quality as already discussed

Carriers require a license to operate in the port state (normally on annual basis) and if they have to operate in various states this can add to having them based in one port only.

Relationship with carriers: various options based on existing contractual arrangements with the carrier but also cargo space trading in between operators make the decision making vary from Purse Seiner trip to trip. As operators may offer space to a “rival” if that allows the carrier to be full and head towards the processing country, particularly when there is low stock in the canneries

Easiness to do business: having a conductive, secure and low bureaucracy business environment is a big advantage for any country into attracting any form of use of ports, transhipments are no difference

Skilled Stevedores: Daniel Calvo Butron told me this is afctor on pther parts of the world, here in the pacific where asian fleets dominate, crew takes care of sorting and loading the nets sling for the transhipemnt so nt an issue for us.

The figures above illustrate the interaction between these areas and how they combine into the election of a transshipment port, which potentially can vary from trip to trip.

Very importantly you don’t need a big wharf for transhipments, just a good lagoon, yet having a wharf that facilitates the provision of services, unloading of fish and gear as well as facilitate inspection, for example, amplifies the benefits of some of the points discussed, but also the needs associated to it.

A big talk is always about the need for a big “net repair yard” on transshipment ports, yet that is only part of the picture, and we need to understand why ad if you need it

Fundamentals of Purse Seine nets design and their repair

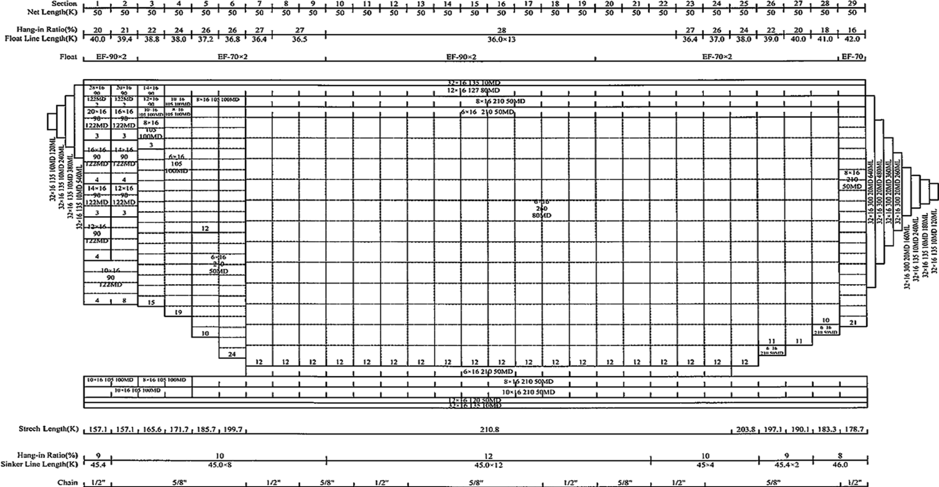

Purse Seine nets design, architecture, and construction have had a substantial evolution in the last decades associated with progress on computational modeling. The net plan of a contemporary net of 3000 m long, 300 m depth and weigh and estimate 6 tons (net only), is presented below for illustration purposes.

Schematic diagram of the commercial tuna purse seine of braided knotted nylon netting with different large-mesh panels, mesh size is 300 mm, 450mm at the bottom, the number of vertical netting panel is 20, and the number of horizontal netting panel is 640. Source: Hao Tang et all, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2018.11.018

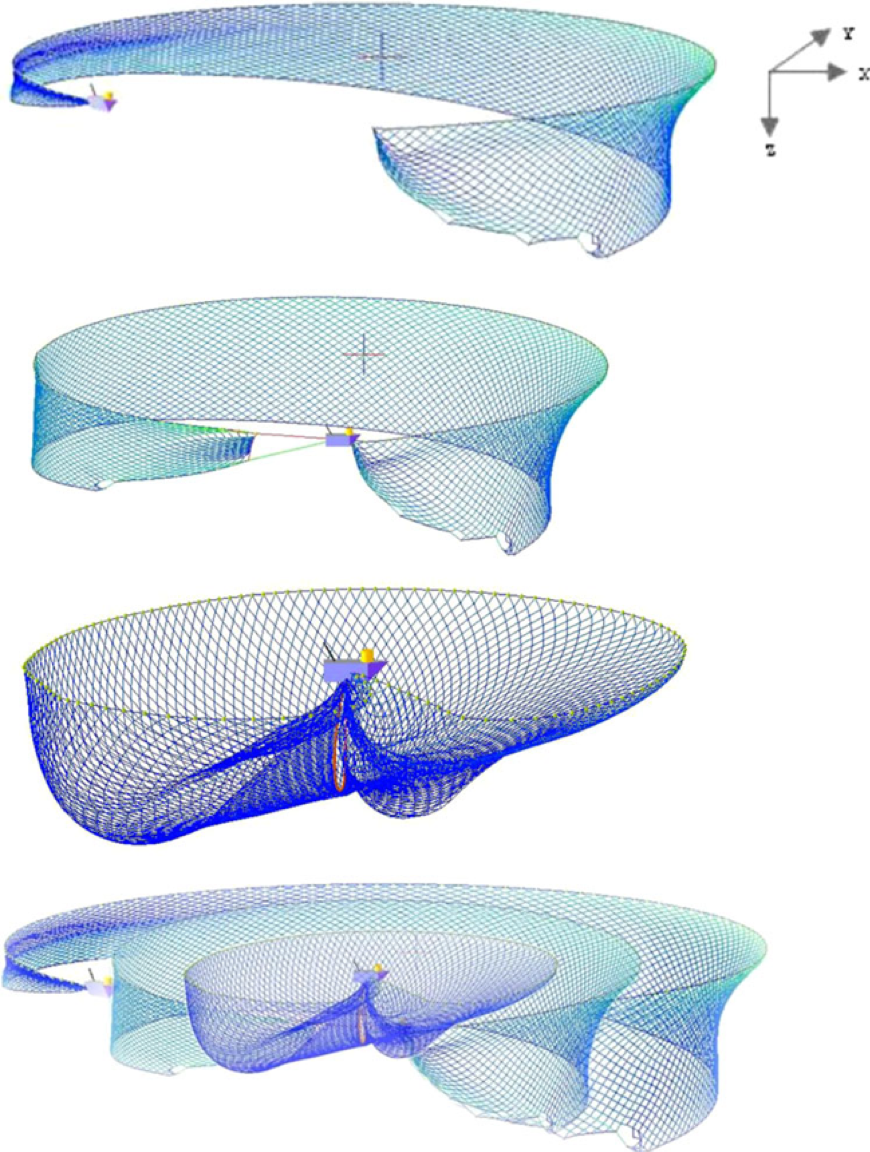

These complex designs arise from the understanding of the “adaptive” geometry needs associated with their deployment and hauling, and their “behavior” at depths of up to 300 m under potentially differential currents strength and direction. A schematic diagram of these shape sequence is presented below for illustrative purposes.

The sequential shape of the simulated purse seine gear from shooting to the end of pursing under a pursing speed of 1.3 m/s and current speed velocities of 0.11, 0.40, and 0.38 m/s for the three layers. Note that the seiner pulled into the center of the enclosed net area. Source: Hosseini et all, 2011. DOI 10.1007/s12562-011-0371-6

These advances have made the fabrication (and therefore the repairs) of Purse Sine nets becoming highly complex in terms of capacity, supplies and infrastructure needs.

Like any other onboard gear, nets require maintenance, different level of repairs and replacement. The reasons for repairs vary yet common causes are wear and tear, bad weather, accidents bad maneuvering, the release of accidental capture, gear failures, etc.

Most usual repairs are done onboard while at sea, as shown in the picture below:

Medium to major mends require big flat surfaces such as a wharf to extend parts of the net and allow for panels to be fix or replaced, in many cases it would also require a forklift to move the net around, in important to note that in this cases the net remains “integral” and only the parts to be repairs are “landed” while still “attached” to the vessel, hence the wharf and wharf face becomes unusable for other operations. Having a wharf were to extend the part of the net to be repaired, without having to unload the whole net, is a fair compromise solution in many ports that do not have the capacity to expand into a workable net yard (see next section) and/or cannot recruit a net master. The picture below shows one example of part of the net being repaired on a wharf.

Critical repairs need a net yard with lifting gear, cut netting panels, twine, rings, floaters, etc. As it will involving the total unloading of the net and the removal of the net from wharf face as to liberate it for other operations and let the vessel go.

There are no standardised requirement of size for a net yard, but it can be described crudely as a football field next to wharf, the smallest operational yard in the region is 180x60m approximately of hard surface and incorporates the following facilities: Net handling equipment (hydraulic booms and power-blocks, heavy-duty forklifts, crane truck, etc), Winch house, Lighting, Materials store, Security fence & access restrictions. The picture below shows a panoramic view of a small net yard in the region, from the vessel perspective and then from the winch house one.

Yet equally important (and not always considered) is that they require the availability of a good Net Master ( a rare and exotic bread these days), able to understand the net plans and identify the parts of the net to be replaced, and in many cases adapt existing mesh to fit the needed parts.

Finally, there are no guarantees on how many days a year a net yard works, as this will depend (among others) of: how many vessels are required to come, the capabilities of the net master, how much more competitive you are in comparison to Majuro and/or the nets going back to factory onboard carriers.