Containerisation in our region is around 2-3% of the total catch due to a set of infrastructure limitations we have, and the fact that traditional transhipments via carriers would not disappear any time soon as I explained before… particularly because most people don’t consider that the job of carriers bringing stuff is as important as the one of taking fish back to processing ports. Carriers have also a fundamental role in providing goods and parts to fishing vessels (i.e. food, mechanical parts, oil, salt, foaming and cleaning agents, ropes, cabling, net components, fishing gear, etc.).

Containerisation requires a good level of port facilities, infrastructure, and reliable electricity supply yet equally important operations and logistics management. Yet it also needs the fishing vessels to come to port, which is costly as it requires port use fees, agents, etc.

Purse seiners (PS) fishing in the WCPO are obliged to only tranship in port as licensing condition since 90% of the skipjack occur in the EEZ of the FFA members that are part of the Parties of the Nauru Agreement (PNA). Therefore, the alternative of containerisation is potentially more accessible.

The situation for the Pole & Line (P&L) fleet is similar since they only operate from one port in the region.

Yet the situation is totally different for the longline fleet, since most of the fishing effort (~60-70%) occurs in the high seas (HS). In the southern longline fishery, about 30 to 40% of the effort has been in the high seas in recent years. This means that coastal countries have much less leverage in the longline fishery as to oblige vessels to come to port, and an increasingly substantial volume of the fishery is transhipped in the HS.

Countries licensing longlines to fish in their EEZ, worry that by implementing unloading in port obligations, the vessels just would move to the HS, and this will impact licensing revenue.

While under WCPFC CMM 2009-06 at sea transhipments are not allowed in the WCPFC, yet there is an “impracticability exception” which has been abused. This is because impracticability is not defined nor explained, so many boat owners take advantage.

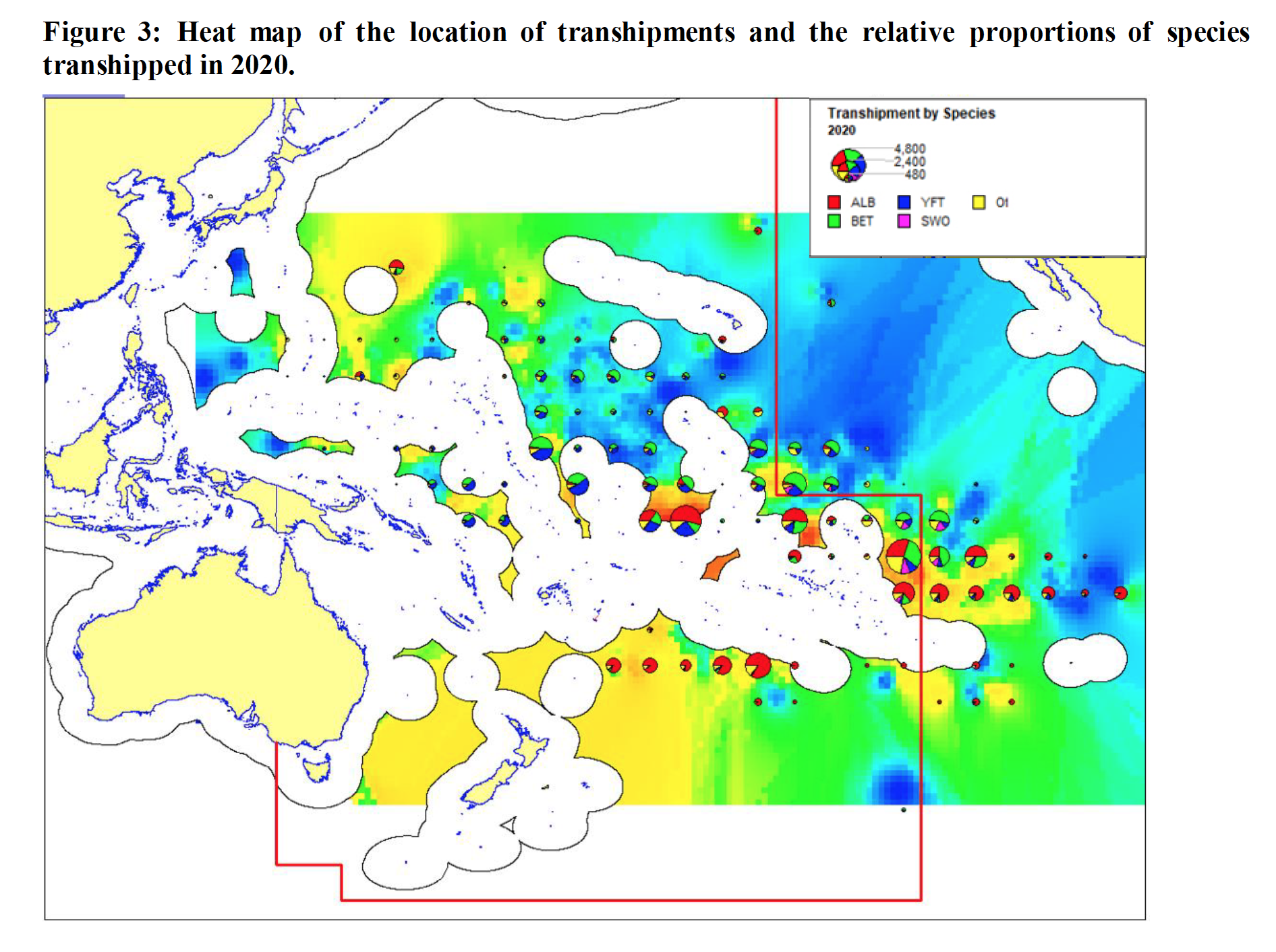

Consequently, in recent years, the number of reported at-sea transhipments within the WCPFC Convention Area increased by 166%; from 554 transfers in 2014 to 1472 in 2019 (WCPFC 2020a[1]). Furthermore, as of 13 November 2020, 62% of vessels on the Record of Fishing Vessels (WCPFC 2020b[2]) were authorised to tranship in the high seas (WCPFC 2020b). The same study shows that the fishing vessels allowed to tranship at sea are mainly flagged to Taiwan, China, Vanuatu and Republic of Korea, and that the carriers receiving that fish are flagged to Taiwan, Panama, Korea, Liberia, China and Vanuatu.

For the longline (LL) fleet coming to port implies higher expenses than transhipments at sea, hence containerisation of landings is mostly limited to vessels associated to coastal states by permits, vessels chartered to local companies or domestic vessels.

Freezer longliners can also be sub-divided between those that have ultra-low temperature freezing (ULT) capability at -60°CC and those that have -35 to -40°C freezing capacity, with the former commanding a price premium, hence the option of unloading fish aimed at ULT sashimi market is and tractive for vessel owners, albeit the expenses. In fact, many vessels licensed to coastal states land and containerise their ULT tunas and tranship the rest of the catch of lower value (i.e. swordfish, marlins, mola mola, mahi mahi, wahoo, and permitted sharks)

As the realities of the fleets are so different, I analyze each fleet independently, albeit some of the ports used being the same.

Purse Seine

As discussed, the WCPO PS fishery relies mostly on transhipments. Containerisation takes place on a much lower scale and is generally associated to specific ports and logistics arrangements. In some cases, vessels do tranship skipjack and smaller yellowfin and bigeye, but also unload for containerisation the bigger YF and Big Eye to be added to the longline value chain.

In PS fisheries containerisation traditionally occurred without grading into species or direct weighing of fish, which are only estimated – through good approximations are generally obtained when containers reached capacity. Yet, theoretically offers the opportunity to sort catches by species and/or size, thus enhancing the opportunity for diversified marketing.

On board logistics

Once on board, tuna pass below deck to be loaded into wells. Bigger vessels employ chute systems while other conveyor belt systems to direct catch into desired wells, that also quickly deliver catch to wells. Tuna in PS are generally chilled whole in refrigerated seawater (RSW) without bleeding, or removing the gills, or gutting, and then brine immersion freezing. This technique involves storing fish in brine (made by adding salt to sea water) and reducing the temperature of the brine until the fish (but not the brine) are frozen.

Freezing such large amount of fish requires very large powerful freezing equipment and high volume wells which occupy much of the lower part of the vessel and are equipped with batteries of pumps for brine and RSW circulation. In the larger vessels, there are also ”dry or side lockers” that work a "additional freezer" where already brine frozen fish is stored “dry” (as without brine). Newer vessels also have specially adapted “dry locker" that act as blast freezers for higher value species, like those in LLs that can freeze and maintain to -35C

Landing logistics

Once a PS comes to wharf side and is tied up it can take a while until unloading is authorised depending on the level of inspection and regulatory steps required.

Once landing is authorised, the following steps take place:

From well to deck

The “lifting” of the tuna out of the wells can be done in two distinctive ways:

Dry fish

In traditional unloading, the brine is pumped out of a well and the hand expansion valves are turned off an hour or so before the start of unloading. If a well is not packed too tightly, and the salinity of the brine used for brining and re-brining and the temperature in the wells are properly adjusted, the unloaders should be able to “hook” the fish loose from the mass of frozen fish and loaded into the cargo nets to the deck.

Increasingly tuna is classified by species before loading into the net, and then sent up in separate nets, and/or further are separated on deck and put in different nets prior to unloading.

In newer vessels, frozen fish from the wells is removed during the finishing trip and stored in the dry/side lockers that are never brined. Tuna is stored separated by species; the unloading process works on the same principle as the nets.

This is by far the most common way of unloading for transhipment and landing.

Wet fish

Often fish are unloaded by the “floating off" method when they are to be transhipped. Under this procedure, the brine is left in the well during unloading. As soon as individual fish separate from the mass of fish they float to the top of the well since the brine has a greater specific gravity than the fish.

Long-handled hooks are used to separate the fish. The floating fish are taken out of the wells and moved via conveyor belts or chutes straight to shore and put in cargo nets, which are hoisted from the hold to the deck.

Wet fish method is often used when the unload goes straight into bins for processing or storage, but is not used for transhipping or containerisation since the ability to handle fish loaded in the holds of carriers or stuff them into a container as 'wet fish” is lower, as fish to then be removed from containers is frozen together taking more to operate, and resulting in higher rejects from broken fish.

From deck to wharf/pier

Once fish is on cargo nets on the deck of the Purse Seiner, they are hoisted by one of the cranes of the vessels or by shore-based one, straight to the wharf or to a platform at the wharf, either using one of the vessels' own winches or a shore-based crane.

A recent innovation that has accelerated the efficiency of unloading times, is the use of loading platforms to sort and load fish.

Loading (stuffing) of Containers

This is a mostly manual operation albeit with the different levels of mechanisation available in terms of loaders. They involve stevedoring staff in the wharf, platforms, and inside the containers, requiring regular breaks and staff rotation.

Stuffing a container manually with 20 tonnes of fish can take around 2 to 4 hours, depending on:

The weather (unloading is always suspended when it rains as it “wets’ the fish and also the whole operation becomes more slippery and therefor unsafe for operators)

Quantity and experience of stevedoring staff

The use of different types of chutes or conveyors to move fish into the container.

This compares with the ability of more sophisticated loaders able to stuff a full container in one hour.

The working hours correspond to those of the unloading vessel, usually, 7 am to 10 pm with various breaks for food. Yet in some cases, if the unloading is done with a contracted unloading crew, the process can be done over 24 hrs, yet this is very unusual. Photo 3 show the “stuffing” of PS tuna

Controls by fisheries authority normally take place during this stage (either officers or unloading monitors depending on the port state set up) evaluate volumes, estimated species composition, species of interest, etc.

Representatives of both, the unloading vessels and the responsible for the containers, are also part of these controls since accurate weights per species are key for crew payments and insurance premiums for the shipping of the containers.

Efficient shore storage logistics are fundamental, since unloading from the vessel is a time-constrained operation and requires enough precooled containers and at least a loaded container lifting/moving machine and depending on the distance to the plugging points, container moving trucks, etc.

Once containers are fully loaded, they are moved to the electricity connection points “plug in” points able to provide 360-500 Volt, 50 or 60 Hz for the refrigeration units to freeze down the tuna to at least-18C.

The cooling down can take many hours depending on the general temperature of the loaded fish and the "stuffing density’, as cooled air sped, and circulation are dependent on it. Containers need to reach the set temperature range specified by the shipping company before the container ship will allow them to be loaded.

Shore storage and container loading logistics

Reliability of industrial power supply (360-500 Volt) is fundamental for storage, and this has been historically a problem in the region. ADB (2019)[4] reports that the Pacific region faces a unique set of electricity challenges. Its limited supply of domestic fossil fuel resources has led to a historical dependence on imported fuels for power generation, and a corresponding vulnerability to fluctuating energy prices. At the same time, outdated power infrastructure, geographical dispersion, small economies of scale, and limited generation capacity lead to high electricity tariffs (or costly subsidies), transmission and distribution losses.

Summed to this reality Van Duin et all (2019)[5] reports that refrigerated containers are responsible for 40% of the total energy consumption of container terminals, when connected to the electricity grid on shore. Every time when many containers are plugged in after arrival, peaks in energy consumption occur.

While power consumption is high after plugging in, once the cargo has been cooled to low-temperature mode (below -10°C) the refrigeration unit is run in on/off mode, hence the average power consumption falls. Yet, power consumption per container is affected by environmental variables such as ambient temperature, wind speed and the level of direct sun exposure of the container.

CHB[6] (2021) reports that a 40' refrigerated container set at -21C and operating at a ambient temperature of 37.8°C, has average power consumption values of approximately 5.3 to 4.5 kW according to the type of refrigeration unit used.

Container ships operating to most pacific ports are self-loading (they have their own container loading cranes on board) and operate on tight schedules allowing 12-24 hrs operations per port. Therefore, the port container logistics need to be tight and involve the agents and all line agencies (Port Authority, Customs, pilots, biosecurity, immigration, etc).

Containers need to be arriving in sufficient numbers to be loaded in an uninterrupted way while minimising temperature loss. The cargo vessel Chief Officer will check the minimum temperature once containers are plugged in onboard, and containers out of the temperature range are rejected.

Shipping agents and exporters need to have all documentation ready and approved, i.e. Load list for all containers and verified weights per container, shipping instructions (with individual container identification), Bill of lading, export permits, and depending the jurisdiction and destiny, specific clearance for illicit drugs, biosecurity, bioterrorism and other may be required.

Longline

In the WCPO, there are two longline fisheries – the Southern and Tropical longline fisheries. Vessels operating within the Tropical longline fishery are typically large-scale distant water vessels fishing between 20ºN-20ºS, which target bigeye and yellowfin for sashimi markets, with smaller volumes of incidentally caught albacore. Vessels operating in the Southern longline fishery are typically smaller (<100GT) and target albacore for canning markets in subtropical waters below 10ºS and have small volumes of incidental bigeye and yellowfin bycatch.

With advancements in freezer technology, particularly for the smaller vessels, the distinction between the tropical and southern longline fleets has become less obvious, with some vessels now having the ability to switch targets depending on seasonality, fishing location, stock abundance, etc., moving between both fisheries.

There is an important intersection between some freezer longliners (large and small-scale) and both the sashimi and canning-grade chains. A longline vessel's albacore may be sold for canning, while BE and YF is sold for sashimi/value-added products. Importantly, and more recent development, high-quality albacore is increasingly consumed as sashimi in Japan. Japan traders mostly only take albacore from Japanese vessels and sometimes Taiwanese ones.

The albacore needs to be handled properly onboard (and differently to canning grade albacore), so a conscious decision is made by vessels to catch and handle albacore for the sashimi market.

FFA 2017 estimated that collectively, China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan's longline vessels have accounted for 75-83% of the total number of longliners active in the WCPO. In terms of catch volume, these fleets have accounted for 39-48% of total longline catch under flag-based allocation, with additional catches attributed to chartering states.

Japan is the major global market for sashimi quality tuna, accounting for around 80% of global sashimi consumption originating from tropical tuna catches, FFA 29017 estimates that 65% is delivered by reefer carrier, 15% by ULT containers, and 15% by longliner vessels offloading directly (e.g. the Korean fleet).

For longline albacore, an estimated 50-60% of the catch is consumed on the US market (FFA, 2017) the rest is processed mostly in Bangkok.

On board logistics

Once on board, catches are, depending on the species, processed to a different extent on board; yellowfin, bigeye, and bluefin are bleed, chilled, gilled and gutted (eviscerated), fast-frozen, and then stored at -35C or -60C depending on the vessel characteristics. Lower value species are normally gutted and either gilled or head and fins removed to then sent to freezer storage.

Most Asian longliners in the WCPO have a very similar deck configuration, one hatch with a door entry on the stern side of the deck, one “central” hatch, and two equally sized hatches towards the bow end of the deck.

For the last decade, most fish caught in freezer longliners get a closed loop of monofilament line added to their carcass (normally to the caudal end and called “tail loop" during processing, to help with their transfer, movements on board, and unloading.

Landing logistics

Once a LL comes to the wharf side and is tied up it can take a while until unloading is authorised depending on the level of inspection and regulatory steps required.

Once landing is authorised, the following steps take place:

From hatches to deck

Crew wearing freezer gear enter the hatches and remove fish one by one.

For those fish in hatches at main deck level, the fish is dragged out. For fish below deck, a closed circle of thicker rope is fed through the “tail loop" to gather the fish together. The ends of this thick looped rope were slipped over the hook at the end of the vessel's winch/boom cable. Initially, the fish are removed from the LL vessel's hatch, with its cable and hook, and then placed on the deck.

From deck to wharf/pier

From deck to wharf depending on the height difference in between the vessel's deck and wharf side as well as tide range.

In the case of the vessel being at level or above the wharf height, chutes or sometimes conveyor belts from the wharf are used to disembark the fish.

When the wharf is above the vessel height, either the fish is placed on cargo nets on the deck of the longliners, or a closed circle of thicker rope is fed through the “tail loop" to gather the fish together.

Then either the ends of this thick looped rope or the four corners of the cargo net are slipped over the hook at the end of a shore-based crane cable to be hoisted to thick canvas or to a platform made out of plastic pallets at the wharf.

In the best-case scenarios, the refrigerated containers are placed as close as possible to unloaded fish, but in others the fish may be loaded in trays or cages and then transported by forklift to the “mouth” of the containers.

The working hours correspond to those of the unloading vessel, usually, 7 am to 10 pm with various breaks for food. Yet in some cases, if the unloading is done with a contracted unloading crew, the process can be done over 24 hrs, yet this is very unusual.

Containers can either be directly opened or through a covered “tunnel’ normally a container with both ends open. This tunnel protects from potential rain or direct sun.

In both cases, there is an electronic scale there where fish are weighted one by one, or in groups of the same species prior to being loaded into the precooled container.

Controls by fisheries authority normally take place during this stage (either officers or unloading monitors depending on the port state set up) evaluate volumes, estimated species composition, species of interest, etc.

Representatives of both; the unloading vessels and the responsible for the containers are also part of these controls since accurate weights per species are key for crew payments and insurance premiums for the shipping of the containers.

Loading (stuffing) of Containers

Fish is accounted "tallied " and then manually stuffed into the containers, until weight capacity is reached, and the container closed.

Once containers are fully loaded, they are moved to the electrical connection points (360-500 Volt, 50 or 60 Hz) for the refrigeration units to freeze down the tuna to -35C. The cooling down can take many hours depending on the general temperature of the loaded fish and the" stuffing density" as cooled air sped, and circulation is dependent on it. Containers need to reach the set temperature range specified by the shipping company before the container ship will allow them to be loaded.

Shore storage and container loading logistics

The reliability of electricity is more important for ULT containers since the temperate requirements are higher and failures con be very costly.

Once containers are plugged in, the logistics and management are no different than those explained under PS

References

[1] WCPFC. 2020a. “Annual Report on WCPFC transhipment reporting. WCPFC-TCC16-2020-RP03, Technical and Compliance Committee. Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia.

[2] WCPFC. 2020b. WCPFC Record of Fishing Vessels. Accessed 13 November 2020, https://www.wcpfc. int/record-fishing-vessel-database

[4] ADB, 2019. Pacific Energy Update. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/545686/pacific-energy-update-2019.pdf

[5] Van Duin et al. 2019. Factors causing peak energy consumption of reefers at container terminals. J. shipp. trd. 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-019-0040-y

[6] CHB. 2021. Container Handbook. German Marine Insures organization. https://www.containerhandbuch.de/chb_e/index.html