I just quote below the executive summary, but this the type of publication people like me uses a lot as reference for years. Is compulsory reading, if you have any interest on the who does what in terms of DWFN Purse Seine in the region.

The purpose of this report is to provide industry and market intelligence to Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency members regarding the current status of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) distant water purse seine tuna fishing industry. This report largely focusses on six major distant water fishing nation (DWFN) purse seine fleets operating within the WCPO – Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China, US and the Philippines. Cross-cutting and fleet-specific industry dynamics are identified, and where possible, implications for PICs are drawn out.

WCPO Distant Water Purse Seine Fleet Overview

The Japanese pioneered tropical purse seine fishing in the WCPO, developing a commercial fleet in the mid-late 1970s. Several US purse seiners operating in the EPO commenced experimental voyages into the US-Pacific Trust Territory in the mid 1970s; by the early 1980s, the US purse seine fleet had shifted to the WCPO. Around the same time, the Philippines, Taiwan and Korea commenced purse seine fishing in the WCPO. China was the last Asian distant water fleet to enter the WCPO purse seine fishery in 2001.

From 1990-2006, the total number of purse seine vessels operating in the WCPO was relatively stable, ranging from 180-220 vessels. From 2007, vessel numbers increased gradually, when the vessel cap was replaced by a limit on fishing effort under PNA’s Purse Seine Vessel Day Scheme (VDS). In 2015, purse seine vessel numbers peaked at 308, but have since declined steadily to 271 vessels in 2018. The number of Pacific Island domestic vessels (i.e. Pacific Island-flagged, chartered and locally-based foreign vessels) has gradually increased since the mid-1980s, reaching 126 in 2018.

In the mid-1980s, when the WCPO purse seine fishery was first developing, annual catch was 400,000- 450,000 mt, accounting for around 40% of total WCPO tuna catch. In 2018, total purse seine catch was 1,910,725mt, accounting for 70% of total WCPO tuna catch. The WCPO fishery is essentially a skipjack fishery, accounting for 65-77% of purse seine catch; yellowfin accounts for 20-30% and bigeye only 2-5%.

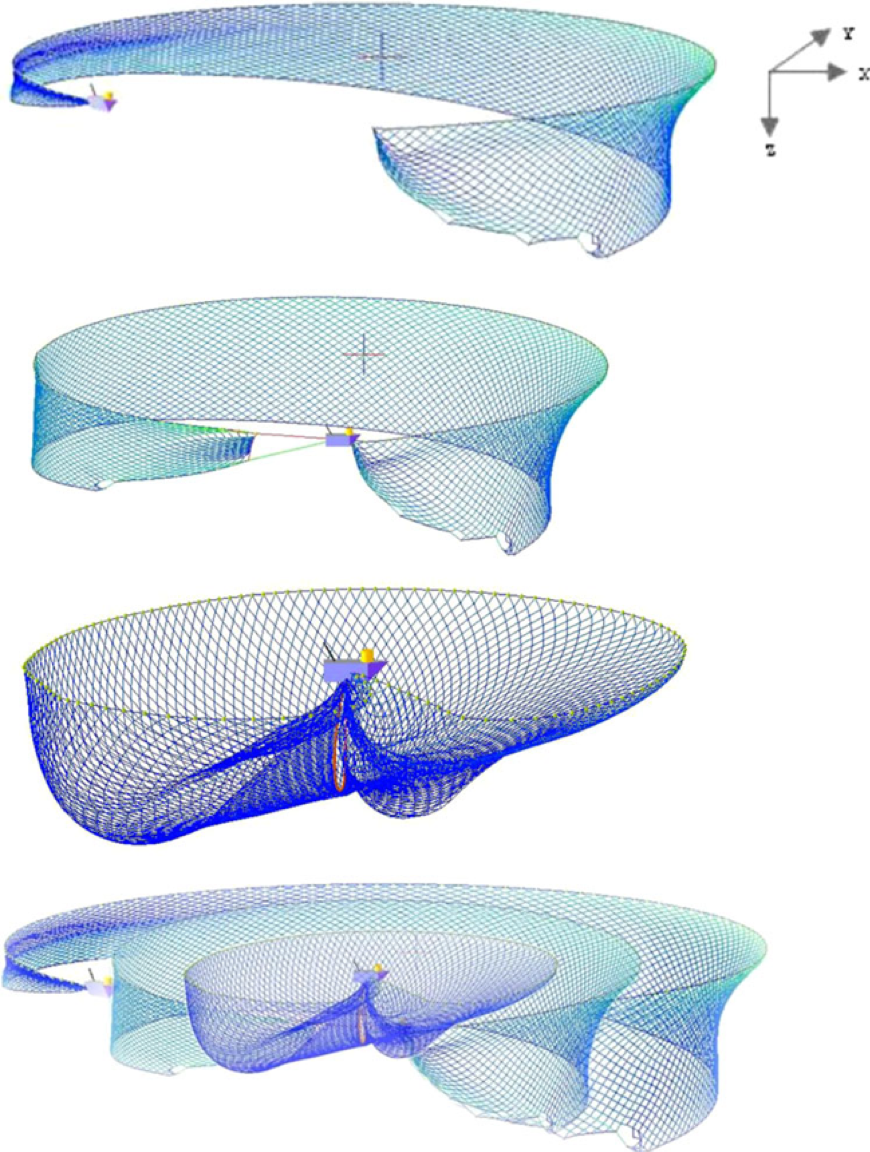

WCPO purse seine vessels target skipjack and yellowfin in free-swimming schools and around man-made drifting fish-aggregation devices (FADs) and floating logs. There are long-standing concerns about high levels of incidental by-catch of juvenile bigeye and yellowfin by purse seiners fishing on FADs. While stock assessment results indicate both WCPO bigeye and yellowfin stocks remain healthy, the recommended scientific advice is that management measures which reduce fishing mortality of fisheries that take juveniles should continue to be considered.

The majority of purse seine catch in the WCPO is supplied to canned tuna processors in Thailand. Raw material is also supplied to canned tuna and cooked loin processors in American Samoa, Central/ South America, Philippines, Korea, China, Vietnam and Japan. Around 100,000 mt/year is processed by plants based in PNG, Solomon Islands, and Marshall Islands. The largest markets for canned tuna remain the EU and US. Purse seine-caught skipjack from the WCPO is also used to produce the Japanese product, katsuobushi. Purse seine vessels with ultra-low temperature (-45 to -55°C) freezing capability also supply yellowfin for lower-grade sashimi products.

There are a range of developments and key issues which have impacted the WCPO purse seine fleet – some have emerged in recent years, others are long-standing: fleet expansion, Pacific Island countries’ fleet development aspirations, FAD management, sustainability, traceability and labour requirements, fisheries access, market access, EU-IUU Fishing Regulation, fish and fuel price fluctuations and changes to fisheries management and regulation.

Taiwan

The Taiwanese fleet and Taiwanese capital are major players in the WCPO. Since 2004, Taiwan Government has instituted a limit of 34 Taiwan-flag purse seine vessels. At the time of writing, there was also an estimated 29 Taiwanese beneficially-owned purse vessels operating under PIC flag (90% flagged to PNA countries), bringing the total fleet to 63 vessels. Fourteen vessels with significant Taiwanese investment also operate under US-flag.

Taiwan’s purse seine vessel ownership is primarily family-based; most of the larger family-owned operations also own and operate vessels in other fisheries, notably, distant-water longline and squid/ saury fisheries. The purse seine fleet (Taiwan flag and beneficially-owned) is relatively young, with between 50-60% of vessels less than 10 years old, four of which were constructed in the past 2-3 years.

In 2018, the Taiwan distant water purse seine fleet catch was around 193,000mt and ranged from 160,000-237,000 mt between 2013-2018. The majority of fishing takes place within PNA EEZs, with only 95 high seas days allocated to Taiwan flag vessels by WCPFC. Taiwan’s purse seine fleets, whether flagged in Taiwan or elsewhere, are essentially transhipment fleets that do not deliver directly to processors; the majority of catch is sold to global marine products trading company FCF and is delivered to Thailand or other major tuna processing centres for canning.

Taiwan has faced considerable criticism from NGOs and others on the crewing conditions of its distant water fleets. Most of the criticism has focussed on distant water longliners, but the purse seine industry also feels some of that pressure. Some segments of the Taiwan fleet have sought commercial advantage by obtaining MSC certification.

Korea

The Korean distant water purse seine fleet is modern, efficient and largely profitable; Korean vessels are the highliners of the WCPO purse seine fleet, with average annual catches of over 10,000 mt per vessel. Total catch by the Korean flag vessels ranged from 246,000 – 270,000 mt/year between 2014- 2018. The fleet fishes over a wide area of the WCPO, but with an increasing proportion of catch taken in eastern areas in recent years when El Niňo conditions have predominated. Fishing in high seas is restricted by the WCPFC to 207 days per year.

In 2018, the Korean-flag fleet consisted of 27 vessels and has been relatively stable for some years. Since 2013, the number of beneficially-owned Korean vessels involved in PIC joint ventures has grown to 14 in four countries, taking the total Korean-owned fleet to 41 vessels. The re-flagged vessels have typically been replaced by newly constructed Korean-flag vessels. Korean onshore investment in PICs has been limited, despite proposals developed for PNG and Solomon Islands. For the Korean flag vessels, 17 of the 27 vessels (63%) are less than ten years old. By contrast, the PIC-flagged joint venture fleet is ageing, with 12 out of 14 vessels (85%) over 20 years old.

With the exception of one vessel, the Korean flag vessels are all owned by three large companies; two of which are vertically integrated into processing, whereas the third supplies two separately owned Busan-based canneries under contract. All companies have diverse interests beyond tuna fisheries.

The fleet tranships nearly all of its purse seine catch in PIC ports. A portion of the transhipped catch is returned to Korean ports for delivery to five domestic canneries for processing (120,000-130,000 mt/year), with the balance (~ 170,000 mt) going to canneries in other countries, primarily Thailand, Vietnam and Ecuador. Most Korean purse seine companies are reported to now have at least some of their vessels fitted with PS-special ULT refrigeration capability to produce lower-end sashimi markets in Korea and Japan.

Sustainability certification and ecolabelling have yet to gain much traction in the domestic processed fish market. However, there are some moves from fishing companies to obtain third-party sustainability certifications (MSC and Friend of the Sea) for export markets.

Japan

The Japanese fleet, early pioneers of industrial purse seine fishing in the WCPO, is no longer a dominant fleet, but remains a stable presence. The Japanese fleet has been relatively stable in terms of vessel numbers in recent years, as a result of government restrictions on distant water vessel numbers (capped at 35 since 1997). The fleet is comprised of 28 Japanese-flagged vessels and five vessels operating in joint venture under the FSM flag; the majority of the vessels are older and smaller than competing fleets from China, Taiwan and Korea. Historically, the Japanese Government has strictly regulated the size of the vessels. However, this policy has been relaxed in recent years, allowing for several larger vessels to be constructed (1,800 GT). The Japanese purse seine fleet is an ageing one, with 17 of the 28 active DW vessels (61%) over 20 years of age. Ownership is quite diverse, with two companies owning five vessels each, and the remainder of the companies owning 1-3 vessels each. The Japanese distant water purse seine fleet continues to operate primarily in the western part of the WCPO; it only has 121 high seas fishing days.

The Japanese tuna industry historically was involved in onshore investments in processing, founding two important Pacific Islands processing plants that are still operational today (though no longer with Japanese involvement): Soltuna in the Solomon Islands and PAFCO in Fiji. However, presently, those in the Japanese fleet have expressed little interest in either onshore investments or in further joint-venture operations.

The Japanese fleet primarily returns to Japanese ports to offload, and as such, does not rely on PIC transhipment ports. Though the Japanese Government has relaxed requirements to compulsorily offload in Japan, the fleet largely retains the practice. The additional costs of returning to Japan ports to unload for most of the fleet are claimed to be partly offset by the reduced VDS access fees (fewer fishing days required), and access to better maintenance and repair facilities needed for the ageing fleet than available in Pacific Island ports.

The Japanese-flag fleet caught 177,000mt in 2018. The fleet continues to supply the Japanese market, which includes a broader range of product types in comparison with other fleets. These include: katsuobushi, sashimi and canned tuna. All Japanese vessels now have varying levels of purse seine special capacity for storing a portion of catch for sale to higher value markets. No Japanese purse seine fisheries are known to be seeking MSC certification or participating in PNA’s MSC program, likely a reflection of limited domestic consumer interest in eco-labelled product.

China

Since the early 2000s, the Chinese purse seine fleet has grown considerably through a combination of new construction and acquisition of used vessels. Vessels are either wholly or substantially owned by large state-owned enterprises or by private sector companies. There are currently fifteen vessels in the China-flag fleet operating in the WCPO, and an additional six beneficially-owned Marshall Island flag vessels, three of which were constructed in 2019. Fourteen of the fifteen China-flag vessels are currently chartered to Kiribati. The six Marshall Islands-flag vessels are associated with the Pan Pacific Foods Ltd. loining plant in Majuro, Marshall Islands. The total catch of the Chinese-flag and beneficially-owned WCPO fleet could be in the order of 150,000 mt/year based on current vessel numbers.

China government subsidies given to distant water tuna fisheries for operations (mainly fuel), replacement vessel construction and the building or expansion of overseas bases have encouraged increases in the fleet. As long as China requires a certain percentage of catch returned to China for processing by vessels receiving subsidies, and fishery access in PICs is available to Chinese purse seiners through bilateral agreements, joint fishing ventures and chartering, it is unlikely that Chinese firms engaged in the WCPO purse seine fishery will make any further large investments in processing in Pacific Island countries. The Chinese government’s financial support for the establishment of bases has been primarily taken up by its longline industry in FSM, Marshall Islands, Kiribati and Samoa.

Recently, the fleet has been fishing mostly in eastern PNA EEZs - Kiribati, Marshall Islands and Nauru. China has only 26 high seas fishing days; however, the Marshall Islands-flagged vessels have unlimited high seas access. With the exception of small volumes delivered to Pan Pacific Foods in Majuro, catch is transhipped in PNA ports. The production of China’s purse seine fleet is closely linked to China’s tuna processing industry, which processes purse seine-caught tuna into loins for export and cans for both foreign and domestic markets. There is currently no production of ULT PS-special yellowfin within the fleet, although two vessels have ULT capability. The 10% tariff imposed by the US on loins imported from China was increased to 25% in May 2019. It is believed that the net result of these increases is greater export of Chinese purse seine-caught tuna to Thailand. So far, the domestic market in China for canned tuna has not taken off despite efforts to encourage growth.

In recent years, China has been making a concerted effort to be seen as a law-abiding participant in the WCPO purse seine fishery. Harsh penalties have been instituted for infractions of China’s domestic laws, WCPFC management measures and other requirements.

USA

The US fleet has long been active in the WCPO. Since the 1980s, its fishing activities in the region have been facilitated by the US Multilateral Treaty, which provides the fleet with access to all FFA members’ EEZs for up to 40 vessels. Prior to the introduction of the VDS in 2007, the US fleet had declined from 40 vessels to around 12-14, largely due to increased competition from lower-cost Asian distant water fleets.

As the VDS was designed to limit fishing effort and increase access fees for all distant fleets fishing in PNA EEZs, the US Treaty appeared to offer a refuge from uncertainty, as its terms continued to offer unlimited fishing access in all Pacific Island Party EEZs for pre-negotiated fishing license fees. To take advantage of this opportunity, owners of approximately 16 vessels – primarily from the Taiwan fleet – were added to the US flag in joint ventures with US citizens around 2010. This reinvestment, along with US flagged vessels that had previously left the WCPO and returned to the Treaty, revitalized the US fleet to 40 operational vessels. By 2017, however, that number declined with 34 US vessels active in the WCPO. In the coming licensing period, a total of 31 US flagged vessels are expected. Eight vessels have been recently announced as being sold, citing uncompetitive conditions operating under the US flag and a lack of support from the US Government. If the sales are concluded, the US fleet will be further reduced to around 23 vessels. Operators within the US fleet have developed several responses to cope with changing access conditions under the US Treaty – purchasing some bilateral days in favour of multilateral fishing days, maximising high seas and US EEZ fishing days, re-engaging in the EPO fishery and leaving the US flag (through vessel sales and/or re-flagging). However, the future of the US Treaty remains uncertain. The fleet’s total catch volume has steadily declined alongside vessel numbers – in 2014 total catch was almost 313,000 mt; by 2018 this had declined to 165,000 mt.

The US fleet has two distinct operating models, with one segment of the fleet (the ‘old’ fleet) typically fishing further in the eastern portion of the WCPO to serve American Samoa’s processing sector (and for some, also EPO processors). The other segment (the ‘new’ fleet of Taiwan-built vessels) fishes throughout the WCPO and operates under a transhipment model, delivering to processing plants in Thailand and the rest of Asia and occasionally, Central/Latin America. The eastern high seas is a significant fishing ground, particularly for the ‘old fleet’, with 1,270 fishing days allocated.

Several non-state regulatory issues – including eco-labels and shifts in design to non-entangling and biodegradable FADs – are now firmly on the radar of US vessel owners. Vessels in both the ‘old’ and ‘new’ fleet hold MSC certifications for free-school caught skipjack and yellowfin. Members of the US fleet are taking note that social responsibility, particularly concerns over labour standards are gaining attention, though formal regulation is still in its infancy.

Philippines

The Philippine tuna industry was among the first to develop on a large scale in the WCPO. Today, the beneficially-owned Philippines purse seine fleet of 91 vessels is collectively the largest in the WCPO in terms of vessel numbers, with a total annual catch of over 300,000 mt. It is comprised of domestic purse seine vessels which fish mostly within Philippines and High Seas Pocket 1, Philippines flag vessels fishing mostly in PNG under distant water or locally-based foreign access arrangements and PNG-flag vessels beneficially owned by Philippines companies operating under charter to PNG-based canneries. These vessels are owned by four Philippines companies. In general, the Philippines flagged fleet is comprised of older vessels which are relatively small in size in comparison with other fleets, making it a relatively less efficient fleet.

Diverse Philippines tuna industry presence remains at the heart of the large PNG tuna sector, with around 60 locally-based foreign, PNG flag vessels and distant water purse seine vessels and ownership of four of the six operational canneries in the country. All of the fishing companies are key suppliers to canneries in the Philippines. Most of the plants in the PNG processing sector continue to operate well below capacity, despite the global sourcing component of the EU Rules of Origin, given that affiliated vessels export high volumes of catch to the Philippines. After several false starts and a crowded investment space, there seems little appetite to expand the Philippines involvement to other PICs, other than bilateral or multilateral fishing access.

Whilst the Philippines distant water fleet has not made a concerted as yet to move towards MSC certification, Philippines PNG vessel owners as a group are moving towards certification, independent of the existing PNA/Pacifical MSC certification.