This latest FFA report by my colleagues Elizabeth Havice and Liam Campling, gives us a very detailed view on the main brads, that “far end” aspect of the tuna world, to people like me at the 1st steps in the value chain.

As all of their work I’ve read, this one is good stuff. I quote here the executive summary. but as usual read the original!

This report provides FFA members with industry and market intelligence on the current status of the shelf-stable (e.g. canned) tuna processing industry. It offers a global overview of processing capacity (providing data on volume and value of activities), new developments and key issues shaping the sector. It then conducts a focussed analysis of five case-study firms (three ‘major’ and two ‘minor’) to demonstrate the range of industry dynamics currently in play in the sector and to draw out implications for Pacific Island countries.

The case study firms are: Thai Union, Dongwon Industries and Dongwon F&B, Bolton Foods, Princes, and Bumble Bee. Primarily through desk-based research, the analysis details operations, ownership and management structures, vertical integration such as brand ownership, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), major markets, financial performance, sustainability and labour initiatives, recent changes and future developments, WCPO business interests and links with Pacific Island countries.

Global Overview and Key Developments

Between 2008 and 2017, global tuna processing capacity (whole round and cooked loins) increased 12-13%. Over the same period, the total number of processing plants increased from 144 to at least 215. Whole round fish represents around 85% of raw material throughput and frozen cooked loins account for around 15%. Loins are mostly used by processors in the US mainland, Spain and Italy. Estimated global canned tuna processing capacity is around 13,700mt/day, requiring around 3 million mt of whole round fish (skipjack, yellowfin and albacore). In 2017, the top five canned tuna processing countries by volume were: 1) Thailand (3,490 mt/day); 2) Ecuador (1,635mt/day); 3) Spain (1,275 mt/ day); 4) Mexico (725 mt/day); and, 5) Philippines (510 mt/day).

Thailand remains the world’s largest canned tuna processor, accounting for around 15% of production. Thailand does not have a significant tuna fishing fleet and so relies heavily on raw material imports, mainly from the WCPO, which exposes Thailand-based processors to risk during periods of high tuna prices.

The European Union is the world’s largest market for canned tuna. The market is supplied by producers inside the EU, mainly Spain (67%) and Italy (21%), and by imports, especially from countries with duty free access. The top three foreign suppliers are Ecuador, Seychelles and Mauritius. Import volumes from the Philippines and from Papua New Guinea have increase by 48% between 2013-2017. PNG and Solomon Islands loin imports accounted for, respectively, 9% (12,093mt) and 5% (6,477mt) of the EU’s total loin imports; volumes sourced from Solomon Islands, largely for Italy, grew 64% between 2013- 2017. Given that the UK is Europe’s largest imported canned tuna market, there is concern that Brexit might have a negative impact for exporters accessing that market.

The United States remains the second largest shelf-stable tuna market. The market is supplied by two canning-only plants (i.e. that import frozen loins) in the mainland and from the US territory American Samoa, where whole round is also processed, and by finished goods imports from around 35 countries. The top three foreign suppliers are Thailand, Ecuador and Vietnam. Frozen cooked loin import volumes have declined since 2013, with Fiji as a significant supplier of albacore loins in the range of 11,000-12,000mt/year.

Canned tuna processors continue to intersect with several long-standing concerns. The industry continues to struggle with overcapacity, with a majority of plants continuing to operate below full capacity, while new plant investments and expansions continue. Cyclical, short-term raw material price volatility continues to place pressure on processors in periods of higher prices, especially those that are not backward integrated into trading or fishing. Efforts to strengthen tuna fisheries management across all four ocean basins have not yet yielded long-term tightening of raw material supplies and associated long-term fish price increases. Canned tuna processors continue to face increased costs of key production inputs such as cans and ingredients such as olive oil; such costs are largely absorbed by processors because of the difficulty of passing cost increases on to consumers. The global canned tuna industry has continued to consolidate through mergers and acquisitions (M&A), which have taken place within the tuna and other seafood sectors and for both shelf-stable and frozen products. The rate of M&As is expected to slow as the most attractive deals have been completed or blocked by anti-trust regulation. Supermarkets continue to dominate retailed canned tuna sales globally, with private label brands providing strong price competition to national brands.

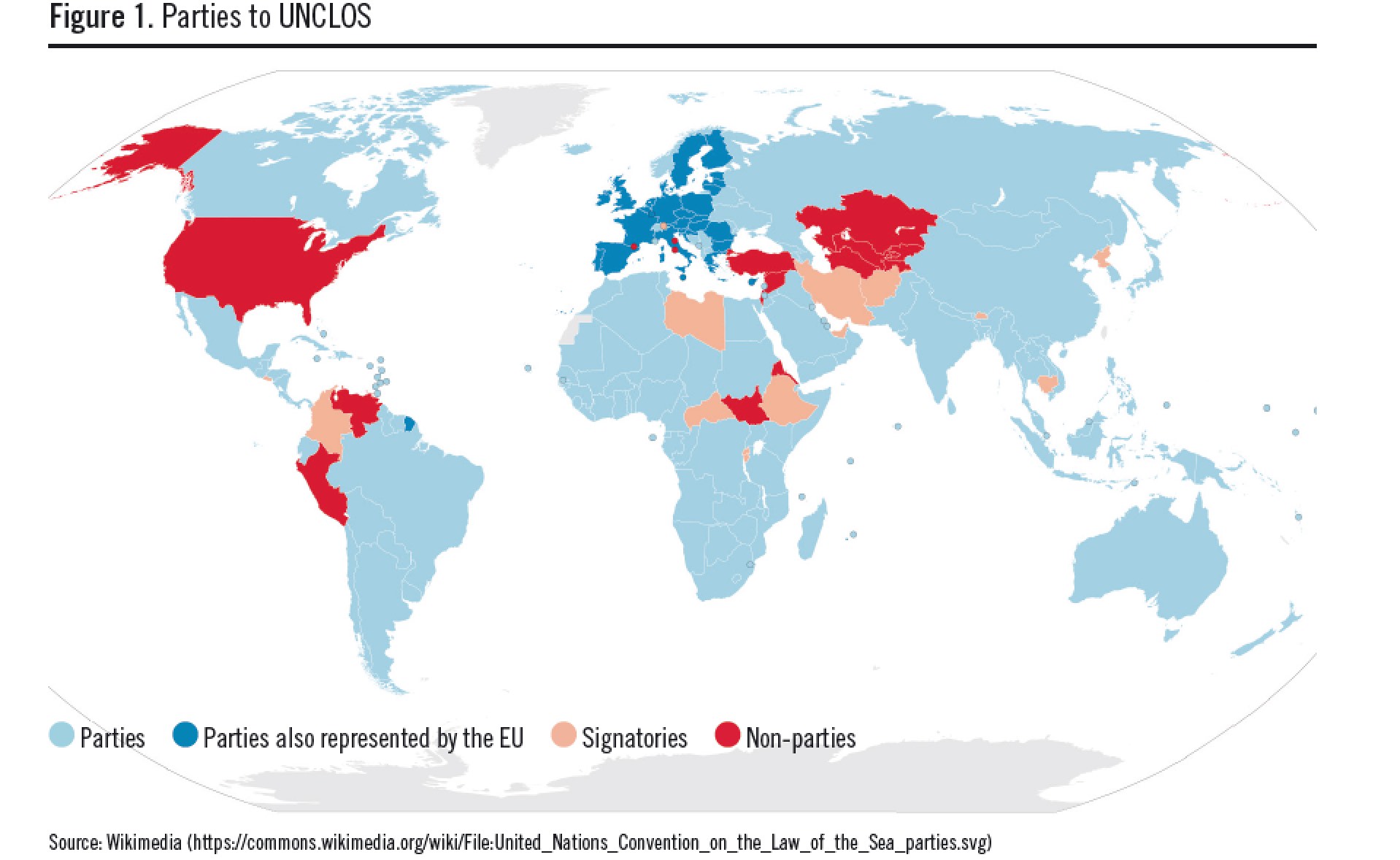

A number of countries with significant canned tuna and frozen cooked loin processing capacity that compete with Pacific Island processors in the EU market have concluded or are in negotiations for preferential trade agreements with the EU. The Philippines and Ecuador have gained duty free access to the EU and Vietnam has secured a quota for canned tuna and gradual liberalization of loins. Negotiations between the EU and Thailand, ASEAN countries and Indonesia are in various stages. The EU continues to issue IUU yellow cards as warnings that lack of compliance with the terms of the IUU regulation could lead to suspended market access. In the Pacific, Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, PNG and Tuvalu have been issued yellow cards and subsequently had them lifted when compliance was demonstrated.

Several developments have emerged in recent years. Initiatives related to sustainable fisheries, supply chain transparency, and ethical labour are now permanent fixtures in the industry, though each initiative varies in scope and aims. Processors and brand owners are developing innovative and value-added product lines that use less tuna raw material to combat high raw material prices and meet changing consumer preferences. Some processors are diversifying into high-quality pet food production to expand into new market segments and improve profitability. Firms are diversifying packaging materials and marketing channels (e.g. online platforms) to improve returns and reach new markets.

Case Study Firms

Thai Union is the largest tuna company in the world. Its business is focussed on three seafood divisions: shelf-stable seafood; frozen and chilled seafood and related products; and, pet care and other ‘value added’ products. Thai Union’s business model is highly dependent on tuna and ensuring stability of tuna supply is critical for the firm. It is not backward integrated into fishing, so to stabilize supply it maintains a large raw material inventory in cold storage and has recently developed a Global Procurement Team to centralize its purchasing power.

Thai Union’s core business is the manufacture of seafood for its own brands and as a private label processor for clients. It owns extensive processing operations in Thailand that contribute to a total of 17 production facilities in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia. Over the last 20 years, one of Thai Union’s key corporate strategies has been to forward integrate into brand ownership, notably with the purchase of Chicken of the Sea (1997) and MW Brands (2010). Forward integration has enabled Thai Union to capture a greater proportion of value through brand rents. Thai Union’s major markets are the US, Europe, Thailand and Japan, with 15% of total sales made in emerging markets. Thai Union is expected to look to organic growth, selective M&As, and product diversification to boost sales and growth. Thai Union is emerging as a leader in environmental and social responsibility, internalizing environmental and labour commitments and procedures and investing significant financial and human resources into monitoring and compliance.

Thai Union’s principal relationship to the WCPO is in its ongoing dependence on the region for tuna raw material supply, which is facilitated through Thai Union’s long-term relationship with the FCF trading company. Thai Union has increased its processing of co-branded Pacifical canned tuna for Northern European markets and the US market and is well positioned to supply growing demand for ‘sustainable’ canned tuna. Thai Union is a partner in Majestic Seafood Corporation in Lae, PNG, an investment that provides raw material supply to Thai Union, but that has not operated at full capacity.

The Dongwon Group is a sprawling South Korean industrial conglomerate. Through the inter-connected set of companies that make up Dongwon, the firm has comprehensive backward and forward linkages in the processing value chain and has the capacity to raise money to purchase supporting companies. Two of its subsidiaries are central players in the tuna processing industry.

Dongwon Industries Co., Ltd. is Korea’s largest deep-sea fishery company, owning 19 purse seine vessels. The firm has focussed on expanding vessel capacity and profitability, building seven new purse seine vessels since 2006, with two additional large vessels scheduled to join the fleet in 2018. These new vessels enhance annual per-vessel catch and are equipped with rapid cooling technologies and facilities to manage sashimi-grade handing and freezing. The vessels supply plants in Bangkok and sister company, Dongwon F&B’s processing plants. Dongwon Industries’ ULT longline fleet primarily supplies Japan for sashimi grade product. Dongwon Industries vertically integrated into brand ownership by purchasing Starkist (2008), the market leader in the in the US, and also owns processing facilities in American Samoa, Senegal and Ecuador. Starkist is also the leader in the higher profit pouch segment of the US market and is expanding into niche marketing and value-added products. Dongwon F&B Co. Ltd is a branded manufacturer that controls 75-80% of the Korean canned tuna market through ownership of over 16 brands and three processing plants. Dongwon F&B has high exposure to raw material price increases; the firm is presently working to expand further into the domestic market and broaden its reach to international markets and develop value-added products, emphasizing the health and convenience of its products.

The broader Dongwon conglomerate exhibits a high degree of vertical integration, accomplished in part through M&As, where Dongwon’s affiliates integrate with each other and create opportunities for the Group as a whole to expand market and product reach. Strategic M&As that support the Group’s tuna processing business include mergers with or acquisitions of firms that specialize in tin can production for shelf-stable products, logistics, online retailing of ready-made meals, tuna processing and diversified seafood products. Reversing a long resistance to eco-certifications, Dongwon Industries has made several moves into the MSC certification market. Starkist has initiated the MSC process for US flagged longline vessels out of American Samoa, and Dongwon Industries has initiated MSC assessments for its purse seiners in the WCPO (which make a high proportion of sets on free schools) and longline operations in the WCPO and Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO).

Dongwon has several important connections to the WCPO. Both Dongwon Industries and F&B are heavily dependent on the WCPO, particularly waters of the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), for raw material supply, and Starkist has a large processing plant in Pago Pago, American Samoa. Dongwon Industries has announced a collaboration to build a small tuna processing plant in Kiribati in an aim to secure access for highly competitive fishing days and market access to the EU (if rules of origin are met). It has also engaged in ongoing negotiations to build processing plants in exchange for access in PNG and Solomon Islands, though there has been no recent progress on these proposals.

Bolton Foods is part of Bolton Group – a large privately-owned company offering a wide range of consumer goods under five business units. Bolton Foods focuses on premium branded shelf-stable tuna products and has developed high quality product specifications. It wholly owns three canned tuna brands, holds shares in several other important brands and distributes tuna product to over 60 countries.

Since 1999, it has made several acquisitions to become more vertically integrated; diversified its portfolio of brands and processing operations geographically from Italy into other markets within and outside of Europe; and further secured access to raw material. Bolton’s purchase of the Saupiquet brand (1999) cemented its standing as the EU canned tuna market leader and integrated the firm into fishing with four large tuna purse seiners operating in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Supply from those vessels feeds non-branded processing plants in West Africa, Spain and Latin America that handle loins and finished goods production for Bolton. More recently, it purchased Calvo, acquiring Spain’s leading canned tuna brand and processing plants in Spain, El Salvador and Brazil, and a fleet of seven purse seine vessels. In 2013, it acquired a share in US global tuna trading company, Tri Marine, which strengthened its links to the WCPO and gave it access to supply, processing capacity, a niche brand in the US market and fishing vessels. Its 2015 it acquired Conservas Garavilla and its two brands, with presence in Spain, across the Americas and in North Africa, as well as processing plants in Spain, Ecuador and Morocco and four purse seine vessels.

Bolton also has processing capacity in Italy which relies on imported frozen loins. To retain competitiveness for processing facilities in Europe, Bolton pioneered the import of pre-cooked loins, and has continued to innovate mechanized canning facilities that require minimal labour. Bolton also sources some branded finished goods from processors in Spain, Thailand, Ecuador, Ivory Coast and Mauritius. It is presently focussed on growing its presence in international markets, expanding into online and convenience sales platforms. It continues to differentiate its products through premium quality and ingredients as well by developing value-added products. It has launched its ‘Responsible Quality’ programme, through which it undertakes a range of corporate social responsibility initiatives related to environment, health and labour. Partnerships with advocacy organization World Wildlife Fund (WWF) focus on sustainability and traceability.

Like other firms, Bolton is linked to the WCPO through its use of raw material from the region. It has direct links through its shareholding in Tri Marine, which owns a Solomon Islands’ flagged fleet of seven purse seiners and four pole and line vessels. Tri Marine is the majority shareholder of the Soltuna processing plant in the Solomon Islands, whose primary business is to process loins for Bolton. Tri Marine also owns six US-flagged purse seine vessels operating in the WCPO and Samoa Tuna Processors in American Samoa, which is presently not operating but leasing cold storage to Starkist.

Princes Group focuses on the import, manufacture and distribution of food and drink products to the grocery trade. It is a private company headquartered in the UK and owned by Mitsubishi Corporation; being a part of one of the world’s largest trading companies means that Princes has access to financial resources that enable it to act on M&A opportunities. It holds a wide portfolio of over 350 Princes’ own brand products, including Princes canned tuna, and also provides private label canned tuna for EU supermarkets. Over 70% of all sales take place in the UK, where Princes holds around 25% share of the canned tuna market, chasing Thai Union’s 35% market share with its John West brand. To improve profitability, Princes has reduced can size, and developed value-added products. Princes has high exposure to a concentrated number of buyers and is actively seeking new markets.

Princes is vertically integrated from canned tuna brand ownership into processing, with a major factory complex in Mauritius, making it a competitor to Pacific Island processors because of its duty-free access to the EU market. It complements supply with contract processing arrangements with firms in Ecuador, Thailand and the Philippines.

Princes is not planning any major changes and is remaining focussed on its existing core businesses. It is developing sales of value-added tuna products but remains constrained by price and promotional offers in the UK market in particular. Following poor performance on Greenpeace rankings, Princes committed to sourcing 100% of its supply from either pole and line fishing or purse seine fishing on free schools. Princes now sources MSC ‘wherever possible’ and is procuring fish from several MSC fisheries and several fisheries under Fishery Improvement Projects (FIP). Princes does not own boats, which makes it sensitive to raw material price fluctuations. It has no direct investments in the WCPO, but it is a leading partner with Pacifical and was the first UK brand to sell tuna from the MSC certified PNA fishery.

Bumble Bee is a manufacturer and brander of seafood products with a focus on tuna, ready to eat meals and a range of other shelf-stable and frozen seafood and protein products in the US and Canada. It is owned by Lion Capital, a private equity firm focussed on the fast-moving consumer goods sector. In the US, the firm markets products under the Bumble Bee and Wild Selections brands and is the US leader in canned albacore, which has higher value than light meat product. It sells canned tuna, as well as a wide range of shelf-stable seafood and chicken products. In overall tuna product offerings, Bumble Bee is number two in the US market, accounting for 25% of the category in value sales. Connor Bros. is the Canadian marketing arm of Bumble Bee. It owns the Clover Leaf brand, Canada’s market leader in canned tuna, as well as Brunswick, Sweet Sue, and several other brands that sell tuna, other shelf-stable seafood and protein products.

Bumble Bee is not backward integrated into vessel ownership. Rather, to secure supply it has developed a global sourcing and production strategy that focuses on white meat product. Bumble Bee sources white meat loins from Fiji (PAFCO – Bumble Bee managed plant) and Mauritius and light meat loins from Thailand and Ecuador (and very small amounts from SSTC in Papua New Guinea), for its Santa Fe Springs plant on the west coast of the US. In addition to processing for its own brand, the Santa Fe Springs plant co-packs for Chicken of the Sea; while Chicken of the Sea’s plant located on the east coast of the US co-packs for Bumble Bee. Bumble Bee also has a strong historical relationship with trading company FCF. Bumble Bee has pursued and been the object of several M&As in recent years. It has been pursued by private equity funds seeking to increase the value of the brand before selling it for a profit. Thai Union attempted to acquire Bumble Bee, an effort that terminated in 2015 as antitrust clearance procedures stalled and opened the door to unfolding price fixing revelationsamong the US ‘big three’ canned tuna brands. In the wake of the US price fixing scandal, Lion Capital is unlikely to sell Bumble Bee in the near term.

Future developments focus on sustainability, traceability and product diversification, and on jump-starting the North American market after a prolonged decline. It has recently launched a catch-to-can, consumer-friendly tracking programme. In its effort to boost the stagnating US market, Bumble Bee has emphasised the health and quality attributes of its products, differentiated its products from lower quality competitors, and developed value-added product lines, including a move into the freezer aisle facilitated by its purchase of Anova Foods.

Bumble Bee has several direct links to the WCPO. It manages the majority government-owned PAFCO plant in Levuka, Fiji, which supplies its mainland US plant with albacore loins. In recent years, it has offered PAFCO loans for cold storage and infrastructure upgrades, though high operating costs and supply concerns are ongoing. It has also purchased small volumes of loins from SSTC in PNG. Its 2013 purchase of Anova Foods deepened links to the Pacific as the firm sources from the Cook Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia, in addition to Indonesia. Anova has initiated sustainability initiatives in those locations. Bumble Bee has also announced a deal to bring Pacifical products to the US. Several exploratory initiatives, including for a loining plant in Samoa and for processing in Vanuatu, are yet to come to fruition.

Implications for Pacific Island Countries

Collectively, the five case study firms reveal a diversified set of strategies in the shelf-stable tuna sector. While all of the firms use M&As to expand the scope of their business portfolio, they do so in different ways and for different reasons. In some cases, this has deepened horizontal integration, expanding a firms’ traditional strength by, for example, purchasing processing plants in strategic locations, or acquiring brands that offer access to new markets. In others, they have enabled vertical integration outward from the processing node of the canned tuna value chain into direct marketing, branding, trading and/or fishing. Each firm has employed these strategies in distinct ways and to various extents.

The cases studies offer evidence of growing consolidation among leading firms with core competencies in processing and branding, though the pace of consolidation is likely to slow with many large mergers now complete or blocked by anti-trust regulation. There is a high degree of vertical integration between processing and branding, with some, but not all firms, also backward integrating into trading and/ or vessel ownership to secure supply. The large investments that several firms are making into brands offers evidence of brand rent in shelf-stable markets. This has relevance for efforts from Pacific Island countries, like Pacifical, to develop links into branding to improve returns in the region.

These features also relate to the degree in which each firm has exposure to raw material price, that is, the extent to which a firm’s profitability is influenced by fluctuations in canning-grade tuna price movements. Firms that are vertically integrated into fishing have lower exposure and may in fact benefit from raw material price increases. Processing-focussed firms with high exposure to raw material prices have adopted strategies such as investing in cold storage to hedge against such risks.

Several of the firms reviewed are financialized – that is, intertwined with transactions in which profit making and risk hedging occurs through financial channels, rather than only through trade and commodity production. Access to financial capital enables these firms to make strategic investments, counter hostile take-overs, and weather unexpected costs that might hit competitors with access to fewer resources.

In addition to these firm-specific dynamics, the analysis reveals several broader dynamics that are impactful industry-wide and have specific implications for Pacific Island countries.

As a group, branded-processors are able to weather fluctuations in raw material price, with variation among them. This might be explained by a combination of factors including (a) cross-subsidisation (e.g. boat ownership and/ or other business segments); (b) greater focus on cost control and/ or synergies from M&As; and (c) investment in new process technologies and value-added product innovation. There has been relative stability in aggregate branded-processor profit. This may relate to these firms’ market power and related ability to squeeze non-branded suppliers (of which there are many, in sharp competition among one another), capture brand rents, and ad hoc strategies such as the recent US price fixing scandal and the prior role of the Pacific Operating Committee in stabilizing canning-grade albacore price. The firms appear to have factored in, and adapted to, the PNA Vessel Day Scheme, and related WCPO initiatives such as high seas closures and limitations on and charges for FAD fishing.

Processing firms, as they form various degrees of forward and/or backward integration, continue to develop and rely on and create global procurement and production strategies to secure both raw material supply and market access. These strategies continue to be formulated around trade policy, labour productivity, and resource access.

Product diversification and development of value-added products is finally becoming more established in many of the major and emerging markets. If value-added products take fuller hold and spur market growth and improvements in profitability, all of those involved in the global value chain – including Pacific Island country resource owners and processing firms – will compete to capture the value added. There is an opportunity to increase yellowfin volumes caught from the WCPO – and/or to direct existing yellowfin that presently gets mixed into ‘light meat’ products – to substitute volumes supplied from the Indian Ocean to high value EU market segments, given the IOTC yellowfin stock is overfished and subject to overfishing, while WCPO stocks remain healthy.

One of the most significant recent developments in the canned tuna sector is the increasing focus on sustainability, eliminating IUU fish in supply chains, traceability and ethical labour practices. Many such efforts began as a result of external pressure from advocacy organisations and resulting demand from buyers. They have now been internalised within many firms, and/or are being developed through collaborations between firms and advocacy groups. Generally, these movements will present both costs (auditing, management and production changes) and opportunities (reputational gains, market access, potential price premiums) to fishing fleets, processors and branding and retail. It is not yet clear how these will shape raw material prices and related access fees.

Pacifical stands to be an important supplier of certified product but will also face increasing competition from other MSC certified fisheries as major fishing and trading companies (Tri Marine, FCF, Dongwon) obtain their own certifications for purse seine fishing operations in the WCPO. These competing certifications will likely have a different pricing structure which is more palatable to brand owners (i.e. MSC premiums payable on the cost of raw material (i.e. $/tonne) rather than the Pacifical model where a premium is charged on finished goods (i.e. % of gross sales value)). Competing certifications will not have compulsory labelling requirements, which is a key feature of the Pacifical model.

PICs needs to continue to conduct careful analysis of proposals from foreign companies expressing interest in investing in onshore processing developments. Companies considering making an onshore processing investment are usually doing so as a means to obtain beneficial access to fishing through guaranteed and/or discounted fishing licences. There are multiple cases of companies expressing interest in processing facilities in various Pacific Island countries which have not yet or are unlikely to come to fruition.