I love when things align, and this is one of those cases.

On one side, the people from InfoFish has been very kind to asked me again to talk this year at the world tuna forum,. This will be my 6th time speaking there, and they have always supported me view and are keen users of my ‘people” pictures so instead of a talk about my usual fare of CDS, PSM MCS and compliance stuff, I proposed talking about people and this was my pich:

In the tuna world, there have been significant advances in sustainability, management and quantification of IUU fishing. We have RFMO’s conservation and management measures that look after the long-term sustainability of tuna catches and the welfare and safety of sharks and rays for example. Yet almost no framework that looks after the key factor of why we have a tuna fishery: its people. This presentation will not try to sell you anything, nor convince you that this or that private scheme profiting from this sad situation will solve the problem. This presentation intends to present the human side of fisheries, the faces of only a few of the thousands that will never be at this conference, but the ones that are out there on vessels and wharves allowing us to be here. The presentation will discuss who should legally be looking after their interests and welfare, what good things are happening and how the failures of responsibility by some developed flag states are pushing developing coastal and port states to try to find solutions. And finally the hypocrisy of how we, as a worldwide industry, require and expect excellence from all of them, yet we offer and pay mediocrity at best.

And they liked it! So I was planning to get my best pictures and finds based on my work for FAO writing the Draft Guidance on Social Responsibility in Fish Value Chains and the recent paper I co authored into a presentation, and legally anchor it in my present learnings in UNCLOS training I’m working my self into here in Rhodes.

And then yesterday, this absolutely amazing paper I been waiting for a while by my aquintance Dr. Penelope Ridings came my way. "Labour Standards on Fishing Vessels: A Problem in Search of a Home?" and really is a crucial reading for those of us working on the fisheries and fisherman labour rights areas. She is our region top legal scholar in all things law of the sea, RFMOs and fisheries… and her paper is by far the clearest and most comprehensive read I had in this topic, which has been close to my work (and frustrations) since writing the Draft FAO Guidance on Social Responsibility in Fish Value Chains that bounced at COFI FT

The only bit I wish someone explores (with her depth of understanding) is the “immigration” type component from foreign workers in fishing vessels. In my personal case I had a working permits, then visa when I started working in the fishing industry in NZ that gave sort of “equal” rights to kiwis… yet this is not the case in many countries. In fact the biggest cases on labour abuse happen on vessels of flag states that run a two tier systems for foreign workers (one for people coming to work in their territory - via immigration , and a different for people in the their vessel - generally not regulated by anyone) which i think is aberration.

Needless to say, I will quote a lot of her writing (as is done in a manner and clarity I’ll never achieve) in my presentation in Bangkok, but here I wanted to quote some of the main issues I absolutely agree with her and been part of my thinking over many past blogs on this topic. As always: read the original if you have time.

The legal and jurisdictional framework for addressing labour conditions on board fishing vessels is centred on art 94(1) and art 94(3) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS’).13 These articles place responsibility on the flag state of a vessel for, inter alia, ‘administrative, technical and social matters’ on the vessel, for ensuring safety at sea, and for ‘the manning of ships, labour conditions and the training of crews, taking into account the applicable international instruments’.14 Much of the international discourse on labour conditions on fishing vessels focuses on the question of how to enhance mechanisms to ensure that the flag state properly fulfils its flag state responsibilities and how states may exercise complementary jurisdiction.

It should be emphasised that each of the various international and regional agencies involved in seeking to address labour standards on fishing vessels is making best efforts to address the issue within its mandate. The problem is not with the lack of individual effort of organisations but with the fragmentation of these efforts and the difficulty of dealing with the issue in a coherent and holistic way.

The theory of international organisations is traditionally based upon functionalism — the idea that international organisations exist in order to exercise functions delegated to them by member states, and states cooperate in order to give effect to certain functions.62 The review of the applicable international instruments and organisations engaged in seeking to address labour standards on fishing vessels highlights the deficiencies with a functional approach to such international issues. The tension between state sovereignty and the function of international organisations creates a situation where members of an organisation may question the competence of the organisation to deal with a particular matter.63 A functional approach is not able to respond effectively to cross-cutting issues and produces international legal rules which are fragmented and lack coherence. It has, in the words of Jan Klabbers, ‘passed its sell-by- date’.64

In part this is due to the very multifaceted nature of the problem. The international legal norms with respect to conditions on board vessels are based on flag state responsibility and control. It is incumbent on the flag state to construct vessels with appropriate standards, to ensure that the owners and masters of vessels adopt and apply proper labour standards on vessels, and to verify and enforce compliance with those standards. Yet flag state enforcement is frequently lacking, particularly, but not only, on vessels flagged to countries with poor compliance records. In many cases crew on fishing vessels find positions through recruiters or brokers in their home countries.65 Yet the home state may not regulate manning or recruitment agencies, leaving their nationals subject to unscrupulous dealers. The capacity of other states to exercise jurisdiction in respect of labour conditions and abuses on fishing vessels, including coastal states, port states and home countries of crew, may be limited.

The issue is not necessarily due to a lack of international agreements but more to the lack of binding rules applicable to a large number of flag states and, importantly, inadequate compliance with those international instruments that are applicable.66 There are very few ratifications of the major international treaties designed to address labour standards. Even if the international rules exist, there is an apparent inability or unwillingness on the part of flag states or other states with potential jurisdiction over such vessels to monitor compliance or enforce those rules.67 This is compounded by the use of flags of convenience to avoid more stringent legal requirements. There is also little demonstrated push to enforce the rules at a national level.

There is a tendency for the complex jurisdictional issues to be used as a justification for inaction.68 The flag state cannot exercise jurisdiction over persons outside its control, such as recruiters or brokers in the home country of fishing crews. It has also proved difficult to take action against the agencies involved in the recruitment of migrant fishers.69

The effectiveness of international labour standards depends on the degree to which these standards are incorporated into domestic legislation and enforced by domestic authorities. The fact that the exploitation of fishers takes place outside the territorial jurisdiction of a state and within the jurisdiction of the flag state poses evidentiary and jurisdictional challenges. It is difficult to investigate incidents which take place on board vessels in distant waters. Crew may be intimidated and not wish to come forward due to potential retribution. Fishers on distant water fishing vessels spend long periods at sea and may not visit their home countries or other ports very frequently. This may place them at the mercy of the vessel master and severely limits their ability to protest their treatment. Even where crew do protest, other countries face jurisdictional challenges in taking action in response.

As a result of this, attention has turned to whether other states, in particular port states, may also play a role in raising and applying minimum standards. The nine regional memoranda of understanding on port state control are geared towards inspections of ships for safety standards and pollution and do not provide an easy vehicle for inspections relating to labour conditions on board.70 However, the ILO Work in Fishing Convention provides optional port state jurisdiction for states that are party to the Convention to investigate, report on and take steps to rectify alleged violations of the Convention on ships in its ports, even in cases where the flag state of the ship in question has not ratified the Convention.71 The same potential occurs with the Cape Town Agreement which provides minimum standards for accommodation and other conditions on fishing vessels. If more states ratified these two treaties, it could open up the possibility of using port state measures on the basis of the ‘no more favourable treatment’ requirement.72

Another fundamental issue is that the existing legal instruments keep the issues of human rights and labour abuses in the fishing sector and IUU fishing separate from each other with little coordination between the various agencies involved.73 This is compounded because labour standards are usually managed by the labour ministry, while fisheries ministries do not have the power, expertise or mandate to deal with labour issues.74 There is a fragmented approach to the development of international rules and a resulting lack of coherence between the rules. The rules have been developed in silos and are inadequate to address a multifaceted problem which often takes place in areas where jurisdiction is difficult to exercise.

The functional approach to international organisations, where each agency is only able to take action within its specific mandate, and states are reluctant to expand the scope of an agency’s mandate, is the biggest impediment to effectively addressing labour standards on fishing vessels. The following section examines the responses that have been used to respond to these deficiencies.

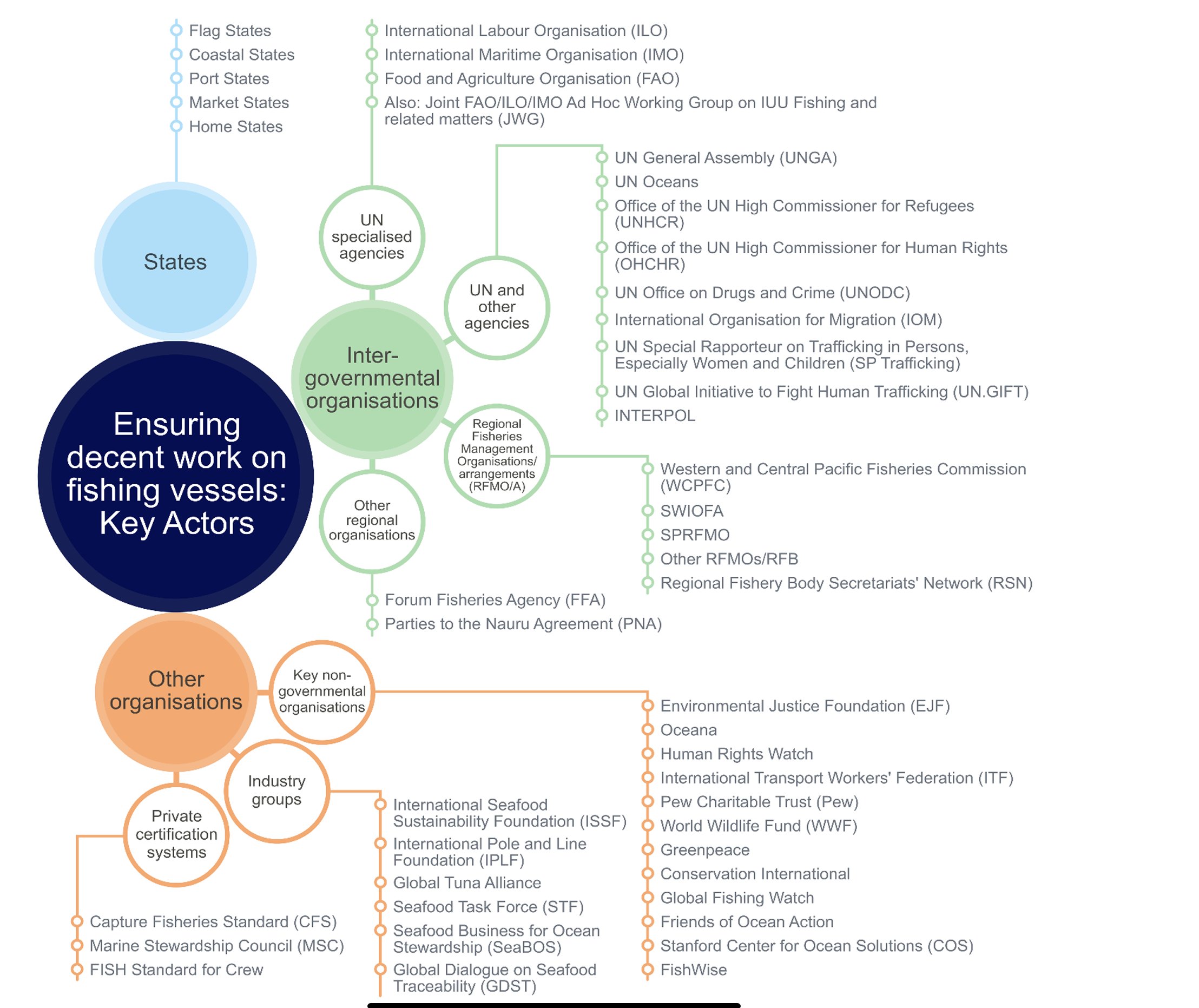

A range of states and intergovernmental, non-governmental, industry and private certification organisations are actively engaged in seeking to address labour conditions on fishing vessels. Figure 1 illustrates this complexity. The difficulties inherent in an institutional framework which is regulated by so many different international organisations has been highlighted previously.117 However, it is not simply the plethora of actors involved, but the lack of serious engagement at a political level and the use of jurisdictional issues as an excuse for inaction.

Figure 1: Key Actors in ensuring decent work on fishing vessels

It does not need to be this way. New Zealand demonstrated a political commitment to taking action to address labour conditions on chartered fishing vessels and resulting jurisdictional issues by passing legislation requiring foreign-owned vessels to be flagged in New Zealand before being able to fish in NZ waters.

Calling for ratification of international instruments is not enough. There needs to be exploration of the reasons why the Conventions are not being ratified. It may be more constructive to encapsulate expected action in a single soft-law instrument to provide a coherent legal framework and which could be used to raise labour standards while acknowledging the link between poor labour standards and IUU fishing. This could lead to a UN General Assembly resolution which provides a set of concrete actions for flag states, coastal states, port states, migrants’ home states and recruiting agency states to follow. A joined-up and coherent legal framework would make complementary action by RFMOs more feasible. It is through such soft-law instruments that regulations, procedures or practices concerning labour standards on fishing vessels can become ‘generally accepted’ within the terms of art 94(5) of UNCLOS.134 As Judge Paik has said, it is important to read flag state duties under UNCLOS in a way which recognises that ‘flag State jurisdiction and control have evolved to cope with new issues, reflecting the changing needs of society and the new demands of the time’.135 This may mean that a greater range of states can play a role in ensuring compliance with internationally accepted norms to improve labour conditions on fishing vessels.

Particular attention should be placed on the role of port states and coastal states. Port states can complement flag state responsibility and make an important contribution to ensuring compliance with international rules. It is generally accepted that port states do not exercise jurisdiction over affairs that are internal to the vessel and that do not affect the interests of the port state.136 However, ‘[w]hat constitutes “internal affairs” of the ship and “interests” of the port State … depends to a large extent on specific circumstances as well as on the evolving dominant views in the international community’. In light of the interest of the international community in ensuring compliance with basic human rights norms, there is a role for port states in inspecting vessels and identifying instances of human rights abuses. This may be akin to an expansion of port state control to encompass labour conditions. This could provide an opportunity to integrate and ‘mainstream’ maritime labour concerns into the international regimes relating to ship safety and security and environmental protection.

Similarly, coastal states have the right under art 62(4) of UNCLOS to require that nationals fishing within its exclusive economic zone comply with coastal state laws and regulations.138 Nevertheless, there is a legal tension between this and art 94 of UNCLOS, which places responsibility on the flag state for the internal order of the vessel.139 Any lack of legal clarity could be one of the elements addressed in any soft law instrument in order to provide appropriate legal frameworks for both coastal state and port state action. At the national level, a new instrument could promote the intensification of state regulation of labour conditions on fishing vessels. It could reinforce the need to improve flag state implementation, compliance auditing and enforcement. It could also address the need for action to be taken in respect of recruiters and brokers in the fisher’s home state or in third states.

The search for a home

Labour standards on fishing vessels is a multifaceted, multi-jurisdictional problem involving a wide range of states and non-state actors. A multilateral initiative is a potential avenue and catalyst for enhanced action. However, more is needed than just expression of good intention or appeals to states to ratify relevant international conventions. Concrete actions need to be taken by states and businesses, those actions need to be coordinated, and there needs to be a follow-up mechanism to ensure that expectations are fulfilled. Fundamentally, a multilateral initiative within a UN framework would help to make the issue a global political priority and would enhance cooperation among the many involved actors. It is only through a UN process that such a multifaceted and crosscutting issue can be addressed in a concerted and coordinated manner. It can cut through fragmentation, circumvent the functionalism of international organisations and harness the necessary political will. A UN process can provide a blueprint for making a meaningful contribution to addressing the serious concerns over applicable labour standards on fishing vessels.