I knew about the Stockholm Resilience Institute, because a friend from FAO went working there, and they always seemed to me as a organization with “fresh” thinking. A recent paper they produced just reinforces that concept. I don’t know any of the authors, but hopefully they don’t mind I quote them and present their interesting publication.

They start with the ecology concept of “keystone species”, that are those …that have a profound and disproportionate effect on communities and ecosystems and determine their structure and function to a much larger degree than what would be expected from their abundance… And they adapt this concept to identify “seafood companies” that take a similar role in the global seafood industry “ecosystem”.

They recognise that globalization of seafood trade has led to industry consolidation, with large and vertically integrated transnational corporations operating across entire supply chains from production through to retail. These transnational seafood corporations play an important role in linking distant species and ecosystems to major markets and consumers. At the same time their activities may influence important species and the dynamics and resilience of the ecosystems on which their seafood harvesting and production ultimately depend.

Furthermore, the authors realize that the role of global actors like transnational corporations has received limited attention in studies of ecosystem management and in particular marine ecosystem management. Existing analyses of global fisheries operations have focused on the role of individual major countries, rather than transnational corporations.

Therefore, in their paper, they analyze whether or not a keystone pattern can be observed in the relationship between transnational corporations and marine ecosystems globally, from a combined ecological, economic and policy perspective. If such actors operate analogous to keystone species, they would not only have a disproportionate ability to steer the direction of the seafood industry but also to shape the world’s marine ecosystems and how they are managed.

To do that this, they go trough and extensive bibliography and communicate with a very broad amount of people (many of them i do know) as to estimate the role of these largest companies in global fisheries catches, and they investigated their activities in relation to the largest and economically most important wild-capture stocks, representing whitefish, tuna, and small pelagic species. And then they a similar exercise with aquaculture species.

Furthermore (and I find this really insightful), they studied participation in globally relevant institutions as a proxy for the potential of the companies to influence fisheries and aquaculture policy and management. They quantified the number of occasions that a company was registered as a participant during the meetings of the thirteen Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), using the most recent meeting documents from the main governing body of these RFMOs, including five tuna RFMOs. They also reviewed company-specific membership in global industry organisations present in several of these RFMOs, and the role of the investigated companies in establishing, or the extent they were members in three international organizations identified as important industry initiatives for aquaculture management and certification (ecolabels).

Their results are quite staggering… They identify 13 companies (representing only 0.5% of 2250 registered fishing and aquaculture companies worldwide) that have a combined annual revenues corresponding to 18% of the global value of seafood production in 2012 (US$ 252 billion).

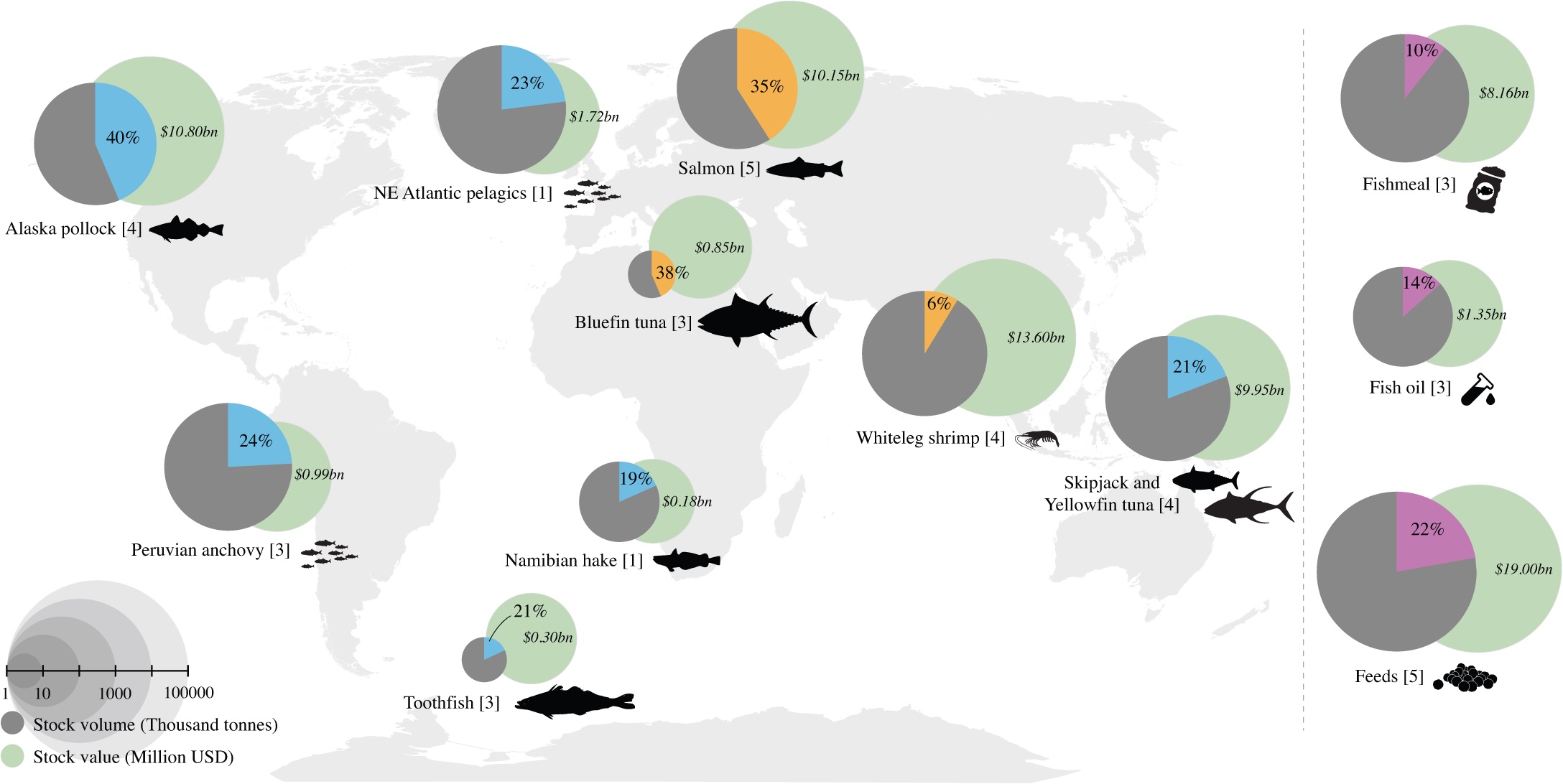

They represent 11–16% of the total global marine catch, and control an estimated 19–40% of several of the world’s largest or most valuable capture fisheries, including three of the most important wild-caught stocks used for human consumption: Alaska pollock (the largest whitefish stock), skipjack and yellowfin tuna (the largest tuna stocks used for the canned tuna and sashimi markets).

They produce 10% and 14% of global fishmeal and fish oil volumes respectively and 22% of global aqua feeds (including 68% of the salmon feeds and 35% of the shrimp feeds).

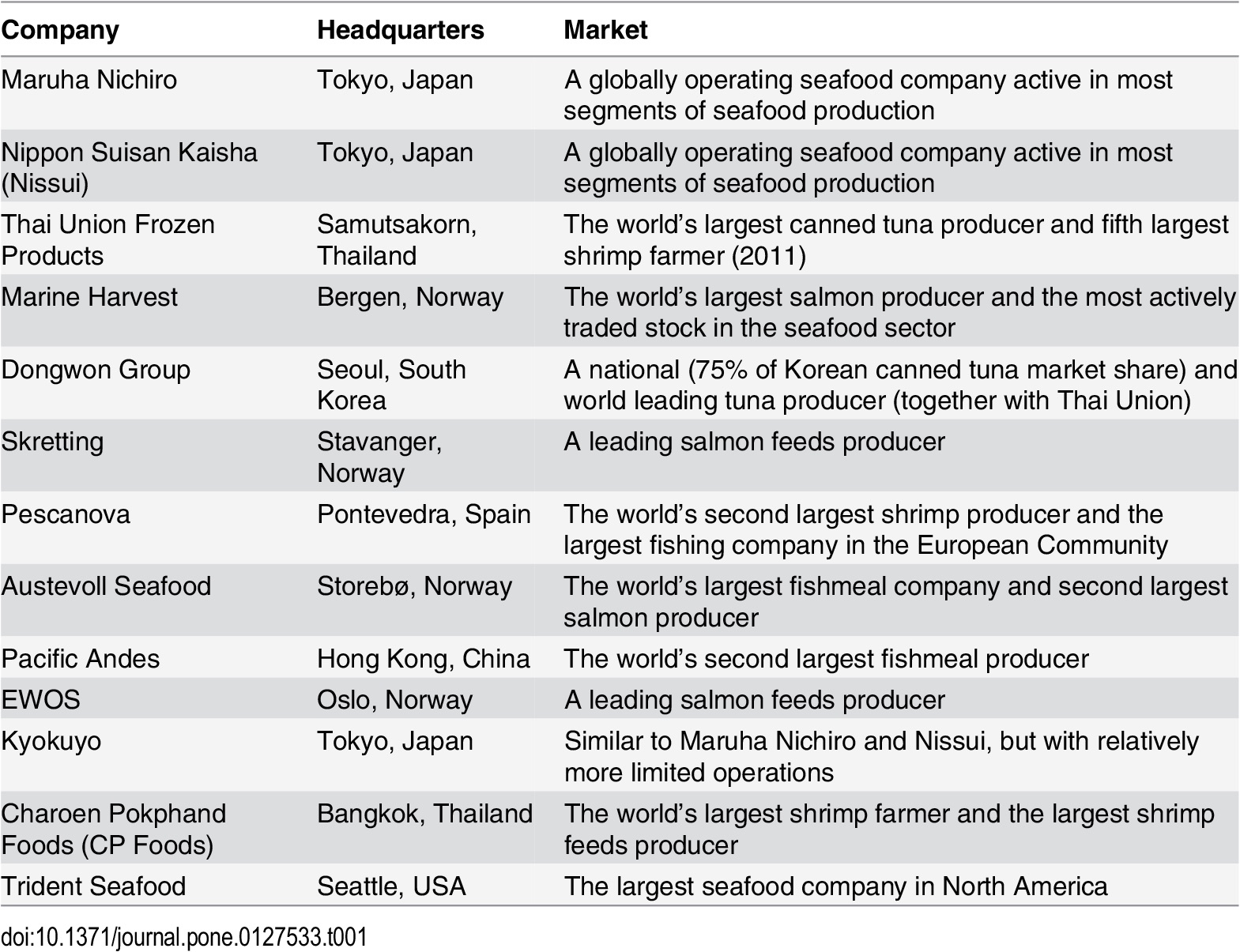

These “keystone companies” are:

These transnational corporations are catching, farming and handling more than 208 species from 974 subsidiaries and associates operating in 102 countries and territories (see in the figure below). They are each highly connected and act as key nodes in the global seafood production system.

Global networks of operations. Heat map illustrating the number of keystone actors operating in each country and the respective number of countries in which each company operates (blue circles) as well as the total number of subsidiaries of that company (purple circles). Company headquarters locations are indicated by the corresponding numbers on the map.

Their hold on the key seafood commodities is as well very well illustrated in this paper.

Regional fisheries of global relevance. Globally important wild fish stocks by volumes (grey circles with blue wedges), aquaculture production volumes (orange wedges), and global fishmeal, fish oil and aqua feeds (salmon, shrimp and whitefish feeds combined) volumes (purple wedges), and their corresponding economic value (green circles). The proportion of each stock controlled by the keystone actors is indicated by the size of the wedge. The number of companies active in each stock is shown within brackets.

They investigated as well, to what extent the globally connected actors participated in policy processes and found that three of the investigated companies were among the few (10%, n = 145) that were identified as active in more than one RFMO. They were active either as observers or as members of national delegations. The Korean company (Donwong) was the most active company overall, participating in six RFMOs. In addition to direct representation by the parent company and its subsidiaries, keystone actors are also indirectly participating in RFMOs through influential industry organisations. These companies also work directly with governments in a number of countries including small-island developing states in the Western Central Pacific, to secure access to the tuna resource.

The identification of keystone companies can have substantial implications for fisheries and aquaculture policy and management, as they play a central role in relation to global fisheries catch volumes and dominate several of the world’s largest wild capture fisheries.

The major wild caught species harvested by these companies are not only globally important resources for the seafood industry and consumers, but these species all individually play important roles in marine ecosystems (e.g. operating as predators or prey) and contribute to the structure, function and resilience of their respective ecosystems. Fishing for such species can have both direct and indirect effects on associated species and ecosystems, and as well impacts the production capacity of predatory fish in aquaculture is directly connected to marine ecosystems through the inclusion of wild fish in feeds (primarily small pelagic species). Salmon and shrimp are major consumers of aqua feeds (18% and 20% of global production volumes respectively.

Not only do these companies have the ability to shape ecosystems—they also actively participate in policy-making. The ability of non-state actors, such as transnational corporations, to influence policies can be directly correlated to their degree of participation in global (and local) governance.

Globally networked and vertically integrated companies, with an ability to influence policymaking, are resilient to disturbances that critically affect the survival of smaller companies, including financial system crises and instability, currency fluctuations, increasing fuel prices or changing fish stock dynamics.

The global connectivity of keystone actors provides them with a unique overview that enables them to know how, when, where, and with which company to strategically prioritize harvesting and sourcing activities. As keystone actors are critically dependent on a continuous supply of marine products, such global scanning ability ensures efficiency of production and consistency in resource supply. Keystone actors have historically increased their connectivity, analogous to the “rich-get richer” dynamics in other real world networks, through strategic mergers with major market or quota holders or via direct acquisitions.

As an example, Pescanova, the 7th largest company in 2012, went bankrupt in 2013, but was, due to the resilience resulting from its global connectivity and diversification of activities (active in wild capture fisheries worldwide as well as in aquaculture), able to maintain its operations and trading activities despite the bankruptcy.

What I find really “fresh” about this research is not the “naming” exersice… but the fact that we have always focus on nation states (either Flag, Coastal, Ports) as the key players which traditionally formed the basis for governance of fisheries resources and the majority of existing institutions are designed around this assumed reality, as are global fisheries statistics.

This study reframes the responsibility for fishing in terms of transnational corporations, illustrating that 13 companies handled around 10 million tons of wild capture fish in 2012, whereas only 23 countries caught >1 million tons of wild fish that year. Several fishing companies are thus larger than most nations and at the same time take part in decision- making bodies for these resources.

Perhaps we should think how twitch a bit the governance models, and have NGOs focussing their pressure to engage them in sustainability on a concerted campaign with governments, consumers, employees, competitors, investors or financial institutions.

Again, click the link for the the original paper: Transnational Corporations as ‘Keystone Actors’ in Marine Ecosystems if interested.