And as usual involves people with money and influences on one side and poorer people that want the same than the other… as well a lack of morality on both parts. There are plenty of examples of so-called “transparent countries” getting into this shit (see Iceland in Namibia, recently or one that almost costed my job back in 2011 from a Dutch company operation in Peru).

But definitively Flag of Convenience FoC (open registers) and tax heavens does play a role on this, and I wrote about them, hence I do have an interest in the topic so when I see papers (not that I have lot of time to read them) that deal with these issues I give them a go, and I quite liked this one from a group of researchers from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York

Is not an easy topic to tackle, and I like that they make a point that I have seen made before, and is that a subset of FoC is States which were considered to exhibit consistent patterns of failure in compliance with international obligations, defined as ‘flags of non-compliance’, were more common within the group of IUU vessels.

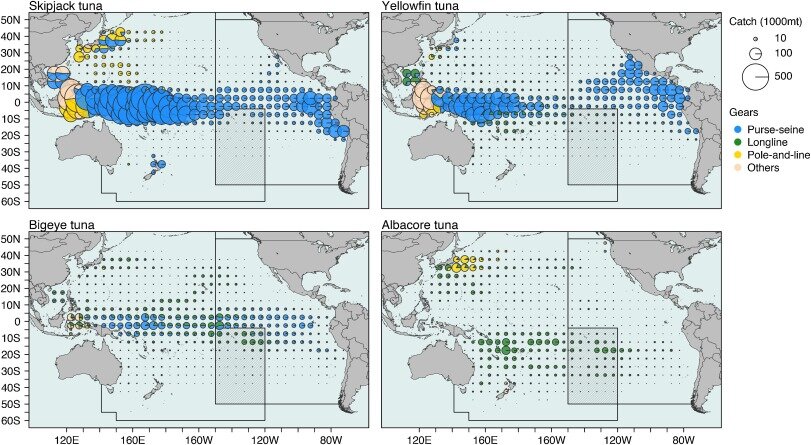

But also they go into some detail into the cases of fishing vessel operator that register under a foreign flag to gain access to fishing areas and resources as it increasingly happened in the Pacific. This strategy is perfectly legal and both socially and economically justifiable, though sometimes doesn't really work as everyone hoped.

The flagging is normally achieved via joint-ventures, where a foreign company partners with a local company or a flag-State government to jointly carry out fishing operations, the vessels that are owned by joint-ventures can apply locally for cheaper licenses, and these arrangements may also qualify them to register under a local flag despite being partially or fully owned by foreign entities. In principle, the participation in joint-ventures has been defensible as it can be a means for coastal countries that lack capital, infrastructure, markets, and other capabilities, to develop their own industrial fishing industries under the principle of domestication of the fleet.

Now in practice, a lot of issues have emerged, when the more experienced foreign partners have used financial manipulations to evade a fair sharing of profits or losses or directly left huge debt on the vessel for the country to take care or promises of national involvement in terms of crewing never happens. I have lost count on the amount of time I boarded “domestic vessels” where only 3-4 people on board are nationals of the flag state (to be honest the worst case scenario are the USA flagged PS fleet in the Pacific, where only 1 US citizen is required – the paper captain), but also if I want to talk to the “responsible” for that domestic vessel in the country where I’m working… I have to send an email to Asia.

And this leads me into a little-discussed in academia, but huge (in my opinion) issue of “conflict of interest”. When the joint venture involves the coastal state government (usually the fisheries authority!) who at the same time have the enforcement power… So the incentive for compliance gets diffused when in principle, they have to apply fines or prosecute a vessel they are part owners.

Anyway I paste below the parts I like the most from the intro, the discussion and the conclusion, but as I always advice, read the original! If you don't have access to the journals (like in my case!) I have not yet meet an author that would not send you a copy if you ask nicely, or a via a friend in universities or regional organizations that would flick you a copy… also (and depending your morals) there are grey ways to bypass the paying for articles.

Intro

In an attempt to examine the factors associated with the desirability of FoCs, we collected data from a variety of sources on a total of 38 factors (henceforth, variables). The data were collected for two different years, 2013 and 2018, separately, and the analyses were conducted accordingly. The 2018 data were the latest available data at the time of the writing of this research, and the 2013 were retrospectively collected and analyzed in order to assess whether any changes in the factors associated with the desirability of FoCs took place over a five-year period.

Summary of results

The emergence of new technologies along with improved vessel and gear design over recent decades have made it possible for fishing operations to be carried out nearly anywhere. Fishing vessels operate within coastal waters of foreign countries, as well as far out at sea in internationally shared high seas areas where fisheries monitoring, control, and surveillance activities face greater challenges. Along with the expansion of fishing efforts is the expansion of human populations across the globe and an accompanying demand for food from the sea.

Overfishing and the resulting scarcity of local seafood resources have meant that an increasing number of vessels are fishing in distant waters. While our abilities and tendencies to fish farther from shore have increased, our international systems of governance have been playing catch-up to ensure shared resources are exploited sustainably and safely.

Currently, weaknesses in these systems still exist, providing opportunities for rogue operators to gain an economic advantage.

The ability of fishing vessels to register under FoCs is one of these opportunities that, when abused, facilitates IUU fishing—an issue that may not have been anticipated decades ago when relevant international policies were first drafted. FoCs are common throughout the entire maritime sector, and their use is thought to be primarily driven by economic pressures.

Within the global fishing sector there appear to be two different, main reasons for their use: to gain access to fishing areas and resources; and to avoid rules, oversight and costs. These reasons are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and our analysis suggests that they significantly influence flag preference. Desirable flags were found to be of those countries that are largely non-compliant with fisheries-related regulations, regardless of their ratification of major international agreements. The more popularly flown flags are more easily accessible and afford vessels that register under them greater access to more countries’ waters and areas managed by RFMOs. Many of these flags were found to belong to countries that score low on the Human Development Index and some that have undermined international conventions related to transnational organized crime and drug trafficking by not ratifying them.

Some of these same countries have also failed to ratify the major international convention that guides the procedures related to the arrest of ships (which is only possible if both states are party to it) at foreign jurisdictions’ ports.

If a fishing vessel operator has chosen to register under a foreign flag to gain access to fishing areas and resources, this strategy may be perfectly legal and both socially and economically justifiable in theory, though sometimes controversial in practice.

An operator may gain this access by registering their vessel under the flag of the coastal State that has full jurisdiction over the fishing area, often under a ‘joint-venture’ arrangement (discussed below). Alternatively, they may register their vessel under the flag of a country that has a bilateral fisheries access agreement or is party to a regional access agreement negotiated under the auspices of an RFMO.

Our analyses suggest that this is a significant influencing factor in flag choice as the most desirable flags were found to belong to countries that are party to more of these agreements. In order for operations under these arrangements to be sustainable and ethical however, relevant flag States must be capable of, and exercise effective monitoring and control over all vessels flying their flag. In addition, the agreements they are party to must be environmentally sustainable and fair. If a fishing vessel operator has chosen to register under a foreign flag to avoid rules, oversight, and costs, this strategy also may facilitate illegal activity, unregulated activity, or at best unethical, unsustainable, and/or irresponsible activities.

Those that are driven by these incentives are taking advantage of a weak system to the detriment of the likely provide services as FoCs due to continued demand from vessel operators and the fact that registration for these flags produces income.

Further, countries do have differing values and priorities, and not all countries are promoting sustainable fishing to the same degree. Issues of corruption and minimal social consequences may continue to perpetuate their use.

As mentioned, joint-ventures, or other types of private fishing authorizations also represent arrangements where registrations under foreign flags are used to gain access to fishing areas and resources. In joint-ventures, a foreign company partners with a local company or a flag-State government to jointly carry out operations relating to fishing (i.e., research, exploratory fishing, catching, scouting, processing, and marketing). Vessels owned by joint-ventures may be permitted to apply locally for licenses in some countries, and these arrangements may also qualify them to register under a local flag despite being partially or fully owned by foreign entities. In theory, participation in joint-ventures has been defensible as it can be a means for coastal countries that lack capital, infrastructure, markets, and other capabilities, to develop their own industrial fishing industries. However, in practice, major economic issues have emerged, manifesting at its worst when long-term objectives for sustainable exploitation and development are neglected, or when more experienced foreign partners have used financial manipulations to evade a fair sharing of profits or losses. Within the dataset examined, the existence of joint-ventures or other private fishing agreements may explain the popularity of flags that are not known for their ease of accessibility in the maritime domain, and/or are not party to many bilateral or regional fisheries access agreements.

Conclusion

IUU fishing is environmentally destructive, and it also lowers the resilience of marine ecosystems in the face of other major threats to ocean health, such as overfishing, climate change, and ocean acidification. The path towards tackling IUU fishing, however, is relatively uncomplicated compared to the challenge of addressing these other marine conservation issues. Arguably, the ability to reduce IUU fishing to insignificant levels is well within our grasp, and eliminating or restricting the use of FoCs by fishing vessels could accelerate progress towards achieving this.

Significantly reducing IUU fishing will also require a combination of internationally-aligned trade measures, at-sea, port, and market controls. However, initiatives taking this approach need to be thoughtfully implemented with well-enforced measures; otherwise, a new set of loopholes and weaknesses will emerge, and IUU fishing will continue.

Promising economic strategies designed to increase costs or financial risk of involvement in IUU fishing have also emerged within recent years. These efforts have restricted the access that IUU vessels have to services and have mobilized businesses within the seafood supply chain and the global financial sector including, notably, insurance companies.

To suggest banning the use of FoCs across the entire maritime sector as a strategy for combatting IUU fishing is perhaps both unnecessary and unrealistic. The use of FoCs is common amongst shipping vessels, and issues with safety throughout the marine transport industry have been dramatically improved by the establishment of the Paris and Tokyo Memoranda of Understanding and other similar agreements worldwide Within the global fishing sector, however, flag State responsibility—or the lack thereof—appears to be an unaddressed issue leading to the emergence of an FoC market where some of the most desirable flags also facilitate IUU fishing.

Given the known association of FoCs to IUU fishing and the existence of few environmentally, socially or economically defensible reasons to justify their use by the global fishing sector, countries that operate open registers could consider closing these to fishing vessels. In addition, both coastal States and RFMOs could ban the use of FoCs by all fishing vessels authorized to fish within their EEZs and management areas.

All forms of access agreements and lists of authorized vessels should be made publicly available by flag States, coastal States and RFMOs; and countries should maintain a public register of their entire fishing fleet, including foreign-flagged vessels (those registered under FoCs) owned by their nationals. These lists should include information (both current and historical) on vessel flags and beneficial ownership.

All vessels—including those registered under FoCs—should also be monitored by relevant coastal States (if fishing within an EEZ), flag States, and beneficial owner States through vessel tracking (VMS and AIS), wherever in the world they operate.

Governments could also make efforts to stop their nationals from registering the vessels they own and/or operate under FoCs. At a minimum, all countries should have legislation in place preventing their nationals from engaging in, supporting, or otherwise benefiting from the activities of vessels that have been placed on the official IUU vessel list of any RFMO or coastal State.

All of these management measures would facilitate greater accountability through improved transparency; a general strategy that, if broadly applied on a global scale, could significantly improve ocean governance and reduce IUU fishing, making it harder for unscrupulous operators to hide under the cloak of foreign flags.