One of the most read blog posts I have are two called Governance and Tuna Related Institutions in the Pacific part 1 and 2, that I wrote in September 2015. These posts explain the roles of the WCPFC, PNA and the roles of FFA and SPC, as well the place national fisheries administration have in these “system”. I was asked to update it a few times and also describe the Vessel Day Scheme that is run by PNA.

But such task takes time and care, with is exactly what my ex-boss in FFA Mike Batty and my friend and colleague there Viv Fernades have done. I have tons of respect for both, and Mike batty was one of the fist people that trusted me with important jobs in the region decades ago when he was in charge of the DevFISH1 project. I always been very thankful to him for that.

Viv has been with FFA only for a few years, but it has been great to get to know him and work with him, he has very unique background in environmental law and a passion for MCS, hope to keep working with him for along time

In this excellent paper “Management of Tuna Fisheries for Sustainable Development in the Pacific Islands” they explain how the cooperation by Pacific Island countries in the management of tuna fisheries is an important means of achieving sustainable development of these shared resources, in line with Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water). The Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) tuna fishery is the largest tuna fishery in the world and two examples of arrangements based on regional cooperation are provided:

The purse seine Vessel Day Scheme (VDS) is a fisheries management system that is being implemented through the cooperation of the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), which regulates harvesting of tuna in line with SDG 14.4. The scheme also establishes rights in the shared fishery for small island developing states, increasing economic returns in support of SDG 14.7.

Regional cooperation in fisheries Monitoring Control and Surveillance is a unique collaboration between the members of the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) to address illegal, unreported and unregistered (IUU) fishing in support of SDG 14.4. A range of regionally agreed systems and tools is applied.

I will quote the description of the institutional arrangements (from the intro of the paper as an update of “who does what” in the Pacific) and the discussion and conclusions. But I said every time, nothing beat the original, in particular the excellent description of the two examples with very good evaluation of their successes… this paper a compulsory read if you interested in Pacific tuna fisheries

I know the paper is paywall protected, yet with a bit of initiative and know who to ask or which websites to use you can get them for free (Personally I don’t have the budget to be subscribed to them, so I improvise and normally ask authors for the paper)

Institutional Arrangements for International Cooperation in the Fishery

Tropical tuna and associated species are highly migratory, and the stocks ex-tend throughout the Pacific Islands’ EEZs and beyond. This shared nature of the fishery, the limited scientific and technical resources of the Pacific Island Countries, and the common issues faced in managing and developing their fisheries, has resulted in the establishment of a number of regional organisations to assist countries to cooperate in the management and development of the resource. The main regional organisations, in order of increasing geo-graphical extent, are the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), the Pacific Community (SPC), and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). An overview of each, including their roles and objectives, is provided below.

The PNA are the eight countries whose EEZ’s contain the majority of the WCPO purse seine fishing grounds: Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Republic of the Marshall Islands, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu. Established in 1982 as a group that faced common issues in their relations with distant water fishing nations (DWFN), the PNA implement two mutually agreed arrangements. The Federated States of Micronesia Arrangement (FSM Arrangement) is intended to support the development of domestic tuna industries and provides for vessels of a member country that meet certain criteria to have access to the EEZs of all other parties on terms no less advantageous to those provided to vessels of other countries. The Palau Arrangement provides for management of the tropical tuna fishery. In the case of the purse seine fishery, this was originally managed through an agreed limit on the total number of vessels, but has since been replaced by the purse seine VDS, which is discussed below. The New Zealand Territory of Tokelau, although not a member of the PNA, is a party to the Palau Arrangement.

There are also three implementing arrangements (IA) which provide a framework for compliance that are incorporated into national legislation or licence condition. These cover minimum terms and conditions of licencing and include: a requirement to carry observers on board purse seine vessels, requirements for vessels to be on good standing on a shared register of vessels, reporting and inspection requirements (the first IA); mandatory position reporting through a satellite based vessel monitoring system (VMS), reporting of activities port-to port (i.e. including on the high seas) and a prohibition on transhipment at sea (the second IA); as well as a prohibition on the use of Fish Aggregation Devices (FADs) for part of the year, and a ban on the discard of tuna. Many of these requirements have also been adopted by the broader FFA membership.

FFA is an international organisation established under the FFA Convention in 1979. Its formation was directed by the leaders of the Pacific Forum, who recognised the need for a specialist agency to advise on the establishment and management of 200 nautical mile EEZs during the later stages of the negotiation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Members include all of the PNA members, as well as Australia, Cook Islands, Fiji, New Zealand, Niue, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu; as well as Tokelau (the only member that is not an independent country). For the non-PNA members, their main fishery is the Southern longline fishery which mainly targets albacore. FFA provides a range of advisory services to its Pacific Island member countries on all aspects of tuna fisheries management and development, assists members develop a common position in the WCPFC and also manages the regional fisheries surveillance programme, discussed below.

SPC, formerly the Secretariat of the Pacific Community was established more than 70 years ago by the colonial powers in the region. Its membership includes the independent Pacific Island countries, the territories of France, Great Britain, New Zealand and the United States of America, as well as Australia, France, New Zealand and USA in their own right. SPC provides technical services to members in a range of areas. Its Oceanic Fisheries Programme is particularly relevant to the tuna fishery. This programme has conducted applied research and stock assessments of the regional tuna resources for many years and is the shared repository of all operational fisheries data for its members. SPC works directly with members, as well as with FFA and PNA, to meet members’ needs in the area of tuna fisheries science. It is also the scientific services provider for the WCPFC.

The WCPFC is a tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organisation (t-RFMO) established in accordance with the United Nations Agreement for the Implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 0 December 1982 relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (un Fish Stocks Agreement). It is governed under a convention, which was ratified by most members in 2004. In addition to the FFA member countries, which worked as a bloc during the negotiation of the convention and comprise one of the two voting chambers, the WCPFC membership includes Indonesia and Canada, as well as the DWFN active in the Pacific region: China, Chinese Taipei, France, European Union, Japan, Republic of Korea, Philippines and the United States of America, some of whom are also coastal States in the convention area. The extent of the WCPFC convention area mainly corresponds to FAO area 71.11 Boundaries are to the south of New Zealand in the South and enclose the EEZ of French Polynesia in the East, and while not precisely defined to the North and West, are considered to enclose part of the EEZ of Indonesia and extend up to the waters of Japan and Korea.

Discussion and Conclusions

The implementation of purse seine VDS and cooperative arrangements for MCS in the Pacific have been shown to contribute to efforts to effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (SDG 14.4) and increase the economic benefits to SIDs and Least Developed Countries in the region (14.7). The VDS has effectively capped fishing effort in what is by far the largest tuna fishery in the region, and halted some thirty years’ of growth in catches in PNA waters. None four of the main tuna stocks in the region are overfished or subject to overfishing. Since the scheme was introduced, government revenues from access fees have quadrupled, and the number of domestic fishing vessels and their share of the catch (in a fishery that has always been dominated by foreign fleets) has increased.

These cooperative approaches are tangible examples of how the Pacific Is-land countries are successfully moving towards achievement of these SDGs through progressive improvements in management of the purse seine fishery for tuna in their EEZs, and a growing ability to enforce the management regime through MCS. Regional cooperation between these small and economically vulnerable nations has been essential in achieving these gains.

The VDS has also illustrated that two goals of sustainable management and increased revenues are compatible. Just as SDG 14.6 argues for the elimination of subsidies which allow fishing to continue on depleted stocks, so the ability to charge high access fees (the opposite of a subsidy) is helping to ensure that stocks are maintained at levels which allow a profitable fishery. Indeed, it is likely that the recent decline in fishing effort recorded reflects the economic impact of high access fees. The number of purse seiners operating in PNA waters has fallen from around 275 from 2010–15 to only 259 in 2016 and 2017 as less efficient vessels have withdrawn from the fishery.

This final section aims to draw some general lessons from the experience of the Pacific Island countries with the implementation of the zone based management regime of the VDS and cooperative MCS strategies; consider to what extent it may be possible to replicate their success in other parts of the world; and review some threats and opportunities for the future.

The development of the VDS and regional cooperation in MCS has not been quick or easy. Both the PNA and the FFA have been in existence for nearly four decades, and each agreement to take a major step forward has required consultation to develop consensus, and follow-up at the national level for implementation and capacity building.

The success of the purse seine VDS reflects some unique characteristics of the WCPO fishery. The extent of the PNA EEZs and their importance as fishing grounds for the purse seine fleet gives the member countries considerable leverage and is in contrast to other oceans where much of the tuna fishing takes place on the high seas. The diversity of interests in the fishery allows for competition for the limited opportunities for access, while its economic profit-ability has allowed a large increase in fees.

In contrast, efforts by PNA members to develop a tropical longline VDS – for a fishery that is less profitable and is practiced mainly on the high seas – have been less successful to date. Opposition by some of the major distant water fleets has seen many vessels restrict their operations to the high seas. FFA members whose waters provide most of the catches of albacore have committed to the Tokelau arrangement, which aims to introduce zone based management to this important, albeit smaller, fishery. However, reaching agreement on a catch management scheme has proved challenging; while proposals by FFA members to introduce a target reference point in WCPFC that would lead to reduced catches and improve the profitability of the fishery have also not been accepted. Longline fisheries remain an area for further work.

The principle of zone-based rights established by the purse seine VDS – that allocation of fishing opportunities in a shared fishery should reflect the interests of the coastal States in whose waters fishing takes place – is an important one. It has found support from coastal States in the Indian Ocean, and has even been proposed as a basis for a new allocation of fishing quotas to Great Britain after Brexit. As shared tuna fisheries face growing pressure, and the need to limit catches or effort, one can expect the development of a strong view that the allocation process should not exclusively favour the distant water flag States. These fleets have already benefited from many years of access to the resource, and been responsible for the depletion of stocks to date.

Looking to the future, there would seem to be opportunities to further increase returns from the VDS. There are inefficiencies in the transferability of days between zones; and current practices of negotiating access arrangements for an entire national fleet mean that fees may be set at the level that is affordable by less efficient components of the fleet. There is also a risk that the least profitable vessels will continue to withdraw from the fishery, resulting in reduced competition for fishing opportunities. Ideally, days would be sold to individual vessels through a system such as a Dutch auction, which could match fee levels with ability to pay and ensure all days are sold efficiently.

The VDS has contributed to the growth in Pacific Island national fleets, which are taking a growing share of the purse seine catch. While the development of domestic fisheries, as opposed to simply licensing foreign vessels, is a long-held ambition of many Pacific SIDS, there are also both threats and opportunities in these arrangements. In the best circumstances, these provide employment, economic opportunities for a range of supporting industries, and supply tuna to onshore processing plants which create jobs and exports. At worst, they may amount to little more than re-flagging to secure lower access fees, and actually reduce the contribution of the sector to gross national income. The capacity to analyse the economic benefits of such arrangements is not always present in Pacific Island administrations, where the governance arrangements around concessions for domestic vessels can also be weak.

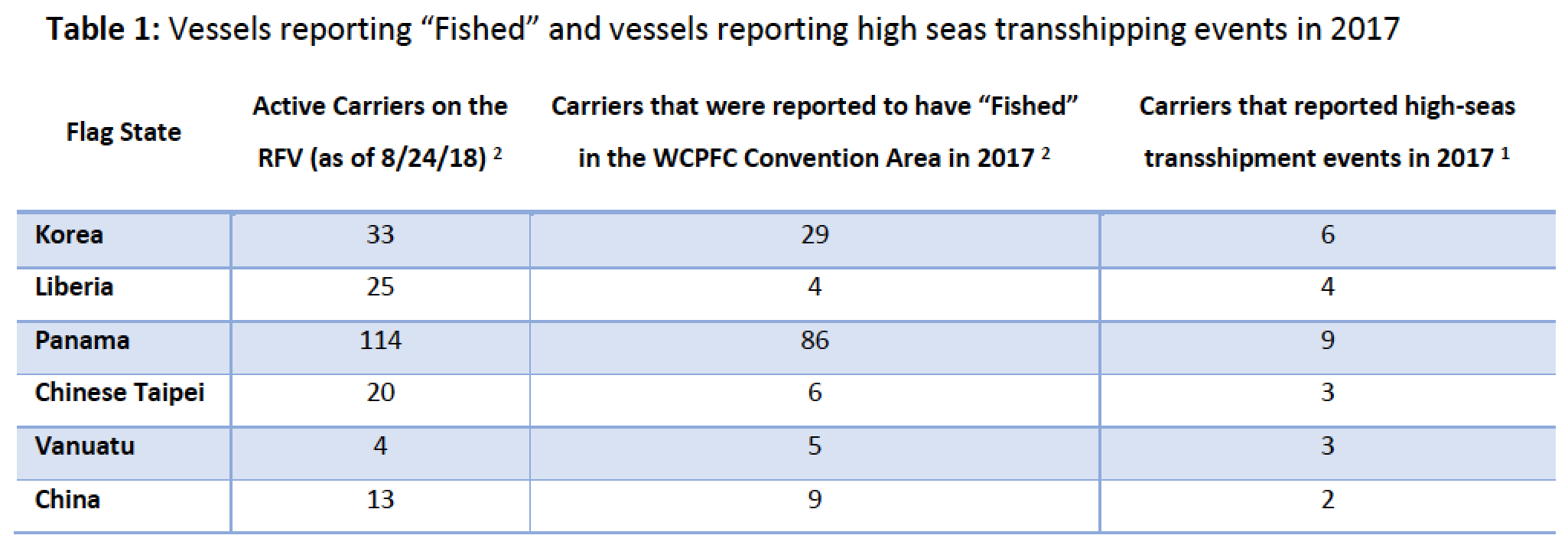

Higher access fees, and restricted fishing opportunities in EEZs, also create incentives to avoid payment, either through fishing on the high seas or by fishing illegally. Since the introduction of the VDS, three fishing nations have negotiated increased opportunities to fish on the high seas through the WCPFC. Together with the high seas effort of Pacific Island flag vessels, there has been a steady growth in purse seine catches outside PNA waters since 2011.

While there is so far little evidence of increased illegal fishing, the validation of non fishing days is a potential area of abuse; and can be expected to result in increased pressure on fisheries observers. There is currently interest in detecting purse seine fishing activity from the VMS record, as well as the possibility of supplementing human observers with electronic monitoring through on-board video recording.

While it is believed that no other regions share the level of international cooperation on MCS seen in the Pacific, the transnational nature of much IUU fishing is driving a more coordinated international response to the problem in other parts of the world.

There are now arrangements to share information and coordinate efforts between coastal states in West Africa and the Indian Ocean; and market based measures such as the EU IUU regulation and the EU Seafood Import Monitoring Programme may also assist in combating the problem.

While FFA members can have confidence in regional MCS systems for the tuna fishery, it is clear that the region is still a long way from the SDG goal of eliminating IUU fishing. Quantification of the relative importance of unreported catches necessitates more attention to this area, with opportunities for greatly increased use of electronic reporting and monitoring in the fishery. At the same time, the relatively low level of unlicensed fishing cannot be taken for granted, and systems to identify ‘dark targets’ using increased aerial surveillance and satellite imagery, remain a priority for FFGA.

In conclusion, while much remains to be done, the achievements of Pacific SIDS through cooperation in the management and sustainable development of their shared tuna resources gives grounds for optimism, and can perhaps provide some useful ideas for other regions.