There have been plenty of talk in the media and tuna world of the “sinking of the US treaty” last week, and I been asked about my views on it. So I here is my take on this, with a big acknowledgement to Chris Lord who put together his views and let me quote him here. The man has been in the Tuna business for a long time and is well read on the issues.

The fact

The United States has given Pacific Island nations notice that it plans to withdraw from the South Pacific Tuna Treaty, one of its most important aid, trade and geopolitical arrangements with the region. The 27-year-old treaty is set to expire 12 months from the date of the withdrawal notice. The announcement came after Washington agreed in South Pacific Tuna Treaty negotiations in August, to a total of $89.2 million for 2016 fishing days, but within months reneged on the deal saying its fleet could not afford to pay.

What is the Tuna treaty?

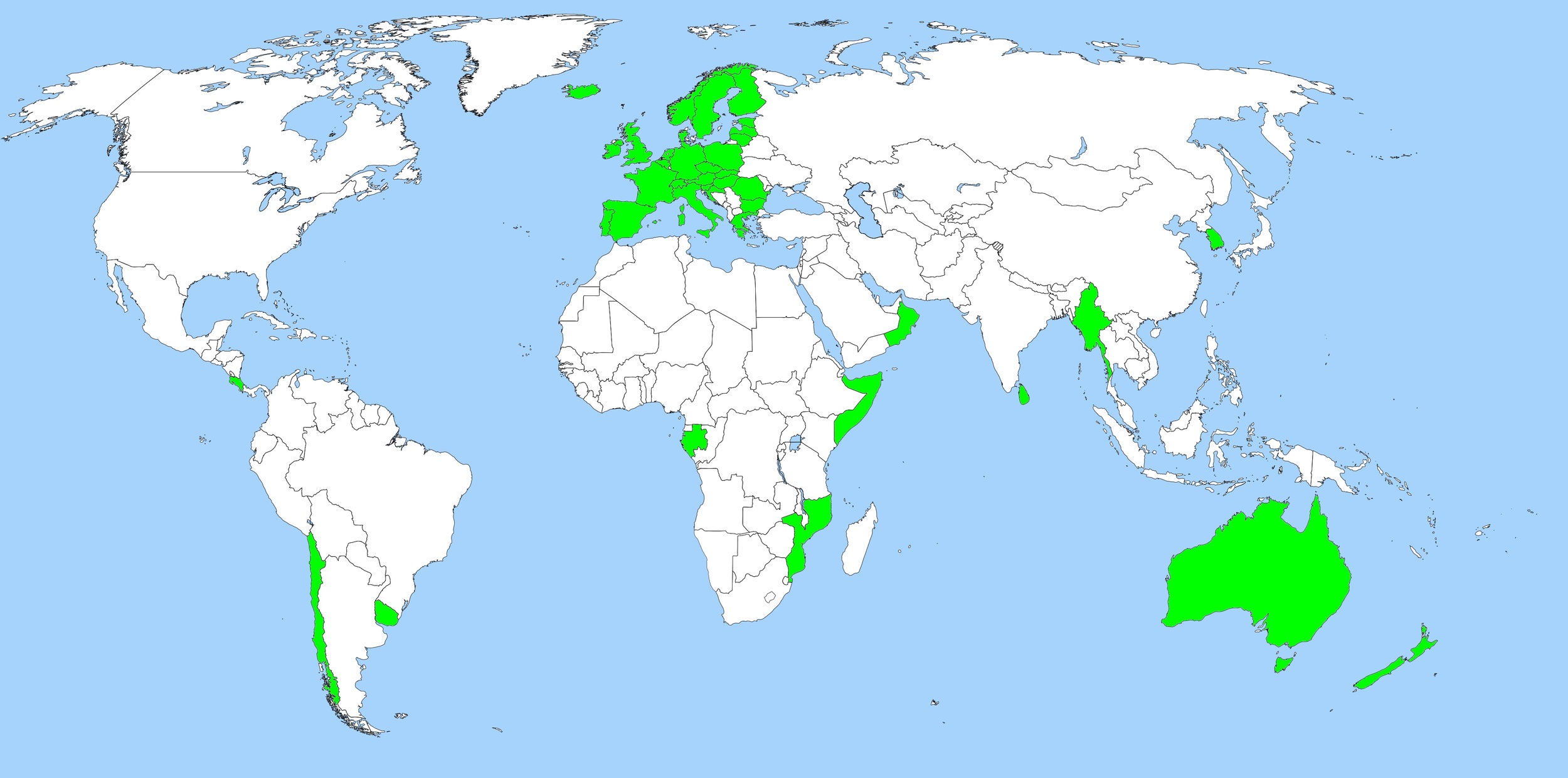

The Multilateral Treaty on Fisheries Between Certain Governments of the Pacific Island States and the Government of the United States of America (commonly known as the “US Treaty”) began in 1987. It entered into force in 1988 and has since been renewed twice, with the last renewal in 2003 allowing the US Treaty to continue for an additional 10 years until 2013. The treaty enables a maximum of 40 US purse seine vessels to fish in the waters of the 16 Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) member states. From the 16 countries, Australia and New Zealand do not receive any development aid from the treaty. In exchange for fishing access the US contributes an agreed annual amount, regardless of how much fish they take out. Under this arrangement the USA has, in the first 16 years of operation, paid the FFA a total of US$276 million. Once the administration fee is put aside, the FFA then divides these funds in two parts. First, each Pacific Island party receives a fixed minimum payment and the other part (a major component) is based on the amount of tuna caught in national waters of each member states. In effect almost 80% of the money has been diverted to five countries (Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Nauru, Papua New Guinea and Tuvalu – all PNA countries) based on the distribution of skipjack stock in the region.

Last week, The United States government has officially announced it is pulling out of the US Pacific islands fisheries treaty. The US State Department this week advised the Forum Fisheries Agency that it had officially communicated to the Papua New Guinea government - which is the depository for the treaty - that it is withdrawing from the treaty. The State Department's move was presaged last month when the US government and its tuna fishing industry asked the FFA to "take back" 2,000 fishing days that the American fleet had requested as part of an earlier package of over 6,000 vessel days for 2016. FFA refused, saying it was a signed agreement that the US should abide by. Hence it (FFA) refuses to issue new licences until the U.S. pays for all 5700 fishing days agreed during the Tuna Treaty negotiations in Brisbane during August 2015 (I wrote about it here), a total of $89.2 million, and the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has decreed that, as of 01 January 2016, all 37 purse seiners in the U.S. tuna fishing fleet are prohibited from fishing in the western Pacific region until new licences are issued.

This dispute, of course, has a bigger framework that what is only seen at the surface... it seems (as Chris coined it) the culmination of the “perfect storm”: supply, demand, fishing access and weather.

Supply

A price crisis is hitting the purse seine tuna fishing industry in the central and western Pacific. In fact, tuna landings on both sides of the Pacific have been at record levels for most of the year. Fishing vessels and island-based processors are losing money as a glut of tuna on the market keeps prices low. The western and central Pacific account for half of the global supply of skipjack tuna, and the price of skipjack on the world market has plummeted, from over US$2000 per ton in 2013, to less than US$1000 today. In these circumstances, all US vessels have been losing money, according to the American Tunaboat Association.

In April, the World Tuna Purse Seine Organization (WTPO) announced a 35% reduction in fishing effort until the end of the year, in an effort to pull the industry out of the market crisis. The measure covered the Western and Central Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and applied to all commercial refrigerated industrial tuna purse seiners. Fleets in the Eastern Pacific Ocean were excluded from the measure due to the upcoming fishery closure in the region in Jul-Aug.

The slow-down in operations implemented by the WTPO temporarily lifted prices, but they quickly fell again when catch rates were not significantly decreased.

In Ecuador, annual closures to fishing activity also failed to reduce landings. As a result, cold stores filled and refrigerated carrier vessels were backed-up in regional transshipment ports. Processors in Southeast Asia have been operating below capacity, with many factories in Ecuador reduced to a single-shift basis. Catch rates remained high through the end of the year. This is reflected in current offers of skipjack tuna at $950 per ton for January deliveries to Bangkok.

In short, vessel operators have been losing money.

Demand

Global demand for shelf-stable tuna products has been in a slump for at least the past two years. As the supply increased, prices fell and buyers become reticent to commit forward. It boils downs to a classic case of “supply vs. demand” economics… too much fish and slow sales of finished products.

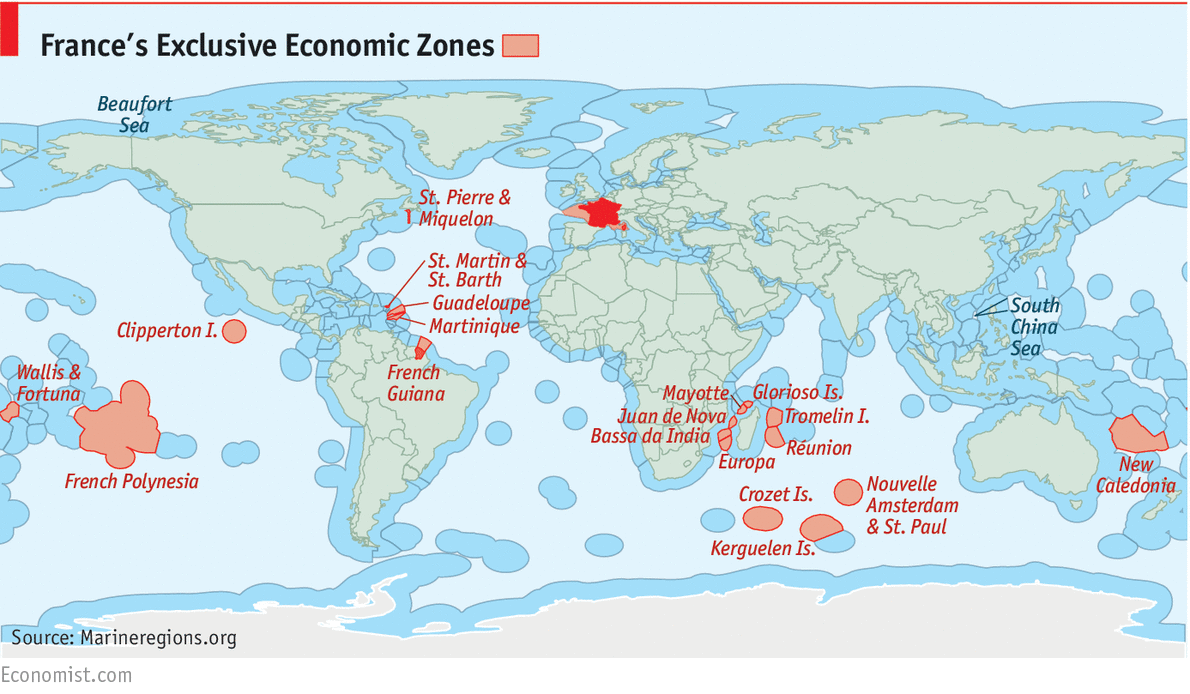

Another factor in the slump is a growing consumer trend away from canned foods towards, fresh and natural products. Consumption levels in traditional markets such as Europe and the US, are stable or declining. Asia-Pacific processors depend heavily upon these markets for canned tuna and pre-cooked loin exports. In addition, access to these markets, especially the EU, has become increasingly complex.

Future growth in canned tuna demand will likely stem from emerging markets. However, the largest of these, the Middle East, has been severely disrupted by political turmoil, in particular, Egypt and Libya. This makes for stiff competition in other emerging markets, such as Latin America.

Finally, the industry’s propensity for “shooting itself in the foot” has also played a role in eroding consumer confidence. A seemingly never-ending series of events involving major players in the industry have made the headlines. These fall into three (3) basic categories:

- Social welfare: Human trafficking, slavery and forced labor

- Responsible fishing: IUU fishing, traceability and sustainability (FADs)

- Ethical business practices: Under-filling, price-fixing, truth in labeling (Omega-3)

Following are some examples…

- In 2013, a class-action suit was filed accusing StarKist of “systematically under filling and selling short weighted cans of StarKist Chunk Light Tuna in Water”, a violation of California’s consumer laws, amounting to “negligent misrepresentation”, “unjust enrichment” and “fraud”.

- About the same time, StarKist’s Korean mother company, Dongwon Industries, came under fire for the mutiny of an American purse seine captain, as well as appalling working conditions, illegal fishing practices, and deceit over tuna fishing licences, all in relation to its purse seine vessel, “Majestic Blue” . The Company later re-flagged the vessel and withdrew from the South Pacific Tuna Treaty as a vessel-owner.

- The recent disappearance of Keith Davis , a US Fisheries Observer from a Panamanian flagged tuna carrier. Unfortunately one in a list of observers’ deaths I wrote about it before

- In April 2015, the European Commission issued a 'yellow card' to Thailand (where most of the tuna in the world is processed) for not taking sufficient measures in the international fight against illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU). A somewhat belated response from the government is addressing the issues. Only time will tell if the EU deems the response to be sufficient.

- In June 2014, Thailand was downgraded to the lowest ranking (Tier 3) on The US State Department Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report, joining al illustrious list of countries, including Iran, North Korea, Libya, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. In July 2015, this status was reconfirmed for a second year.

- A shocking report by the Associated Press (AP) documented a year-long investigation of a single large shipment of slave-caught seafood from the Indonesian village of Benjina, to Thai ports, thru most major Thai seafood processing plants and onto familiar retailers in the United States. This report sparked government action in Thailand and Indonesia that has at least taken steps towards resolving the matter. Sadly, the leader of Thailand's investigation team into Rohingya human trafficking was reassigned to the very area where he conducted the investigations. His pleas to his superiors for reconsideration fell on deaf ears. Fearing retribution from "senior police involved with the trade”, he was forced to flee to Australia, where he is now seeking political asylum.

- Recently Greenpeace ranked fourteen US tuna brands regarding “fundamental sustainability standards”, which to Greenpeace, means fishing with Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs). The top three US canned tuna brands: Bumble Bee, Chicken of the Sea and StarKist all failed and occupied three of the bottom four positions. A similar ranking in the UK later in the year, ranked Thai Union’s John West brand last out of eleven brands. To drive the point home, Greenpeace followed up with highly publicized protests in San Diego and Liverpool, at the headquarters for Thai Union owned Chicken of the Sea and John West brands respectively.

- The U.S Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division announced it is conducting an investigation into price collusion in the Packaged Seafood Industry. Forty-three (43) class-action suits from various states, directed primarily at Chicken of the Sea, Bumble Bee Foods and StarKist, followed and have now been consolidated in California. This series of events more or less scuttled Thai Union’s proposed take-over of Bumble Bee.

- Late in the year, Bumble Bee was also hit with class-action suits regarding improper Omega 3 labeling of tuna and other seafood products. The suit claims Bumble Bee had no legal right to claim the products as an “excellent source of Omega-3s”, as the required applications had not been submitted to US FDA.

Considering the above issues, and growing consumer interest in sustainability, transparency and social welfare, it is logic to see lower consumption (even if not all players are tainted) .

Fishing Access

A major mitigating factor to this dispute was Kiribati's sovereign decision in October 2014 at the Honolulu negotiations, when they announced that due to “other commitments”, they would allocate only 300 fish days towards the treaty with the US in 2015, a 95% reduction, as compared to 4313 days in 2014.

Whatever the reasons, the number of VDS days Kiribati allocated to the Treaty was not sufficient for the US fleet to be able to operate economically within their EEZ. Neighboring Pacific countries to Kiribati offered fishing days to replace those the US had lost but, they were not feasible options.

Kiribati's EEZ (exclusive economic zone) is closest in proximity, only two to three days away from the tuna processing factories in American Samoa. Fishing grounds in Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands or Micronesia are as long as 10 to 12 days away. It is simply not economical for those boats to go such a distance to fish and then turn around and come back all the way to American Samoa. It would be far more practical to transship the fish onto carriers supplying fish to Southeast Asia.

In short, the net effect of this move by Kiribati was to diminish the value of the entire Treaty to the US fleet.

Weather

To make matters worse, the strong El Nino effect during 2015 pushed tuna fishing away from Papua New Guinea towards Kiribati, exactly where the US fleet had limited access. In June, SPC said “stocks will likely move towards the exclusive economic zones of Kiribati, Tuvalu, Tokelau and Nauru. “As water temperatures change, we should see very strong fishing activity and catches towards the central Pacific side of the region”. He also said, “If this event impacts the biology of the tuna resource in a similar fashion as it has in the past, we should see a fairly strong recruitment particularly for Skipjack tuna for the next year”, suggesting that the high catches being experienced will continue. He also offered this opinion, “while that's good from a catching perspective, there is concern the current depressed price of skipjack tuna in the marketplace will not be assisted by continuing strong supply”.

In light of all the above, it is not difficult to understand why the US pushed so hard at South Pacific Tuna Treaty negotiations in August 2015, in Brisbane, Australia, to increase the number of fishing days, only to declare less than three months later that the US fleet could not afford to pay for them.

I love to hear if anyone out there, that has diverging opinions on Chris take on this, as it is an important for tuna fishing in the Pacific.