Figure 4: Reconstructed global catch by fisheries sectors.

Also noticeable is that the inter-annual variations (small peaks and troughs) in both reconstructed catches and reported catches (Fig. 1) are mainly driven by industrial data, which are relatively well documented and reported in time series, while the small-scale sector data are smoother over time (Fig. 4), and more strongly influenced by continuity assumptions over time as part of the national reconstructions.

While some countries increasingly include subsets of artisanal catches in official catch statistics provided to FAO, subsistence fisheries catches (Fig. 4) rarely are10. Worldwide, subsistence fisheries caught an estimated 3.8 mt·per year between 2000 and 2010 (Fig. 4). The current global estimate of just under 1 mt·per year of recreational catches is rather imprecise, and recreational fishing is declining in developed, but increasing in developing countries.

Discarded bycatch, generated mainly by industrial fishing, notably shrimp trawling22, was estimated at 27 mt·per year (±10 mt) and 7 mt·per year (±0.7 mt) in global studies conducted for FAO in the early 1990s and 2000s, respectively. However, these point estimates were not incorporated into FAO’s global ‘capture’ database, which thus consists only of landings. Here, these studies are used, along with numerous other sources, to generate time series of discards (Fig. 4). Discards, after peaking in the late 1980s, have declined, and during 2000–2010, an average of 10.3 mt·per year of fish were discarded.

Discussion

Our reconstructed catch data, which combines the data reported to FAO with estimates of unreported catches (that is, reconstructed data are ‘reported FAO data+unreported catches’) include estimates of uncertainty (Fig. 1) associated with each national reconstruction. Note that many reconstructions are associated with high uncertainty, especially for earlier decades, for sectors such as subsistence which receive less data collection attention by governments, and for small countries or territories (Fig. 1). We include uncertainty estimates here, despite the fact that reconstructions address an inherent negative bias in global catch data (that is, address the ‘accuracy’ of data) and not the replicability of catch data collection (that is, the statistical ‘precision’ of such estimates), which is what ‘uncertainty’ estimates (for example, confidence limits) generally are used for. We do recognize that any estimates of unreported catches implies a certain degree of uncertainty, but so do officially reported data. Most countries in the world use sampling schemes, estimations and raising factors to derive their national catch data they officially report domestically and internationally, all without including estimates of the uncertainty inherent in the numbers being reported as official national catches.

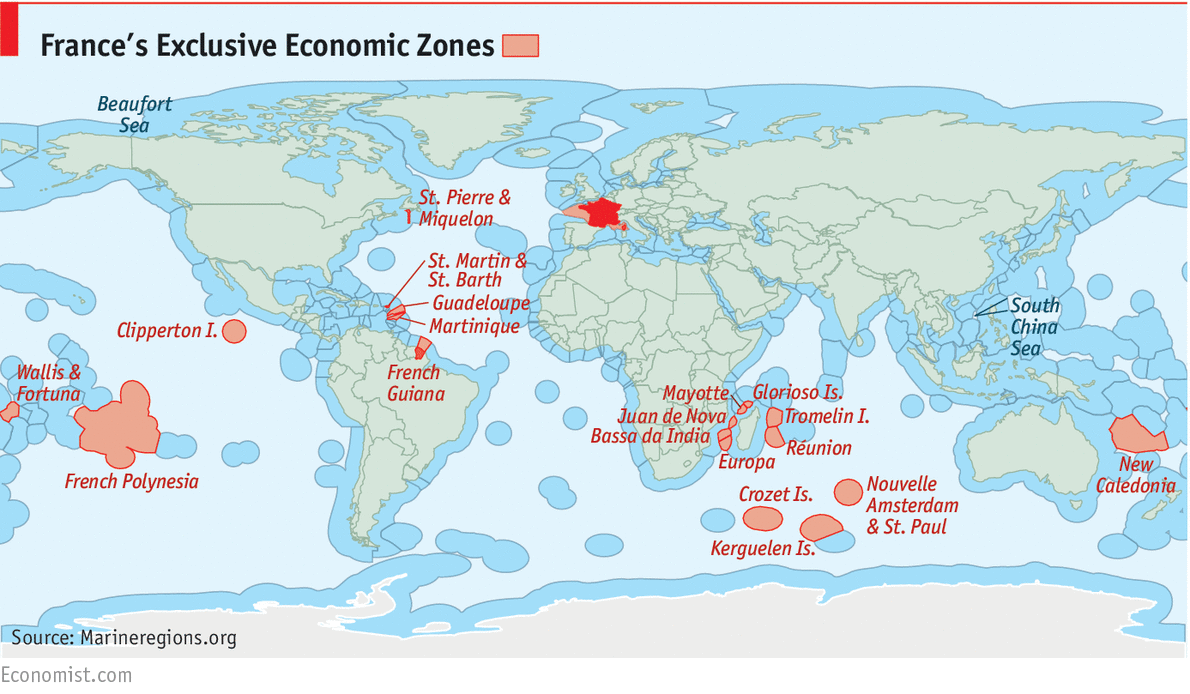

Our comparison of the reconstructed versus reported catches in each of the 19 maritime FAO statistical areas suggests that some of the lower-latitude areas still appear to have increasing reported catches. This generally increasing trend is most pronounced in the Indian and Western Central Pacific Oceans (Fig. 3), where the reconstructed catches are most uncertain, as the statistics of various countries could only partially correct a regional tendency to exaggerate reported catches5. FAO’s Indian and Western Central Pacific Oceans areas are also the only ones with an increasing FAO reported catch, which, when added to that of other FAO areas, makes the FAO reported world catch appear more stable than it is based on our global reconstructions.

Our data and analyses show that, at the global scale, it is a declining industrial catch (plus a smaller contribution of gradually declining discards) that provide for the declining global catches, while artisanal fishing continues to show slight growth in catches (Fig. 4). Thus, the gradually increasing incorporation of artisanal and other small-scale catches in the officially reported data presented by FAO on behalf of countries is partly masking the decline in industrial catches at the global level. Since officially reported data are not (at the international level) separated into large-scale versus small-scale sectors, this trend could not be easily documented until now. Obviously, these patterns may vary between countries. Furthermore, while parts of artisanal catches are increasingly included in official catch statistics by some countries, non-commercial subsistence fisheries catches, a substantial fraction of it through gleaning by women in coastal ecosystems such as coral reef flats and estuaries are generally neglected. The importance of subsistence fishing for the food security of developing countries, particularly in the tropical Indo-Pacific, cannot be overemphasized.

Our preliminary and somewhat imprecise reconstruction of recreational catches indicates that this sector is largely missing from official reported data, despite FAO’s annual data requests explicitly allowing inclusion of recreational catch data. This activity, however, generates an estimated 40 billion USD·per year of global benefits, involves between 55 and 60 million persons, and generates about one million jobs worldwide.

Finally, our country-by-country reconstructed data supports previous studies illustrating that global discards have decreased12, 24. Discarded catches should therefore be included in catch databases, if only to allow for correct inferences on the state of the fisheries involved in this problematic practice.

The reconstructed catch data presented here for the first time for all countries in the world can contribute to formulating better policies for governing the world’s marine fisheries, with a first step being the recognition in national policies of the likely magnitude of fisheries not properly captured in the official national data collection systems.

This recognition will hopefully contribute to improvements in national data collection systems, an aspiration that we share with FAO. For example, in Mauritania and Guinea Bissau, which, in large part as a result of the reconstructions and our ongoing direct engagement with these countries, are now initiating national data collection systems for recreational fisheries (a growth industry in both countries and missing from current data systems). It is hoped that this type of data, and other missing data (for example, subsistence catches), will be included in future national data reports to FAO, as is the case for some other countries such as Finland.

The taxonomic composition of this reconstructed catch (not presented here but available from the Sea Around Us and through the individual catch reconstruction reports) can also contribute to the development of more useful first-order indicators of fisheries status than has been possible previously, especially in the absence of comprehensive stock assessments for all taxa targeted.

A policy change that would be straightforward for FAO to coordinate and implement with all countries around the world is to request countries to submit their annual catch statistics separately for large-scale and small-scale fisheries, which would be an excellent contribution towards the implementation of the ‘Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication’ recently adopted and endorsed at the thirty-first Session of the FAO Committee on Fisheries and Aquaculture (COFI) in June 2014 (ref. 35). While we have found that many countries already have such data or data structure at hand, until all countries can implement such a data-change request, FAO could incorporate such a split into their internal data harmonization procedures, based, for example, on the same or similar information sources as used by the reconstructions.

The very high catches that were achieved globally in the 1990s were probably not sustainable. However, they do suggest that stock rebuilding, as successfully achieved in many Australian and US fisheries, and beginning to be applied in some European fisheries, is a policy that needs wider implementation, and which would generate even higher sustained benefits than previously estimated from reported catches.

On the other hand, the recent catch decline documented here is of considerable concern in its implication for food security, as evidenced by the decline in per capita seafood availability (Fig. 2). Note that the recent, strong decline in reconstructed total catches is also evident if catches in countries with well-established quota management systems (United States, Northwestern Europe, Australia and New Zealand) are excluded (Fig. 2).

Low quotas are generally not imposed when a stock is abundant; rather low and reduced quotas in fully developed fisheries are generally a management intervention to reduce fishing pressure as a result of past overfishing. Similarly, it has been proposed that strongly declining catches in unmanaged, heavily exploited fisheries are likely a sign of overfishing. The often raised suggestion that aquaculture production can replace or compensate for the shortfall in wild capture seafood availability, while being questionable for various reasons, is not addressed here.

The last policy relevant point to be made here transcends fisheries in that it deals with the accuracy of the data used by the international community for its decision making, and the generation of factual knowledge that this requires. After the creation of the United Nations and its technical organizations, including the FAO, a major project of ‘quantifying the world’ began to provide data for national and international agencies on which they could base their policies. As a result, large databases, for example on agricultural crops and forest cover, were created whose accuracy is becoming increasingly important given the expanding exploitation of our natural ecosystems.

Periodic validation of these databases should therefore be a priority to ensure they avoid producing ‘poor numbers’. For example, reports of member countries to FAO about their forest cover, when aggregated at the global level, suggest that the annual rate of forest loss between 1990/2000 and 2001/2005 was nearly halved, while the actual loss rate doubled when assessed by remote sensing and rigorous sampling. Similarly, here we show that the main trend of the world marine fisheries catches is not one of ‘stability’ as cautiously suggested earlier by FAO, but one of decline. Moreover, this decline, which began in the mid-1990s, started from a considerably higher peak catch than suggested by the aggregate statistics supplied by FAO members, implying that we have more to lose if this decline continues. Thankfully, this also means that there may be more to gain by rebuilding stocks.

For the global community, a solution could therefore be to provide the FAO the required funds to more intensively assist member countries in submitting better and more comprehensive fishery statistics, especially statistics that cover all fisheries components, and report data by sector. Such improved statistics can then lead to better-informed policy changes for rebuilding stocks and maintaining (sea)food security. Alternatively, or in addition, FAO could team up with other groups (as was done for forestry statistics) to improve the fisheries statistics of member countries that often have fisheries departments with very limited human and financial resources.

Ultimately, the only database of international fisheries statistics that the world has (through FAO) can be improved. The more rapid decline of fisheries catches documented here is a good reason for this.